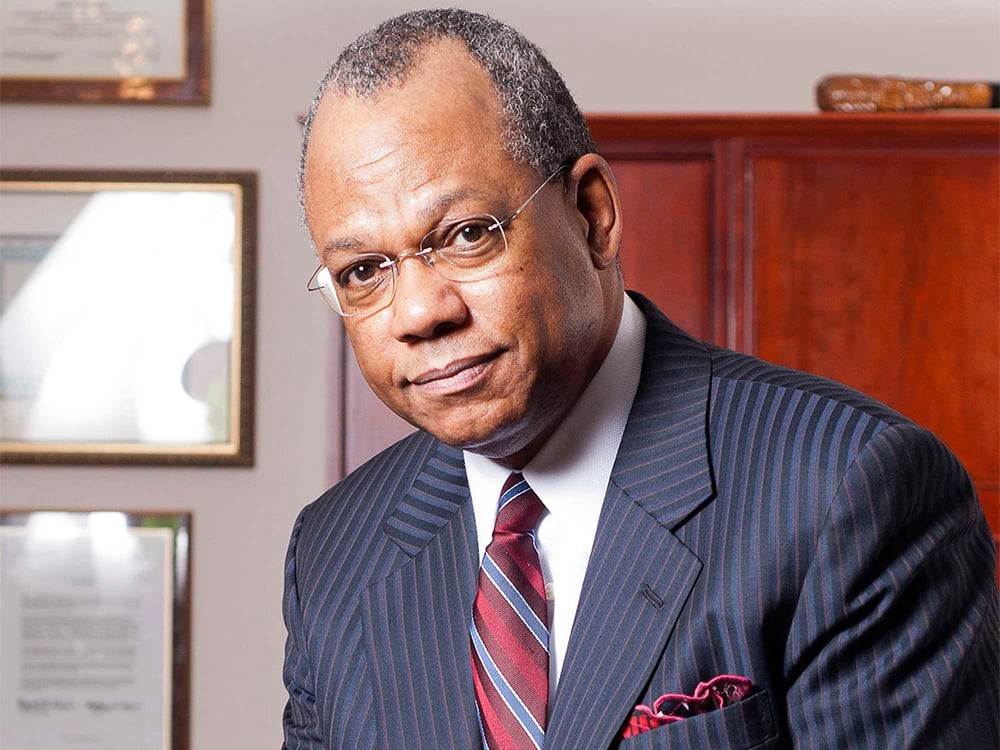

Calvin Butts, leader of Harlem’s historic Abyssinian Baptist Church, dies at 73

Calvin O. Butts III, the senior pastor of New York’s historic Abyssinian Baptist Church, who followed in the footsteps of prominent Black ministers and paved his own path of leadership in education, health and political circles, died Friday, his church announced.

“It is with profound sadness, we announce the passing of our beloved pastor, Reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts, lll, who peacefully transitioned in the early morning of October 28, 2022,” the church stated on its website and on Twitter. “The Butts Family & entire Abyssinian Baptist Church membership solicit your prayers.”

Butts, 73, succeeded Samuel DeWitt Proctor as pastor in 1989 after starting as a minister of the congregation in 1972. He became the church’s 20th pastor, according to the church’s website.

“When we think about Dr. Butts we know that he served the community of Harlem but he served the wider community as well,” said James A. Forbes Jr., senior minister emeritus of Riverside Church, whose church was about two miles away from Butts’. “We have lost a great leader, one who really was a champion of justice and freedom for all.”

Under Butts’ leadership, the church founded the Abyssinian Development Corporation, a not-for-profit that has led to $1 billion in commercial and housing development in Harlem. He also played a key role in the creation of the Thurgood Marshall Academy for Learning and Social Change, a public high school, and envisioned the Thurgood Marshall Academy Lower School, an elementary school that opened in 2005.

Butts was part of a succession of leaders at Abyssinian that included two who served on Capitol Hill. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a former pastor, was a New York congressman, and Sen. Raphael Warnock served a decade as a youth pastor and assistant minister at the church under Butts.

“Reverend Butts was my pastor,” Warnock said in a tweet on Friday. “He mentored, trained, and inspired me at the beginning of my career; I owe much of who I am today to him.”

Butts, a Morehouse College graduate, also was an active contributor in the higher education field, serving for two decades as president of the State University of New York at Old Westbury and overseeing the creation of its first graduate programs. He was a visiting professor in Fordham University’s education graduate school.

Butts was known for his outspokenness on issues ranging from misogyny in rap music to the need to address HIV/AIDS.

Barbara Williams-Skinner, co-convener of the National African American Clergy Network, recalled Butts’ work with people across denominations and faiths, including joining the late activist C. Delores Tucker to condemn what he called “vile” and “ugly” lyrics in gangsta rap.

“To me it bore witness to his respect, high respect for women,” she said. “It got him probably into a lot of conflict with some in the music industry. But Calvin Butts was a man with a lot of backbone. He didn’t mince words.”

By the 1990s, Butts was among the early Black clergy advocates for HIV/AIDS education and prevention, and by 2001 he was a founding member of the board of commissioners of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS, now known as the National Black Leadership Commission on Health.

“His voice gave voice to so many within our congregations who really were members in the shadows of our steeples,” said Darryl Gray, director general for social justice for the Progressive National Baptist Convention. “And he brought these people out of the shadows of our steeples with his voice and with saying to the Black church, to Black preachers, it is alright to have these conversations. It does not change your theology.”

According to its website, Abyssinian is triply aligned with the American Baptist Churches USA; the National Baptist Convention, USA; and the Progressive National Baptist Convention.

While serving as the social justice chair of the PNBC, Butts spoke about the political activity of Black churches, saying they needed to stand apart from both white liberals and conservatives amid divisive partisan politics.

“We have our own view of the gospel message which is the only authentic view,” he said at a National Press Club news conference ahead of the 2018 midterms at which he critiqued members of the religious right such as Franklin Graham, Jerry Falwell Jr., and Paula White.

“They’re heretics as far as we’re concerned—hypocrites,” said Butts. “And we need to be unafraid to say this and stand firmly on who we are.”

His minister colleagues remarked on Butts’ contributions while noting they may not have always agreed with him.

“He was an educator, and a Pastor of the highest level, he served both duties for decades,” the Rev. Al Sharpton, president of the National Action Network, said in a tweet. “We found ourselves differing at times but we’d always come back together.”

Forbes, who last spoke with Butts in December 2021, when his ill colleague asked him to preach at the funeral of jazz pianist Barry Harris, said agreement came on the ministers’ joint belief that they were following a divine calling.

“You did not relate to Butts based on the assumption that he always saw things the way you saw them,” Forbes said. “And it was not necessary that we always had to see things the way he saw them. But we knew that his faith was deep and that he wanted to make a difference that would bring glory and honor to God.”

Other religious and political leaders reacted to Butts’ death.

“Rev. Butts was a servant-leader whose legacy will live on through those he inspired,” said W. Franklyn Richardson, chairman of the Conference of National Black Churches, in a statement. “He was a titan of Harlem who understood that a faithful community had to be as strong beyond the church doors as it was in the pews.”

Added New York Governor Kathy Hochul in a tweet: “Rev. Butts embodied true spiritual leadership — with a commitment to faith, community, & mentorship that I was honored to witness in our work together.”

Butts often called for the church to be ready to serve the people outside its church walls and not just those within its pews.

“You’ve got to do everything,” he said in a 2006 speech at a meeting sponsored by the Seventh-day Adventist Church. “Churches, schools, health care, housing. You’ve got to take your people up to heaven so they can see what God has in store and then take them down to the ground so they can see what work is to be done.” —Religion News Service