I want to be an eccentric when I grow up.

My role models? A bevy of beloved church members I have known over the course of my life. For instance, Mrs. P., who wore large, fantastic pieces of jewelry from her travels all over the world and reliably brought stewed rhubarb to every church potluck, portioned out in Dixie cups on a tray, though I am not sure anyone ever ate any of it. There was M., who wore “purple, purple—everything purple,” as she would say, because her ex-husband didn’t like the color. Once they were divorced, it was the only color she ever wore.

There was R., who had a long, forked red beard like Yosemite Sam and asked me to please not call him “Sir,” because he was a union man and “not a manager.”

There was F., who always said exactly what she thought, including the time I showed up in her hospital room (as her pastor), unannounced, and she said, “Oh no. What are you doing here?”

I love these people because they were unafraid to be fully themselves. I mean, sometimes they were delightful to be around and sometimes they were irritating in their unabashed skill for self-expression. And yet they were not selfish or self-centered people. Like most church folk, the vast majority of eccentric church members I have known were generous in giving and active in service. It’s just that they knew how to live as themselves, often as older adults, after living lives that weren’t easy. Irenaeus writes, “For the glory of God is a living person,” often translated instead, a bit on the slant, as “The glory of God is a human being fully alive.” Both versions ring true to me.

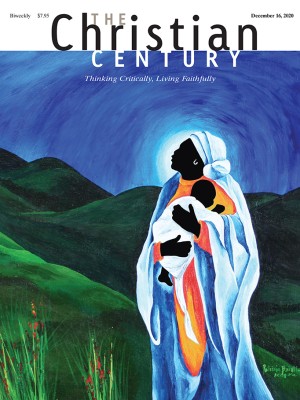

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

However, the world does not tend to admire or reward people who are fully themselves, because they can seem odd, unusual, unstylish, and unpredictable. And so eccentric people are often ridiculed or ignored. Perhaps this is why many of us, including me, are often hesitant to indulge our own eccentricities—to be fully honest, fully giving, fully ourselves. We don’t want to seem too weird. We don’t want to feel as though people are cocking an eyebrow at us, avoiding us, or laughing at us instead of with us.

I like to imagine that Simeon and Anna were eccentrics. Luke tells us they are elderly adults, significant personalities in Jerusalem, and attuned to the movement of the Spirit. In other words, they were probably a bit wacky, the ancient Jewish equivalent of church nerds. It sounds as though Anna lived in the temple full time, and Simeon must have been there an awful lot. I picture them welcoming temple visitors, chatting with the regulars, and alerting the priests when something was not being done, ahem, correctly. I imagine that some people sought them out, while others actively avoided them. In short, they might be like some church members I know. They may even be a little bit like me—and you, if you are reading this magazine.

It seems right on the money to me that these two are the first Jewish elders who recognize Jesus and welcome him to the Temple. I don’t know about you, but if a sketchy-looking couple arrived in my congregation with a baby, I have no doubt that it could only be one of my beloved eccentric parishioners who would be perceptive enough to recognize the Messiah and his parents walking in the door—and uninhibited enough to greet them with a prayer of thanksgiving and maybe even a prophetic warning to boot.

While Flannery O’Connor said, “You shall know the truth, and the truth will make you odd,” it was Jesus who said, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly” (John 10:10). Over and over again, Jesus invites people to live abundant lives through his healing, truth telling, sharing of meals, and teaching. He calls them by name, asks what they want or what they are seeking, and recognizes that there are individuals within the crowds following after him. Many of the powers and principalities of his time thought Jesus was an eccentric, too—until he really began to attract attention, and they started to see him as a traitor, a blasphemer, and a criminal.

Jesus was born among outsiders and eccentrics, and he sought them out in his ministry: the poor, the disabled, the foreigners, the sinners, and the weirdos. In fact, the Bible tells us that God has a penchant for calling eccentric people to be his prophets, leaders, healers, and teachers—people like Abraham, Deborah, Rahab, Elijah, Jeremiah, and Mary Magdalene, among many others. Perhaps this was because they were less worried about what others thought of them and more focused on listening for what God was asking them to do and be for others.

Being abundantly and fully ourselves is a way to serve God: to be the person God made us to be, no matter how odd or eccentric. Perhaps, in so doing, we might more fully be able to love God and serve others. Perhaps, like Simeon and Anna, we would be more likely to recognize Christ in our midst and greet him with thanksgiving. After “for the glory of God is a living person,” Irenaeus continues, “and the life of a person consists in beholding God.”

So why am I waiting until I grow up to become an eccentric? Maybe, in truth, I already am one.