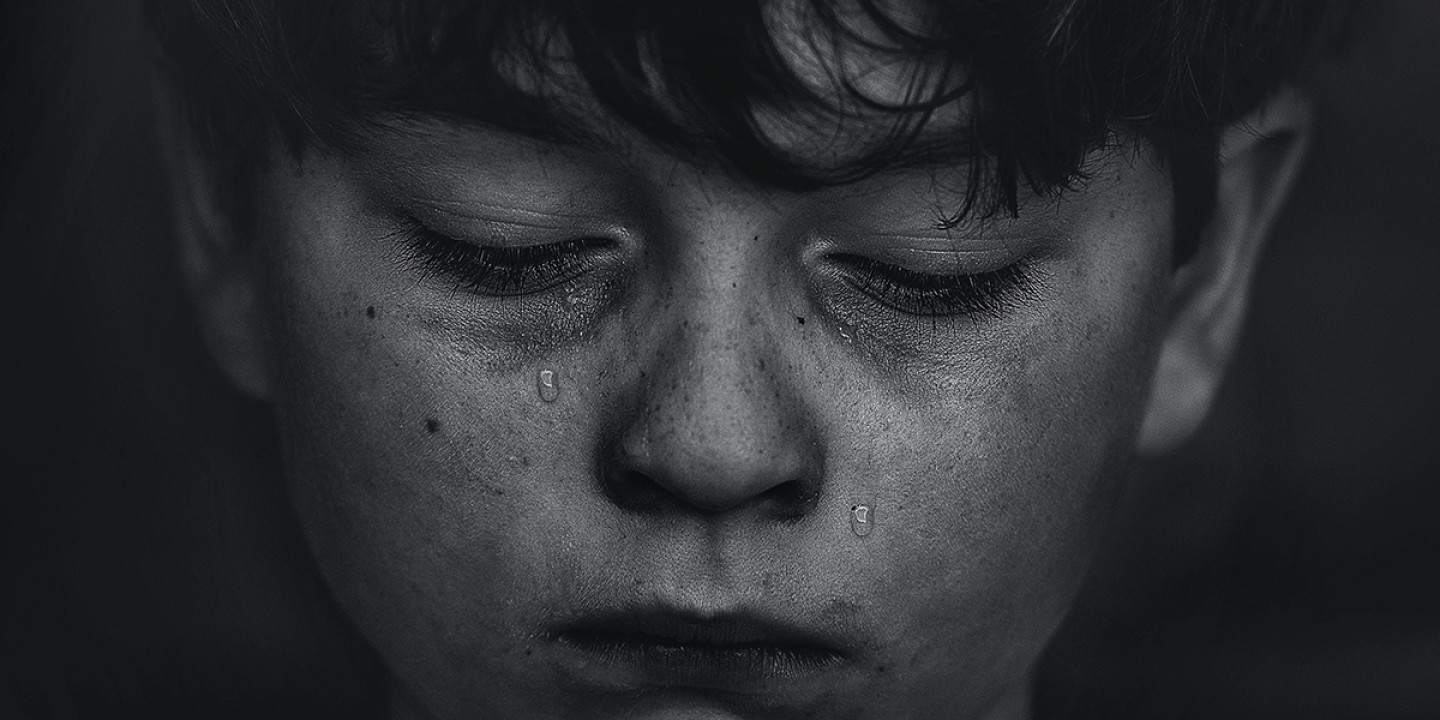

Tears are a gift from God

They put us in touch with essential things that we know to be dear or wrong.

Some memories never leave us. Climbing the final steps to the third floor of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, I entered the room with the shoes. Four thousand shoes in the exhibit, the leather of which still gives off a musty smell. We are the shoes, we are the last witnesses, a poem overhead reads, as if to deliver the final crescendo of the Final Solution.

A lone woman in the middle of the room was sobbing, her face in her hands. I felt helpless and must’ve looked helpless. I wasn’t going to walk over and put my arm around a complete stranger, especially a vulnerable woman crushed with grief. Instead, I stood awkwardly at a distance, listening to her cry. It wasn’t long before her pain caused me to start tearing up, too. In her company, I couldn’t find any reason to hold back emotion, especially in the presence of all those shoes. Those baby shoes!

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In the Bible, when Jesus weeps, it’s either in reaction to the grief of another or it’s his grieving disappointment over this broken world. When he sees Mary weeping over the death of her brother Lazarus, he begins to cry. When he weeps over Jerusalem, a city that didn’t seem to know what makes for peace, it is as if he were crying over human malpractice the world over.

In the early 19th century, essayist William Hazlitt suggested that weeping is an exclusively human behavior. A human “is the only animal that is struck with the difference between what things are, and what they ought to be.” Other animals can whimper and whine, but crying involves the production of tears. And humans are uniquely disposed to produce tears when life isn’t what they expect or imagine it to be.

This suggests that we cry for both happy and sad reasons. Nearly every time I visit my 94-year-old father, he gets teary-eyed at one point or another in the conversation as he assesses the fullness of his life. He seems constantly surprised by the beautiful relationships and experiences he’s enjoyed. Sometimes I think of Lou Gehrig tearing up during his “luckiest man on the face of the earth” speech.

Tears can be about deep heartache too, of course. Like St. Augustine grieving the death of his mother: “The tears . . . streamed down, and I let them flow as freely as they would, making of them a pillow for my heart. On them it rested.”

However they arrive, tears remain a biological gift from God. They put us in touch with essential things that we know to be dear or wrong. And those things have a way of taking up residence in our hearts, often drawing us inadvertently closer to God. Giving ourselves permission to cry is valuable, especially if we want to trust the psalmist that sowing in tears can reap shouts of joy.

When Desmond Tutu declared in an interview that his favorite prophet was Jeremiah, he went on to explain why. “[It’s] because Jeremiah cries a lot. I cry a lot too. I cry every day. But think how much God cries! We have a God who weeps . . . so I cry a lot and always have. But I also laugh a lot too.” With that, he let out his infectious laugh, which is exactly what Easter Christians are supposed to do.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “The gift of tears.”