The book editor who inadvertently helped empty America’s pews

Stephen Prothero’s biography of Eugene Exman reveals how the bestsellers he acquired taught people to be spiritual but not religious.

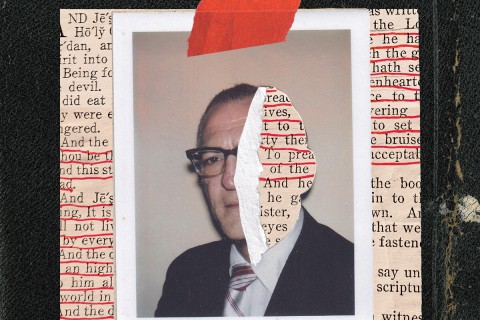

When an elderly woman asked religion scholar Stephen Prothero to visit her late father’s library of religion books, he wanted to ignore the invitation. But when he finally went, Prothero found the books, letters, and personal writings of a spectacularly influential but little-known editor who shaped a century of American religious thought and practice. In God the Bestseller, Prothero suggests that the books this editor acquired proffer a “genealogy of modern American religion—stepping-stones across the stream of American consciousness from Protestantism to pluralism, from dogma to experience, and from institutional religion to personal spirituality.”

The woman’s father, Eugene Exman, worked from 1928 to 1965 as an editor at Harper & Brothers (which became Harper & Row and later HarperCollins, parent company of Prothero’s own publisher). In steering the religion books department at Harper, Exman launched hundreds of bestsellers—most of us in publishing would be thrilled to work on just one—and pulled off historic moves like convincing Martin Luther King Jr. to write his first book. Exman, whom Prothero calls the “dean of religious publishing” in the United States, collected a group of friends—activists, preachers, rabbis, industry titans, and others—and published many of their works. The complicated legacy of Exman’s oeuvre, Prothero writes, “taught millions to hate the word religion and love the word spirituality, and, in so doing, it helped to empty the pews in twenty-first-century America.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

God the Bestseller is a biography in triplicate. Prothero narrates Exman’s journey: from his early years in Ohio, where he experienced a flash of transcendence on the way to a prayer meeting, to divinity school, and then to the world of publishing, where for five decades he honed an intuition regarding which writers could both shape readers’ sense of the Divine and produce books that would sell. Prothero constructs Exman’s vocation as a lifelong attempt to recapture his teenage mystical experience of God by acquiring the work of mystics, saints, and people he thought might become either. “He published books that would help his readers (and himself) in their personal quests for the divine,” Prothero writes, “always with one eye on spiritual practices and another on religion in action.”

The book is also a group biography of those who penned the books Exman edited: King, Harry Emerson Fosdick, Dorothy Day, Albert Schweitzer, Howard Thurman, and Bill Wilson of Alcoholics Anonymous, among others. In addition, the book becomes an entrancing and erudite biography of American religion itself, as Prothero traces how various forces—two world wars, William James’s work, the Social Gospel, mysticism, pacifism, perennial thought, capitalism, racism, and therapeutic spirituality—acted on Exman’s faith and that of his peers and of us.

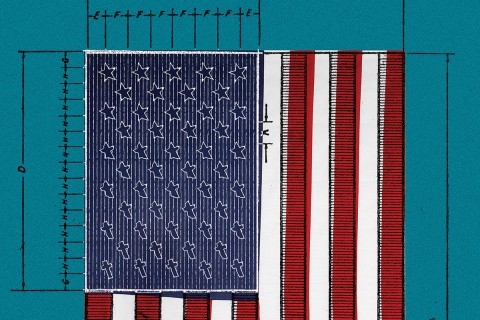

The subtitle of Prothero’s book speaks to the aspirations of many who work in publishing or education or ministry: would that we, too, could transfigure a vast field by laboring on one book, one student, one congregant at a time! Also enticing is the notion that some guy from Ohio might be the Rosetta stone that deciphers not only America’s religious beliefs and practices but our own. “If you wonder what you believe and where you first read about it, he is the likely source,” writes Kathryn Lofton about Exman in her blurb for God the Bestseller. We churchgoers often use the same spiritual lingua franca as the spiritual-but-not-religious folks who now represent more than a quarter of the US population. Indeed, many of us progressive Christians have become so fluent in the glossolalia of the nones and the dones that our vocabulary about God sounds a lot more like our magick-loving neighbor’s than our Baptist cousin’s. Prothero’s book helps us understand why.

Claiming that any one person transformed American religion skates close to hyperbole, but Prothero mostly delivers. He builds a convincing case that Exman both discerned the winds of American religion and directed them. His authors ushered believers away from institutional form to individual feeling, what Prothero calls “the religion of experience.” That kind of religion, he suggests, translates easily into profits for entrepreneurs who capitalize on the longings of seekers as they begin to “flit from one spiritual fad to another in search of the ‘Real Thing.’”

Exman’s legacy is complicated on many counts, and Prothero avoids hagiography. Exman was a White Protestant who palled around with rich folks, with all the failures of White moderates then and now, Prothero notes. His definition of religious diversity, at the beginning of his career, meant “publishing clergymen of various Protestant denominations.” Yet Exman ended up helping readers envision America as a place of religious pluralism rather than as a Christian nation—a great service indeed, and one we apparently need more than ever.

There’s at least one lacuna in an otherwise exceedingly thorough book. Religious speech between evangelicals and mainline Protestants has become almost mutually unintelligible, and Prothero’s book doesn’t inquire as to why. My hunch is that it has something to do with the fact that during the same decades that Exman was acquiring the work of liberal Catholics and Hindu mystics, White evangelicals were ramping up their own publishing apparatus. By 1950, writes Daniel Silliman in Reading Evangelicals, there were 50 evangelical publishers. Those publishers’ missionary stories, Christian romances, and dispensationalist thrillers suggest that Exman’s evangelical peers were pursuing authors with a much different religious vision.

There’s also no mention of agglomeration in corporate publishing, nor of one media empire in particular. HarperOne—Exman’s employer and Prothero’s publisher—is an imprint of HarperCollins, which is now a subsidiary of News Corporation. So while the book introduces readers to one powerful man they probably have never heard of, it fails to mention a less sympathetic character they almost certainly have: Rupert Murdoch. Prothero’s own editor may have waved him away from such a meta move. Yet insofar as the religion of experience succeeds because “its native habitat is the ecology of consumer capitalism,” as Prothero claims, it does so in a specific publishing ecosystem. Media moguls are shaping our spiritual selves at least as much as an obscure religion editor in the 20th century did, and that fact deserves at least a bit of attention.

Still, Prothero’s book proves an engrossing read. In chapter after lively chapter, Prothero shows us an editor doing his job, chasing down and collaborating with the people whose books have shaped my religious sensibilities and yours. Prothero rightly suggests that Exman’s influence grew, in part, from figuring out that religious books are simultaneously consumer products and sacred objects. Exman knew, too, that the dual identities of religious books—as commodities in the market and conduits of the Spirit—are less oppositional than purists of either commerce or ministry might guess. As Vincent Miller writes in Consuming Religion, our pursuit of more stuff and our spiritual longings are both “about the joy of desiring itself, rather than possessing.” The work of editors like Exman is to tap into endless reserves of human longing.

When we’re honest, editors and clergy and teachers can see all the ways we yoke our futures to the fancies of our shareholders and readers, congregants and students. The dirty secret of religion publishing—and any industry that deals with the ineffable—is that we devote ourselves as much to following people’s desires as we do to leading them toward an immortal God. We can only hope that those are, at times, the same thing.