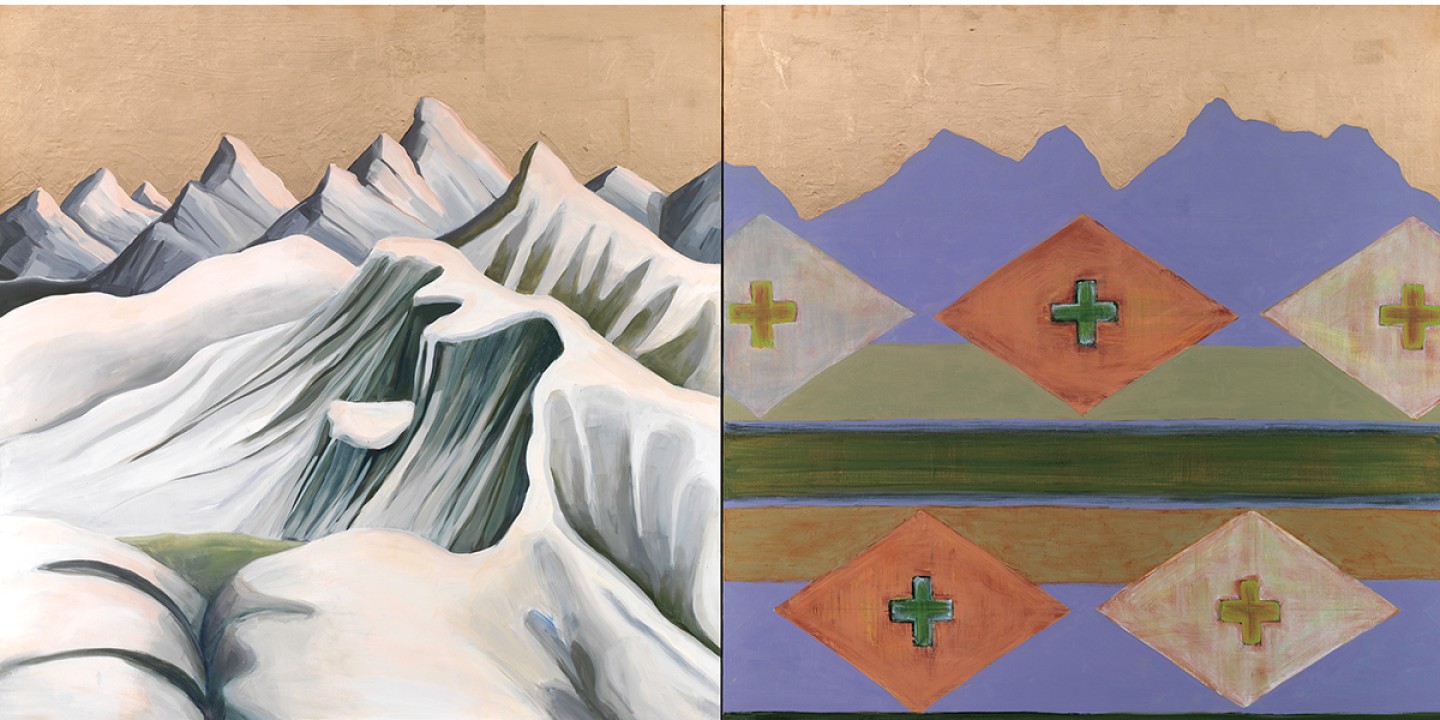

Can these stones live?

Some Indigenous traditions suggest that rocks are sentient. What does this mean for how we humans relate to them?

We begin with stones. In the Anishinaabe universe, even before the thoughts of Kiche Manidou—the Creator, or Great Mystery—there was what Louise Erdrich calls “a conversation between stones.”

When I was in ninth grade, my science teacher asked the class if stones were alive. We were learning the seven criteria of life. After reviewing the list, we said that no, stones were not alive. He asked us if we were sure. We went over the criteria again and told him yes, we were sure. He said that it might be that stones did things more slowly than we could measure. Could it be that we lacked the ability to see these things in stones? Or could the criteria be wrong? Then he smiled. This possibility—of something like a stone being alive—has stayed with me.

Ojibwe Anishinaabe author and academic Lawrence Gross would agree with this science teacher. In Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being, Gross writes about the Anishinaabe language being more suited for quantum physics than English because it understands the dynamic nature of creation. It is a verb-based language, meaning that it talks about what things do rather than what they are. We are not human beings; we are humans being.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Anishinaabemowin, like many other languages, is concerned with the relationships between things. This is revealed by the kinds of verbs that are used to describe what is happening. In English, I would say that the man hit his dog or that rain hit the ground, using the same verb. In Anishinaabemowin, we use different verbs depending on whether the thing being hit is animate or inanimate. For the Anishinaabeg, stones may be alive. Our word for stone is asin, and it is animate.

The Indigenous people of Australia also understand stones to have deep knowledge, holding memory and having spirit. Tyson Yunkaporta, an Australian writer and carver and member of the Apalech clan, writes about the sentience of rocks in Sand Talk. He says you can’t just pick one up and take it home, because you disturb its spirit—and it will disturb you. At Uluru, the massive sandstone monolith formerly known as Ayers Rock, tourists are told not to take rocks home. Some do anyway—and then many report having bad dreams and bad luck. There is a shed at Uluru full of the rocks people have sent back.

I think about my own collection of stones—stones that I have picked up from various vacations and brought home. It’s been a while since I’ve done that. I didn’t have any kind of epiphany, no bad dreams or bad luck. One day, I simply stopped doing it. I can’t even say it was a conscious decision. Sometimes we learn to listen to things without realizing it.

The Sámi, an Indigenous people who live in Northern Europe, also talk about living stones. In The Hebrew Bible and Environmental Ethics, Norwegian Hebrew Bible scholar Mari Joerstad invites us to consider the world that the ancient Hebrew writers lived in as a “world [that] contained sentient, spiritual beings.” This world sounds more like what I hear from Anishinaabe authors and elders than anything I hear in church. Joerstad draws together the sense of the ancient Hebrew with her knowledge of the Sámi people. She writes about Sámi reindeer herder and philosopher Nils Oskal describing the relationship that the Sámi have with sieidi stones, to which they give gifts of coins or tobacco. Outsiders often mistake this courtesy—this recognition of life and connection—for worship. But it is part of a way of understanding humans’ place in the world: we are in the midst of sentient beings with whom we are in relationship, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Are the stones alive? Can rocks cry out?

I want us to consider our relationship with land—to think about it beyond squabbling over ownership and rights, to think about responsibilities and reciprocal relationship and of ourselves as a part of creation rather than apart from it. What if the land is a being in its own right? That concept is not as foreign as you might think. And what if the land and all that grows from it and on it and in it are sentient beings in their own right? Then we need to make material changes that restore the land, rooted in the recognition that the land belongs to itself and everyone belongs to the Creator.

Land is our first relationship, and it is the first relationship that we need to restore. We are used to standing on it, planting in it, and marveling at it, but our relationship with it is complicated. Colonialism has disconnected us from land, severed us from that first relationship—often through violence. We buy land and sell it, extract resources from much of it, and then idealize parts of it. For as long as colonists and their governments around the world have taken Indigenous people’s land for themselves, we have sought to be restored to it.

In Salmon and Acorns Feed Our People, sociologist Kari Marie Norgaard includes a case study about the Karuk people, a tribe in Northern California whose name literally means “the ones who fix the world.” She details how the loss of land has impacted the Karuk people and how they are restoring their landholdings and the ways in which they shape the environment. They work with fire in a kind of pyro-epistemology—a term coined by the Cree-Métis anthropologist Paulette Steeves—to manage their environment. This protects the waterways, which in turn provide salmon, as all these things are interconnected. Food sovereignty, which is tied to land, is a cycle of relationships, not just access. You drop one stone—say, by building a dam—and the unintended consequences ripple outward.

Because the doctrine of discovery allowed European states to claim whatever land they found, reservations aren’t generally owned by the tribe that lives on them. The land is owned by the government and “held in reserve” for the specific use of Indigenous people. That is a precarious foundation for a community, as many tribes have experienced. The Wisconsin Menominee found themselves deemed “ready for termination” after achieving some economic success in the lumber industry, and in 1954, they lost their lands and their tribal status. The Menominee were reinstated in 1973, but the economic impact of termination was devastating.

We cannot talk about restoring our relationship to the land without talking about restoring the land to relationship with the people from whom it was taken. The slogan “Land Back” started with a tweet, which became a hashtag, which became a rallying cry for a movement of land restoration and Indigenous sovereignty. The movement has been in existence for hundreds of years; it’s just that now it has a name.

Settlers and migrants and the forcibly displaced get worried when Native people start talking about Land Back. What about their houses? Where will they go? Unable to imagine any scenario other than what settler colonialism unleashed on us, people assume that Land Back means evictions, relocations, and elimination. In some cases, that might be appropriate. People buy lakefront vacation homes that crowd Indigenous people out of traditional rice beds, as Drew Hayden Taylor documents in his 2019 play Cottagers and Indians. Luxury hotels and investment properties take up space, while Indigenous people are made homeless in their own territories.

But wholesale eviction was never what Native people intended. From the earliest treaties, we offered a way to live together in peace, friendship, and respect. And although we are often, and I think reasonably, looking for change in ownership, at its core, Land Back means profoundly changing our relationship with land. We need a reciprocal relationship with the land, one that recognizes the hubris of ownership and the limits of a colonial way of living that destroys for the sake of replacing.

When the colonists originally came to the land they would call America, they saw themselves as latter-day Abrahams coming to a new promised land. But the colonists missed a key point about Abraham. He did not enter the land as a conqueror; he entered as a supplicant, as a guest. He lived among the people of Canaan, and when God threatened to destroy the city of Sodom, Abraham argued with him, pleading for justice.

The practice of jubilee—restoring land to the original families—asserts both the temporary nature of our ownership and the enduring nature of the Creator’s sovereignty. Our connection to the land is in our relationship with it, not our ownership of it. When we make it a thing that we can buy and sell, we not only sever our relationship with it, we sever it from its relationship with the Creator. That is something we should all take seriously.

Sometimes Native tribes identify particular places as sacred, perhaps in the hope that this will find some traction with those who are sympathetic to such things. But recognizing that Native places are sacred has never protected them from violence; in fact, it has ensured it. The US National Park System has been displacing Indigenous people for more than 100 years. Just like governments use the language of safety, conservationists use the language of environmentalism to push aside the original peoples of the places where the parks now exist.

The idea of restoring national parks to the Native peoples from whom they were taken is gaining some interest in the United States and Canada (see “The forced migration of Native Americans pushed them to inferior land,” December 28, 2021). In the May 2021 issue of the Atlantic, Ojibwe writer David Treuer describes how the US government displaced the Miwok tribe from the land that would, 39 years later, become Yosemite National Park. This story repeated itself across the United States and Canada: Indigenous peoples were banished from what conservationists saw as pristine wilderness. These parks were seen by settlers, in the words of Treuer, as “natural cathedrals: protected landscapes where people could worship the sublime. . . . an Eden untouched by humans and devoid of sin.” However, he goes on to point out, these places were never untouched. In a reenactment of the Fall, the settlers cast out the original people and called it pure.

Treuer, and many others, argue that if the US government is to take seriously ideas of conservation and reconciliation, these lands should be placed under the control of the tribes from whom they were taken. He notes that there is precedent for this in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. In Canada, the territory of Nunavut was separated from the Northwest Territories in 1999 and is largely administered by the Inuit, who make up most of the population. In Australia, many significant natural landmarks are under the control of the Indigenous peoples: Uluru, for example, and almost half of Australia’s Northern Territory.

In New Zealand, the Raupatu lands component of the Waikato River claim was settled in 1995, returning land to the Maori tribe that had originally lived there, including lands that were under existing crown ownership: the University of Waikato, Te Rapa Air Force Base, the Hamilton courthouse, and the police station. These pieces of land within the city boundary of Hamilton, New Zealand, are now Maori land. This arrangement has provided the tribe with a tax base from which they can make decisions about development, and it involves them in a partnership with the city where they have real power to influence decisions.

Individuals also sometimes donate or sell property to tribal governments. In 2012, the Red Cliff Ojibwe of northern Wisconsin opened Frog Bay Tribal National Park, which includes tribal lands as well as lands that they purchased from David Johnson, a retired professor. Johnson learned that the tribe wanted to purchase the land he and his wife had bought decades earlier but could not afford it. He sold it to them at half of its appraised value, saying that he had “always felt a little embarrassed at owning property that should have been in the tribe’s hands all along.”

Indigenous peoples often speak of belonging to the land. We say that the land owns us. It was into this kind of relationship that God invited the Israelites. The Year of Jubilee was more than an economic reset to prevent the accumulation of wealth; it restored each family’s relationship to the land of their forebears and reminded the people that they did not own the fields that they purchased. The Year of Jubilee is long past. It is time to restore the land to the original people.

In the United States and Canada, institutions—churches, colleges, and settler organizations—are beginning to recognize their colonial history. As they try to improve their relationships with Indigenous peoples, some institutions are talking about decolonizing. Decolonizing is not another word for antiracism or anti-oppression; it is not just another way of saying diversity and inclusion. As Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang wrote a decade ago, decolonization is not a metaphor. It means returning the land to the people from whom it was taken. We could be the most antiracist society on earth, but as long as our institutions rely on stolen land and the displacement of Indigenous people, the United States will remain a colonial state.

What might happen if churches and businesses returned their land to the Indigenous people from whom it was taken? They would run the risk of eviction, that’s true. But how would it change their behavior now that they are motivated to avoid eviction? How would churches act toward Indigenous peoples to ensure that their yearly lease gets renewed? What practices would businesses put into place to keep their place? How would that change in ownership create a change in priorities? What ripples would that have in the broader community?

Restored relationship is always a possibility, and exile is not forever. But we must listen to the stones and what they might be telling us. We must listen to and acknowledge the land’s grief.

In the ancient Middle East, drought was often connected with mourning as the land’s physical response to an emotional state. Just as a Hebrew mourner would fast and pour dust over their head and body, so too the land expresses her grief by fasting and covering herself in dust. “Human action has caused desolation and destruction,” Joerstad writes. “Further proof of human perfidy is their inattentiveness to the suffering of other creatures. The earth is left with no option but to cry directly to YHWH.” The land mourns and wastes away because of not only the things that humanity has done but the things it has not done, such as our lack of care for those who suffer. The land has absorbed the blood of that suffering, and it mourns.

But it also responds with joy. The same prophets who describe a land fasting and covering herself with dust in response to human wrongdoing and harm also describe beautiful scenes of rejoicing and jubilation upon the return of the people. “The desert and the parched land will be glad; the wilderness will rejoice and blossom,” the prophet Isaiah says (35:1).

I reconnected with my father when I was in my late twenties, and shortly after that, he took me home to Sioux Lookout. It’s a long drive from Niagara Falls to Sioux Lookout; people don’t often realize how massive the province of Ontario is. You can start in Ontario, drive for 24 hours, and still be in Ontario. The geography changes, and although the highway goes up and down as it travels around Lake Superior, you are mostly going up into the Canadian Shield. There are long stretches empty of people, towns that you blink and miss.

There was no road into the reserve, so we stayed at a cabin nearby. My father pointed across the lake to Frenchman’s Head and told me that’s where the reserve is. It was the first time I had been home since leaving as a toddler. Still, as I looked out over the lake, I was surprised by an undeniable sensation that the land and water remembered me. I stood beneath stands of black spruce and looked across the lake, and it felt so familiar that it ached. I went down to the rocky beach and put my hands in the water, and it remembered me. I cannot tell you how or why I knew that. It was completely unexpected, this sensation of both remembering and being remembered. I can only describe it as electric.

Since that time, I have had other fleeting reminders that the land is alive in ways I am only beginning to understand. I mentioned earlier that I had stopped collecting stones, and that is mostly true. But this past summer when I went home again, we camped at provincial parks around Lake Superior. At one of them, my husband brought me a stone he had picked up on a beach covered in round stones. When I held it in my hand, it felt like mine. Not mine like a thing that was now in my possession, but mine like my children are mine and my parents are mine. We belonged to each other.

I thought about the roundness of this granite, the smoothness of it, and the amount of time that must have taken. How patient the stone and the water were. The length of that relationship. Stones are ancient, older than water, older than time. Bones of the earth. They’ve been through so many worlds, so many floods, and they hold all the memory and knowledge that comes with it. Eternity sits in my hand, and it ties me to home.

This article is adapted from Krawec’s Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimaging Our Future, forthcoming from Broadleaf Books. Used with permission.