The textures of a place

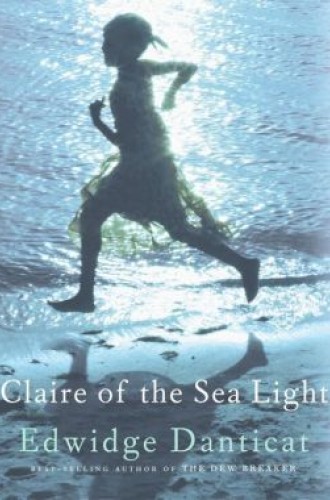

Reading Edwidge Danticat’s novel Claire of the Sea Light is like swimming through a gentle tide in a body of water known for riptides. The feeling that something invisible, fierce, and irreparable is just under the surface never quite leaves the corner of the reader’s mind.

The story traces relational ties in Ville Rose, a small coastal village town in Haiti. If the story itself were a rose, then Claire Limyè Lanmè would be the tightly curled center. Danticat starts from that center, touches the tightly overlapping petals of Claire’s family, and moves on slowly toward the edges of these connections with Claire—allowing the drama of each life touched upon to open, or close, without force.

Many things happen to the people in Claire’s story: love, birth, illness, murder, success, and indiscretion. But what stays with the reader most is the sense of a body of people in a particular place over generations—the textures of belonging, longing, betrayal, and folklore as palpable as wet salt in the air near the sea.

The story begins on Claire’s seventh birthday, when her father, Nozias, decides to give her to a wealthy textile saleswoman—a woman who had lost her own child after nursing Claire as a baby. The tale then spirals out to this woman, her work, her family, and their acquaintances; then to those families, until returning to Claire and her father and their moment of decision. The pretty but odd and extremely intuitive Claire, named after a beloved mother who died in childbirth, comes to embody something of Ville Rose itself: its beauty, strangeness, and vulnerability.

Despite all of these happenings, the book is almost more of a feeling than a plot. Throughout, a sense of place pervades—dense and translucent, soaked over time into the characters’ skin, breath, words, thoughts. The mountains and coastline of Ville Rose and Haiti feature in the story, like characters themselves, and might remind the reader at times of the best of this quality in Graham Greene. The tale itself mesmerizes—no story seems quite finished, the novel itself does not seem quite finished—but not necessarily as if it weren’t complete, only ellipsed.

This is the work of a restrained and expert storyteller. With remarkable elegance and insistence, Claire of the Sea Light shows us the human soul of a place. It invites us into what, in the end, feels less like a story and more like a collective memory, held in a clear and compassionate mind.