Jesus turned his public humiliation into solidarity

He turned it into love and care for humiliated others.

I picked up Stephen Nissenbaum’s The Battle for Christmas a few months ago to read some Christmas history. I found one section in the book pretty disturbing. It describes a late 19th-century activity in which well-to-do New Yorkers paid admission to watch the city’s poor people eat. These immense public dinners were held at the old Madison Square Garden during the holiday season, with more than 20,000 in attendance. Billed as gala events, the dinners featured galleries and boxes filled with prosperous, well-fed people eager to gawk at hungry children eating.

These public spectacles reeked of exploitation, of humiliation elevated to a spectator sport. An 1899 New York Times article with the headline “The Rich Saw Them Feast” told of “pilgrims from the illimitable abodes of poverty and wretchedness” waiting to enter Madison Square Garden for a meal while all paying spectators were seated—“men in high hats, women in costly wraps . . . many who had come in carriages and were gorgeously gowned and wore many diamonds.” As if to keep the rich from mingling too closely with the poor, gifts for the children were dangled from ropes and lowered by pulley systems attached to the roof.

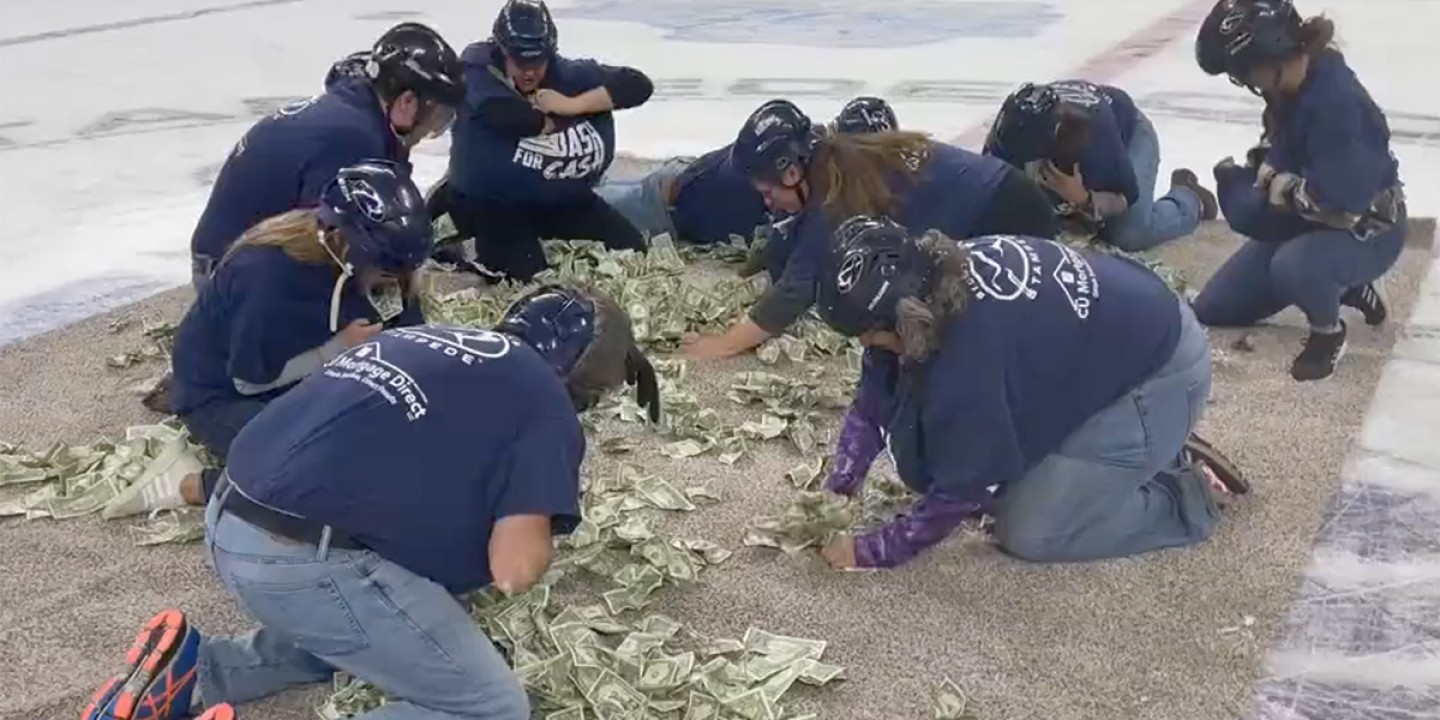

Two decades into the 21st century, we might suppose that humiliation as sport and public spectacle is long out of vogue. Not so, of course. Contemporary examples abound. A couple in Volusia County, Florida, recently forced their preteen son to stand at an intersection and hold a sign reading, “I am a bully. Honk if you hate bullies.” During a hockey game’s intermission in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, last December, ten public school teachers got on their hands and knees at center ice to scoop up $1 bills from a $5,000 pile of cash. As much money as they could hastily stuff into their pockets and shirts became theirs for buying classroom supplies. The dystopian Dash for Cash event, complete with cheering fans, carried particular irony in a state that ranks near the bottom nationally for spending on education.

Suffering abasement at the hands of others and then having that derision reach spectator-sport status is something with which Jesus was well familiar. That crowds publicly mocked, taunted, and ridiculed him is central to the biblical narrative. What he did with this humiliation is fascinating. Jesus “let things be done to him,” Henri Nouwen once wrote when defining the word passion. Jesus did this for the sake of turning this humiliation into love and care for humiliated others. As people cast lots or threw dice for his clothing—an uncommonly explicit example of humiliation as sport—he assumed the mockery unto himself in such a way that others could witness his total absence of self-importance and, in the end, encounter his deepest self.

Richard Rohr writes of “hav[ing] prayed for years for one good humiliation a day” and then carefully watching his reaction to each humiliation. He wasn’t praying for others to bring insult and ridicule upon him so that they could spectate with glee. He was looking instead for a daily opportunity to crush any ego-inflating or idealized self-image that he had of himself. Rohr’s effort to resituate humiliation from public spectacle to inner purpose may resemble, in a small way, what Jesus managed to exhibit so selflessly.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “From spectacle to solidarity.”