Robert Pattinson gives us the Batman we need

He carries the hesitant masculinity of Twilight’s Edward Cullen in his body.

I didn’t think I wanted another Batman movie. But it turns out that Matt Reeves’s The Batman—starring Robert Pattinson, who played Edward Cullen in the Twilight films—has the Batman we need.

I am sure many Batman fans and even Pattinson fans would like to pretend Twilight was an adolescent girl thing, something they can mock or at least ignore, if they even know who Edward Cullen is. I am fully aware Pattinson has taken many serious and interesting roles since his youthful days as a vampire heartthrob. But there are some roles that are so outsized in their cultural moment, they become ingrained in the actor’s very body. This does not mean that the actor cannot move beyond them or even radically depart from them. It does mean that there are bodily postures, physical gestures, and tones of voice that, when deployed, carry the long tail of the original performance. This is why, for example, when Robert De Niro sets his eyes just so as Jack Byrnes in Meet the Fockers, there is always a trace of Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver.

So it is with Robert Pattinson, who carries the hesitant masculinity of Edward Cullen in his body. Looking back a decade, Edward Cullen seems now like a tentative venture out of the death grip of toxic masculinity. He embodied a desired masculine power (he’s an immortal vampire after all) while remaining deeply wary of its uses and abuses, even when he used it tentatively to protect those he loved. Pattinson conveyed this hesitant masculinity through an almost rigidly controlled physicality—talking and even laughing through nearly clenched teeth, moving with deliberate slowness, holding his body in check even when angry, ecstatic, or sexually aroused.

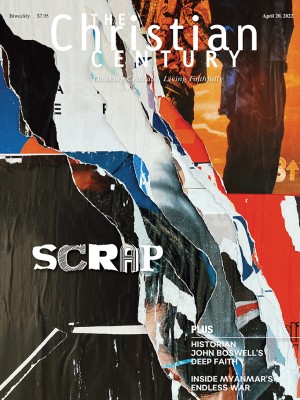

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This plays right into the erotic charge of chastity that made Twilight a pseudo-Christian feminist romance fantasy. But when Pattinson evokes this same physicality as Batman, he is reworking even broader scripts about masculinity and suffering heroics.

Batman has long embodied the basic ethos of the suffering hero: a hero who must be alienated from the society he protects and who pays for that alienation in emotional anguish. Paying this price is what allows the hero to engage in morally ambiguous (if not outright despicable) behavior without falling beyond the pale of justice. Batman exists on the edge of the law and outside the bounds of normal society. Without misunderstanding and alienation, he’d just be a rich guy playing violent vigilante.

The possibility that Batman is just a vigilante in a cape—and possibly psychotically deluded—hangs over most recent versions of the Caped Crusader, including this one. But no other Batman movie I’ve seen draws attention to just how strange and marginal Batman would really be, if taken seriously as a man in a bat suit fighting crime on his own.

In an early scene, Lt. James Gordon (Jeffrey Wright), one of the few honest cops in Gotham and the only one who believes Batman should be trusted, invites Batman to a crime scene. Other cops look disgusted and distrustful, ignoring or openly mocking him. This is where Pattinson’s hesitant masculinity starts to shine. He has the courage of his convictions—he is there in a rubber bat suit after all—but he is almost awkward, trying not to knock things over with his cape, holding his body in reserve, as though he’s embarrassed by his own potential strength and his need to mask it.

In the rare scenes in which Batman takes his mask off, Pattinson goes full Cullen, and his alter ego Bruce Wayne might as well be a vampire—pale and nocturnal, barely speaking, moving with such rigid control you can practically see the weight of the world sitting on his shoulders. These would be the full-blown tropes of the suffering hero—misunderstood, exiled to his lonely anguish even as he continues to battle against corruption—but the ambiguity and vulnerability Reeves draws out of that suffering find perfect expression in Pattinson’s hesitancy.

This ambiguity is most fully expressed in the final showdown with this movie’s archvillain, the Riddler, another alienated young man in a mask acting out his own version of justice who finds solace and support from other angry, disenfranchised White men on the internet. We are, of course, supposed to see the ironic parallels between this “bad” vigilantism and the “good” kind the Batman represents, and given recent real-world manifestations of vigilante justice, from the January 6 insurrection to the lynching of Ahmaud Arbery, this is a damning critique of where the suffering hero trope has gone in our society. In the usual arc of that trope, Batman would suffer increased alienation and exile so we could confidently claim him on the side of right.

Instead, Batman steps toward something else, something he names as hope. It remains to be seen if we can really have a Batman who doesn’t suffer, and this one is still pretty lonely by the end of the movie. But I went into the theater thinking I didn’t need another Batman and left excited to see what might come next, and this is not least because of Pattinson’s unique embodiment of heroic masculinity.

I am sure viewers can appreciate all of this without seeing Edward Cullen in Batman, and I am sure there are some Batman fans who would recoil from even trying to, because Batman’s suffering is what makes him a serious hero compared to the trivial fantasy of girls’ vampire romance. But our need for suffering heroes seems to be at least part of what Reeves is critiquing with his Batman, and engaging this critique might mean not being so serious that we can’t see the vampire in the bat.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The Batman we need.”