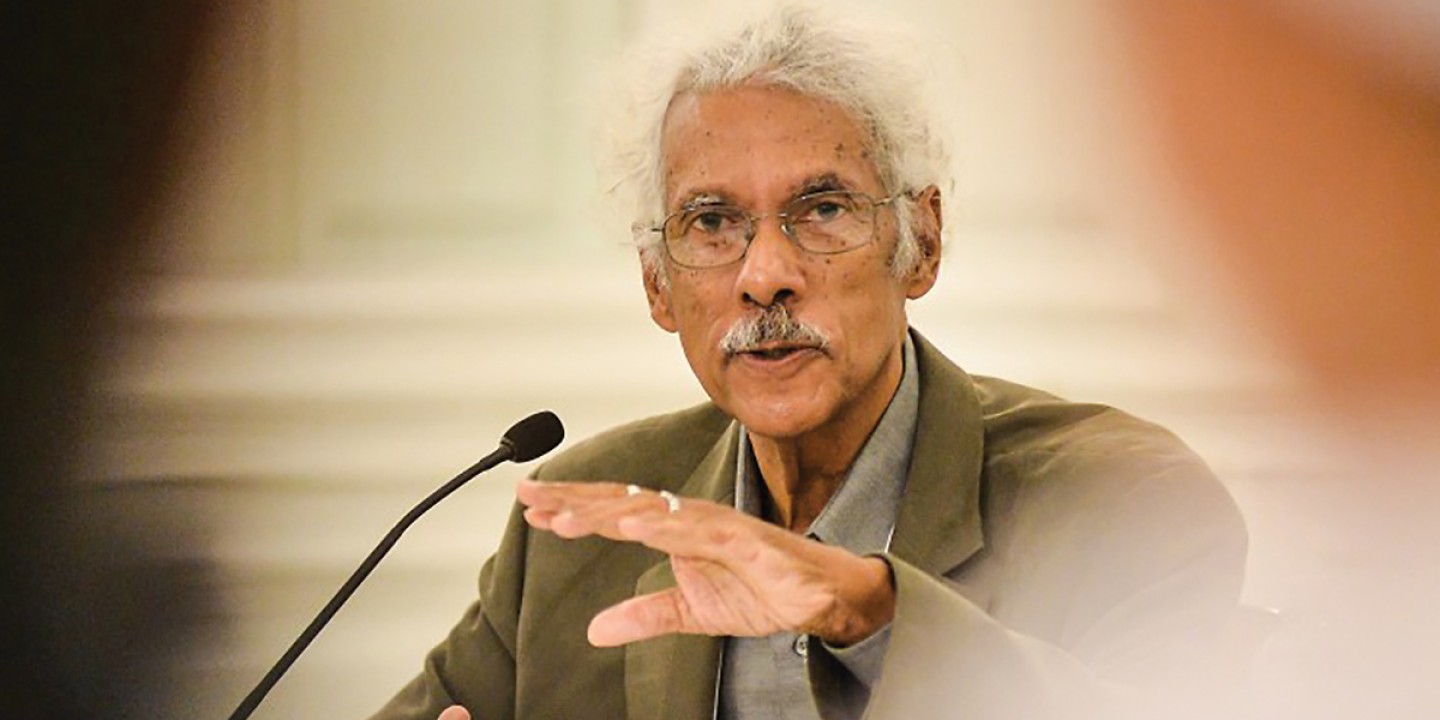

Albert J. Raboteau changed both American religious studies and African American studies

He was among the first to ask, What is religion for a people birthed in the cradle of chattel slavery?

Albert Raboteau’s meeting with me in 2007 was out of professional obligation. As I explained in the email I sent a week earlier, I had recently moved back to Princeton to take a faculty position, and I was a former undergraduate student of his. Could we please meet for coffee? With his trademark kindness, Dr. Raboteau agreed to meet, although I was sure he did not remember me, given the number of undergraduate students most college professors teach over a lifetime. You get to know your doctoral students, those you are guiding into the profession, those you plan to welcome as colleagues after a long apprenticeship. But undergraduates come and go swiftly, most of them an indistinguishable mass of names and faces.

At the coffee shop, the first thing he said to me was, “Call me Al.” But that was one thing I could never do—not even when I received news of his death last month, and not even as I remember with these few words the impact he had on generations of students. He will forever be my teacher.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Like most people, I knew Raboteau as a consummate scholar and critical thinker, the Henry W. Putnam Professor of Religion at Princeton University. The bulk of his academic work was written before I began my career, so it was as a student that I was introduced to his groundbreaking book Slave Religion: The “Invisible Institution” in the Antebellum South (1978), to A Fire in the Bones: Reflections on African-American Religious History (1995) and Canaan Land: A Religious History of African Americans (1999), and to his personal memoir A Sorrowful Joy (2002). Among his many other publications were the co-edited volumes African-American Religion: Interpretive Essays in History and Culture (1997) and Immigration and Religion in America: Comparative and Historical Perspectives (2009).

At the time of our 2007 meeting, he was working on his final book, American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals and Their Struggle for Social and Political Justice (2016). That was the substance of our conversation over coffee: a shared love of the autobiographies and memoirs of people of faith. It was material that he was teaching, even as retirement loomed, but it was also an academic subject that was deeply personal.

Like so many others, I first encountered Raboteau the scholarly writer as an undergraduate. Slave Religion—his first book—was all but required reading for anyone interested in the study of American religion. African American religious history is a complicated academic subject. There is not remotely any monolithic view of how Black people have navigated religion in the United States. African American religious history spans the theologies, cultures, experiences, sorrows, and joys of people of African descent navigating a nation that is both home and not quite home. Raboteau’s work grappled with the complexities of diverse communities, for whom religion was a hallmark of identity, history, and legacy.

He was among the first to ask a simple but profound question: What is religion for a people birthed in the cradle of chattel slavery? It is no exaggeration to say that his work changed the trajectory of two fields: African American studies, which had often neglected questions of religion, and American religious studies, which had often failed to study the experiences of African Americans in a rigorous and systematic way. I am among a generation of scholars who owe a debt to the questions he was willing to ask and the seriousness with which he treated the lives, stories, and experiences of enslaved and formerly enslaved people.

But there at the coffee shop in Princeton, I encountered a different Raboteau: the devoted lover of God. He was interested in the faith journeys of iconic American figures, and he was also a willing conversation partner about his own religious beliefs and the journey that ultimately led him to the Eastern Orthodox tradition. Over the next few years, our conversations were primarily theological, as we grappled with the mystery at the center of Christian faith. With his characteristic gentleness, he talked with me about race and navigating the realities of American racism in ecclesial spaces. We spent a great deal of time talking about the Holy Spirit, reveling in the pneumatology that connected his Orthodox faith and my Pentecostal leanings. In those conversations, Dr. Raboteau treated me as a peer and a colleague. And more than that, we were fellow believers.

When you are an undergraduate, you spend far too much of your time trying to hurry up and graduate, to move on to whatever you imagine is next in the real world. I failed to appreciate that I was being taught by a person who had shifted the academic discourse in the field I would later adopt. From those college years, I remember the gentle and kind presence of a man prone to giving quiet, calm lectures in class. Raboteau was the perfect contrast to the Black preaching style of Cornel West, another professor of mine, whose teaching cadence and style I was familiar with as a daughter of the Black church. There was a sense of peace that Raboteau radiated in the classroom, the same peace he radiated in the conversations I was able to have with him when I returned to Princeton as a professor.

I shared with him that his memoir, A Sorrowful Joy, was a book I taught my students time and time again. Because it is short, people often think it will be an easy read. But Raboteau’s vulnerability in discussing his faith, his family, and his failures gives a glimpse into how his life, how all our lives, are filled with painful places and joyful moments. He was never ordained or a member of the clergy, but this small volume ministers to hurting people more palpably than most sermons I have heard. Upon news of his death, I shared with my divinity school community my favorite line from this book, which I carry in my heart. After describing some of his writing students at a program for people with mental illness, he writes, “They teach me. Grace is everywhere.”

In 2013, the Department of Religion at Princeton University hosted a two-day conference in Raboteau’s honor on the occasion of his retirement. I was honored to be able to attend and meet some of his family members for the first time. I also got to meet several of his former doctoral students, many of whom were teaching religion at some of the best colleges and universities in the country. His academic legacy was secure. And I respected that the department he dearly loved gave him his flowers while he could still smell them.

I was probably among just a handful of attendees who had been his undergraduate students. Perhaps one day Princeton will add them up: the hundreds of sophomores or juniors who, in fulfilling their requirements for a degree or searching for an elective, took a class or two with Raboteau during his three decades of teaching there. Whatever the number, we are all better for the intellectual gifts and compassion he freely shared with all who crossed his path. May we all demonstrate that same grace everywhere.