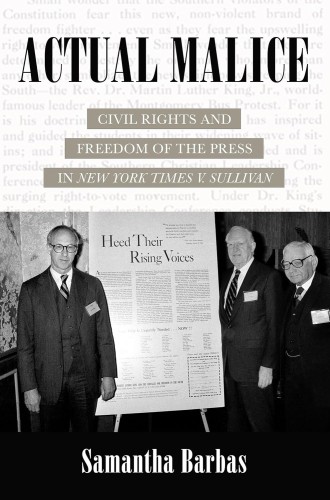

The case that revolutionized libel law

Samantha Barbas’s history of New York Times v. Sullivan shows how easy it was to weaponize the law against southern civil rights leaders.

“Heed Their Rising Voices,” proclaimed the full-page ad that appeared in the Tuesday, March 29, 1960, edition of the New York Times. The ad requested donations to support the legal defense of Martin Luther King Jr., who had recently been arrested in Alabama on a trumped-up tax evasion charge. It dramatically recounted recent nonviolent student civil rights protests, including the “unprecedented wave of terror by those who would deny and negate” the students’ rights, but the ad did not single out for criticism any specific person in authority.

The ad was hastily put together and contained several errors, including a claim that officials responded to student protest by padlocking the dining hall at Alabama State College in Montgomery in an attempt “to ‘starve’ the students ‘into submission.’” Impressed by its high-profile signatories—including Eleanor Roosevelt, Jackie Robinson, and Harry Belafonte—the Times advertising acceptability department declined to undertake its usual fact-checking process for submitted ads. At the last minute, Bayard Rustin, who organized the ad, added as endorsers the names of 20 southern Black ministers associated with King—without getting their permission. These included four Alabama ministers: Ralph D. Abernathy, Fred L. Shuttlesworth, S. S. Seay Sr., and J. E. Lowery.

Incensed that the ad accused them of starving college students, Montgomery officials, including commissioner of public affairs L. B. Sullivan, prepared to initiate a libel suit against the Times—and the four Alabama ministers. Along with threatening civil rights leaders with financial ruin for challenging segregation, adding the ministers to the suit ensured that the case would be heard in the more sympathetic forum of an Alabama state court. When no retraction was forthcoming—the ministers didn’t respond to the request because they didn’t believe they could retract something they hadn’t said in the first place—the Montgomery officials sued.