Mary’s song reveals her politics of mercy

I think Jesus learned his prophetic ministry from his mother.

Jesus must have learned his prophetic ministry from his mother. She was the one who said, “The Lord has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; God has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty” (Luke 1:52–53).

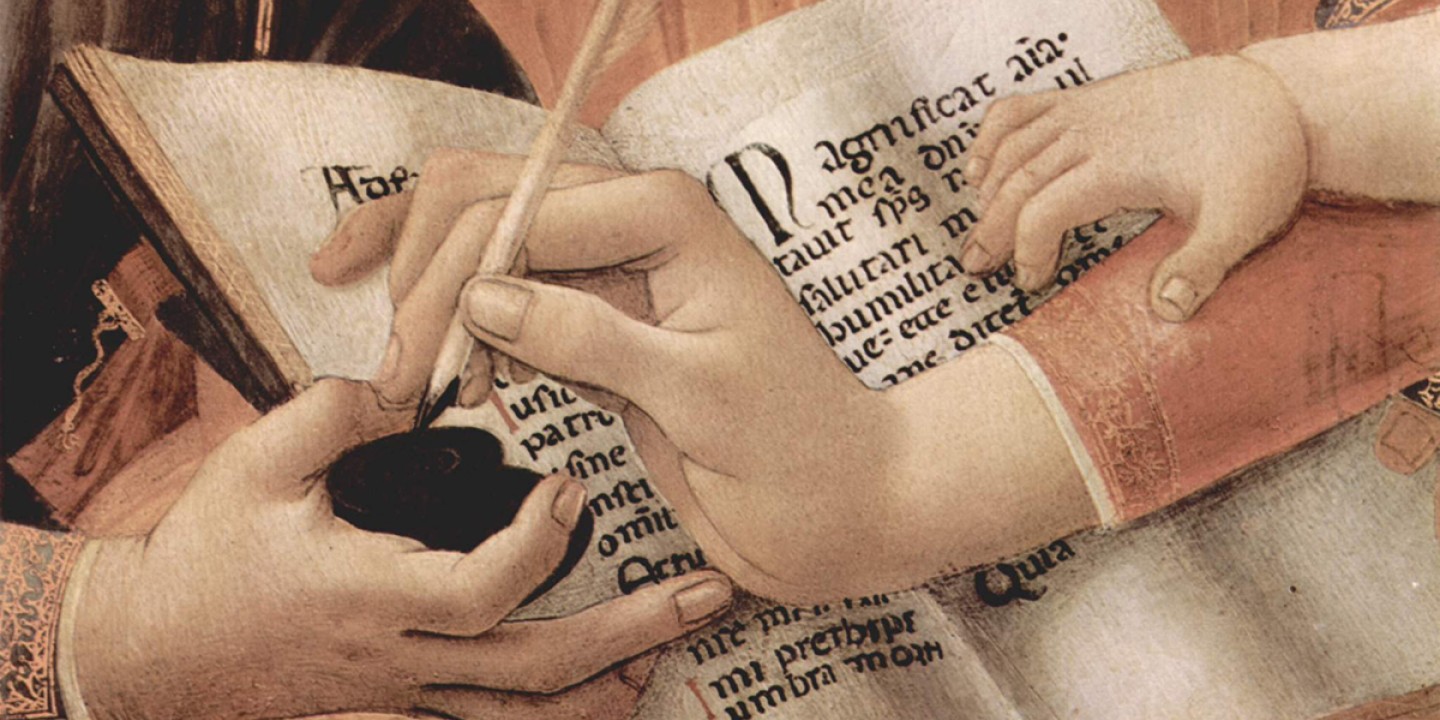

Jesus learned this gospel when he was a child, a baby, as he fussed at his bedtime. He learned his message from Mary, as she held him in her arms, rocking him, whispering her song, comforting him with dreams of a new world—the Magnificat as a lullaby. Mary preached with a song of joy. Political power is about who has a voice, who can speak, who we listen to. And here, at the beginning of Luke’s Gospel, the voice we hear is Mary’s.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

“Truly,” she says with authority, “from now on all generations will call me blessed” (1:48). She knows who she is; she knows what God has done, not just for her but for all of us through her. It will mean a transformation of the world, a structural overhaul of society. The powerful will be brought down from their thrones and the lowly lifted up.

Mary prophesies a new political arrangement, which will involve the abolition of the old systems of power. This revolution springs from the advent of “God’s mercy . . . from generation to generation” (1:50). She sings her song “in remembrance of God’s mercy” (1:54), which shatters the institutions of injustice that threaten and imprison. Mercy will melt the iron grip of oppressors. Mercy means her liberation and ours.

Racism imprisons our lives. The organizing principle of social relations in the United States has always been racial capitalism, as Cedric Robinson argued in his 1983 classic Black Marxism. Racism structures the institutions that govern us, that slot our lives in hierarchies of human value. Our world operates according to the rule of racialized exploitation.

The 2016 election of Donald Trump, whose campaign outlined a trajectory for racial power, emboldened White supremacists to declare their beliefs on street corners. They felt at home again in their country—comfortable enough to gather, in June 2017, at the North Carolina State Capitol building in downtown Raleigh.

With a 75-foot state monument to “Our Confederate Dead” towering above them, a group of 70 White people, mostly men, assembled with their guns and combat gear to spew bigotry, to reclaim this land as their land. Some wore the insignia of militias, the Oath Keepers and Three Percenters, stitched onto their military surplus store clothing. One, with a megaphone in one hand and a Bible in the other, preached racist slander about Islam.

They stood behind a row of riot police, the officers’ backs to the armed White nationalists as if protecting them and their monument from our crowds marching through the streets. I was there with for a rally in solidarity with our Muslim neighbors. The militiamen waved their “Don’t Tread on Me” flags and shouted venomous aspersions, proclaiming fantasies of ascendancy, the delusions of White power, while we—an amalgamated body politic, our bloodlines connecting us to peoples around the world—celebrated the joy of mutual welcome. “No matter where you’re from,” signs in our crowd announced, “we’re glad you’re our neighbor.” Unbeknownst to the people who held them, a Mennonite congregation in Virginia designed these placards, which have made their way into neighborhoods across the country—signs to conjure a hope for a society different from the one we have.

Mary prophesies the joy of a reconstructed society, a world where she and her people will be released from oppression, freed from an abusive regime. I bet Mary would have joined our dancing and chanting in Raleigh, our flagrant rejoicing in the streets, under the malevolent gaze of ethno-nationalists. Drums and whistles accompanied our march as we flowed through downtown. A group of Arab women—keffiyehs covering their heads, scarves wrapped around their shoulders—were playing plastic kazoos with pictures of Disney princesses on them, as if they’d stopped at a toy store on the way and scoured the shelves for a suitable instrument to counter the slurs of militarized White supremacists. I saw a cluster of young women in hijabs dancing to the music. Children soon circled around to twirl and twist with fearless joy.

Mary’s politics of mercy announces the remaking of this world so that women in keffiyehs can play their Disney kazoos and young people in hijabs can dance without men in military gear shouting lies about them. Her prayer for the reign of mercy involves the undoing of White power, the loosening of racism’s grip on this country. Her song calls upon God to expose the deception of the proud, to unseat the arrogant from power—for God to scatter the wealth accumulated by means of racial capitalism.

And she rejoices at the downfall of oppressors. This summer Carolinians pulled down the confederate monument at the state capitol. When I saw the statue crash to the ground, I prayed for this to be a portent of Mary’s pronouncement. Months later, however, the president of the United States told a White supremacist group to “stand back and stand by,” to be ready when the president might need them for God knows what. Racism unleashed will be the legacy of Trump’s administration.

My politics are Marian. I join in her prayers to God the merciful, from generation to generation, who has promised joy to the descendants of Abraham, to the children of Sarah and Hagar, to Isaac and Ishmael—to every Mary, María, Miriam, and Maryam.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The politics of Mary.”