As monkeypox spreads, faith networks mobilize to fight stigma

Faith leaders from a range of religions are teaming up with World Health Organization officials to help prevent monkeypox as outbreaks of the disease occur across the globe.

Religions for Peace secretary-general Azza Karam said “theologies of compassion” that developed in response to HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and COVID-19 are shaping the plans being put in place to address the latest disease that is drawing their attention.

“There have been some very serious concerns about the fact that, like HIV, this is bringing back some of the stigma issues that people had thought they had overcome,” Karam said in an interview, given that “men having sex with men are also amongst the groups most likely to suffer it.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

RFP is an international coalition that includes six regional interreligious councils and more than 90 interreligious networks. Karam said leaders of the group’s organizations from Africa to the United Kingdom are sharing health advice and will recommend approaches that are approved by the WHO and informed by faith.

Those leaders are urging churches, synagogues, mosques, temples, and other faith communities to focus on helping people who are unwell, not judging how they may have gotten sick, she said.

“There is no shame in having any disease” is their mantra after dealing with past health crises, she said.

Scholars have long seen a connection between religious beliefs and shame-related stigma about HIV. A 2009 study of HIV and religion in Tanzania—surveying Catholic, Lutheran, and Pentecostal churchgoers—found a significant percentage believed that HIV was a divine punishment and that HIV-infected people had not followed God’s word.

But some religious leaders, including South African archbishop Desmond Tutu, who died last year, have sought to counter such stigma.

“l always say: Let us, as a church, speak out and speak up,” Tutu told Independent Catholic News in 2000. “HIV/AIDS is not God’s punishment for sin. You have got to say that quite firmly and categorically.”

At a webinar hosted July 13 by the WHO and RFP, scientific and religious experts highlighted the need to make more people familiar with the disease.

“Despite several countries reporting on monkeypox outbreak, many of us are not as yet familiar or aware of it as we need to be in order to take action,” Deepika Singh, RFP’s associate secretary-general and director of programs, said on the webinar.

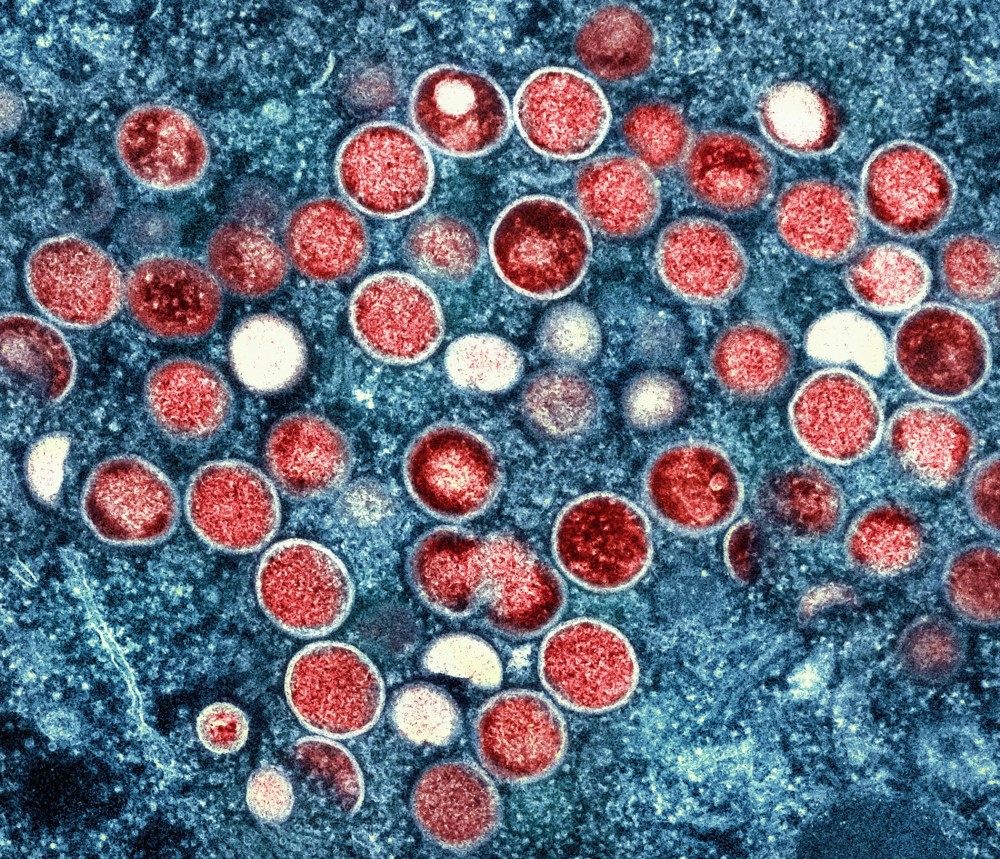

Monkeypox—so-called because it was initially found in a monkey in a Copenhagen research lab in 1958—was first seen in humans when a nine-month-old in the Congo contracted the disease in 1970.

By mid-July there were more than 10,000 human cases globally outside Africa, said Rosamund Lewis, the WHO’s technical lead for monkeypox, during the webinar. In Europe, 98 percent of confirmed cases were among men who had had sex with other men. Among suspected cases in the Congo Basin of Africa, two-thirds were men, 25 percent to 30 percent were women, and the rest were children. Worldwide, there are recent cases in more than 60 countries where monkeypox has not previously been detected.

The virus can include a rash or lesions that can remain infectious for two to four weeks, as well as a fever and sometimes painful swollen lymph nodes, said Lewis. Some sufferers require intensive care hospitalization.

She said some countries are beginning to obtain vaccines and other treatments but “it’s not something that happens overnight.”

“We have a very different presentation of the outbreak, or several outbreaks, which complicates the picture in terms of messaging and risk communications,” Lewis said. “We’re dealing with a major outbreak in men who have sex with men globally, much of which will be underreported, but at the same time, anyone can get monkeypox. It takes direct contact, skin-to-skin contact, face-to-face contact, but it’s not a sexually transmitted infection, or at least not exclusively.”

Andy Seale, an adviser to the WHO’s program on HIV, hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections, said lessons from COVID-19 and HIV especially could prove helpful for faith leaders addressing monkeypox as dozens of countries face it for the first time.

“Particularly the work from HIV that many of you have been involved in over the decades, support to people living with HIV and addressing stigma and discrimination,” Seale said, “that kind of experience is critical for how we start to really think about monkeypox.”

Francis Kuria, secretary-general of the African Council of Religious Leaders, a regional interreligious body of RFP, said officials of faith communities are prepared to work with health authorities in disseminating accurate information and appropriate messages.

“Religious leaders will be at hand to work with you to develop key messaging that can help contain any stigma that may arise,” said Kuria.

Seale said faith leaders can also be voices of calm, dispelling misinformation and offering practical assistance to people who may need to spend two to four weeks in isolation.

“We really need to be sure that we don’t unintentionally stereotype, stigmatize, blame, or shame any of these communities,” Seale said of those dealing with monkeypox. “If someone discloses that they’ve had monkeypox, I think we need to be careful that we react without being judgmental.”

Just as houses of worship have distributed food during the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, similar assistance may be needed, for example, by zero-hour contract workers who are not guaranteed any pay during isolation or others affected by cost-of-living increases.

“We have to recognize that isolation because of monkeypox is an additional challenge very similar to what we’re seeing around poverty and COVID-related problems,” he said. —Religion News Service