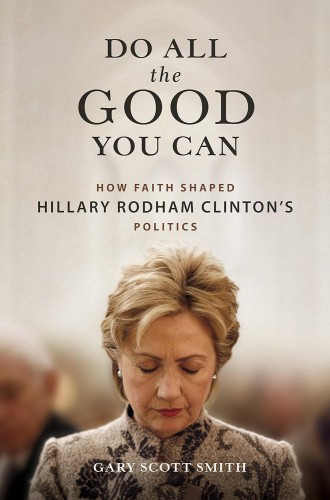

The deeply Methodist Hillary Clinton

Biographer Gary Scott Smith argues that Clinton’s faith lies at the very core of her identity.

The American political scene is pockmarked by division and disagreement, but it seems incontestable that the public figure who has been most reviled and vilified over the past half century is Hillary Rodham Clinton. As Gary Scott Smith records in this remarkable biography, Clinton has been accused of all manner of chicanery and criminality, including murder. “She has been mocked as a witch, a bitch, a feminazi, a slut, a daughter of Satan, a whore, a castrating ball-breaker, and a Marxist,” Smith writes.

That endless stream of vitriol, especially the references to Satan and demons, is incongruent with the portrait that Smith provides in Do All the Good You Can. Smith is by no means uncritical. He’s quick to acknowledge Clinton’s occasional eliding of the truth, and he doesn’t hesitate to point out the inconsistency of an advocate for the poor seeking riches for herself. Yet he demonstrates throughout the book that “Clinton’s faith is more deeply rooted and fervent than many supporters, opponents, pundits, and biographers have recognized.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Methodism, Smith argues, lies at the very core of Clinton’s identity, an observation corroborated by friends, colleagues, even critics—and by Clinton herself. When she joined the youth group at First Methodist Church in Park Ridge, Illinois, as a child, she came into contact with Don Jones, a Drew University graduate and youth pastor, who introduced her to the social gospel. She soon found herself struggling to reconcile her enhanced understanding of the faith with her political identity as a “Goldwater girl.”

That struggle continued for some time, and the importance of individual responsibility persisted in Clinton’s thinking, even as she putatively waded into the tides of liberalism. Smith walks us through what by any measure must be reckoned a remarkable career: Wellesley, Yale Law School, first lady of Arkansas, first lady of the United States, the Senate, secretary of state, presidential nominee. Throughout, the author braids Clinton’s faith into her actions and policies. Her commitment to shoring up the public educational system in Arkansas, for instance, derived at least in part from Clinton’s religious commitment to those less fortunate. The fact that Americans know little about Clinton’s theological moorings, Smith suggests, is due to the backlash she encountered to her religious statements. For example, following her “Politics of Meaning” speech in 1993, she was characterized as pious and self-righteous.

Smith confirms what the rest of the world suspected, namely, that the revelation of Clinton’s husband’s sexual liaison with Monica Lewinsky was utterly devastating. This was certainly not the first infidelity, but she found the public scrutiny of her marriage humiliating. Struggling in the slough of despond, she consulted with religious advisers, including Billy Graham. She drew on her faith as she ultimately decided to remain in the marriage.

Not surprisingly, Smith expends a great deal of energy analyzing the 2016 presidential election, the first time a major political party nominated a woman. The author cites several reasons for Clinton’s loss. Why did 81 percent of White evangelical voters support a thrice-married, self-confessed sexual predator and former casino operator who could not even fake religious literacy over a devout and faithful Methodist? Smith faults Clinton for not talking more about her faith, for not enlisting the support of evangelical leaders, and for apparently rejecting Tony Campolo’s offer to create an Evangelicals for Hillary group.

All those factors, together with the blunder of using a private email server for official business, doubtless played a role. Still, I have to believe that Smith captures the central problem in a short, declarative sentence: “Evangelical disdain for Clinton had been building for a quarter century.” If anything, Smith underestimates the duration and the durability of the opposition.

This spiritual biography is filled with astute observations, many of which arguably call for fuller treatment. Smith notes, for example, that the Democratic Party platform has reflected Methodist social justice teachings ever since the 1972 candidacy of George McGovern, a Wesleyan Methodist seminarian and student pastor. Smith also argues that Hillary was “more personally devout” than any Democratic nominee in recent decades except George McGovern and Jimmy Carter.

That devotion did not propel Clinton to the presidency, in part because, as Smith writes, she “rarely explicitly connected her political positions to biblical precepts.” The Bible Clinton reads and quotes with such alacrity says something about hiding one’s light under a bushel.