When daughters of fathers seek justice

Looking for God in the murkiness of human relationships.

My earliest feminist awakening occurred before sunrise one day when I set off “down south” with my lunch in tow. It was my first time to drive Dad’s John Deere tractor by myself and to prove the validity of my argument for this new job. “Girls are just as good as boys,” I had argued when I learned Dad paid my male cousin for his tractor driving and other work, while my hours spent toiling on the farm apparently didn’t warrant such pay.

Climbing the steps into the cab perched high above the ground, my heart pounded in my ears. I held my breath as the engine roared to life; my right hand nudging the throttle higher while my left foot slowly released the clutch. Turning to look over my shoulder, I carefully guided the plow as it gracefully spread out behind the tractor.

Those first nervous minutes slowly turned to hours and hours to days and days to a summer spent driving back and forth, around and around, until confidence in myself as a girl—a tractor-driving girl—took root.

My dad died in 2016. And while he wouldn’t have identified as a feminist, his willingness to be proven wrong was a pivotal point in the development of my feminist identity.

His openness to my demand for fairness reminds me of a remark Barbara Brown Taylor made in a recent interview. “I don’t have much confidence in sanctioned authorities anymore,” she said. “My confidence is in relationships.” Relationships, she goes on to say, “are the most reliable places I know to encounter God.” This is, of course, another way to speak of liberation.

Is it any wonder the Bible is full of stories about relationships of all kinds?

One, in particular, involves a father-daughter episode in which the father—Jephthah—makes a doubt-filled vow that comes back to haunt him. I’ve often read this as a tragic story, one that reinforces male privilege and patriarchy. Truth be told, my feminism has, at times, made not only this episode but much of the Bible a very difficult book for me to take seriously. Over the years, though, I’ve tried to be open to the possibility of surprise, even in these “texts of terror.”

Jephthah, one of the wayward judges in the book by that name, makes a vow that if God gives him victory in a crucial battle, in return he will sacrifice to God the first animal or person that greets him upon his return home. But what about his daughter?

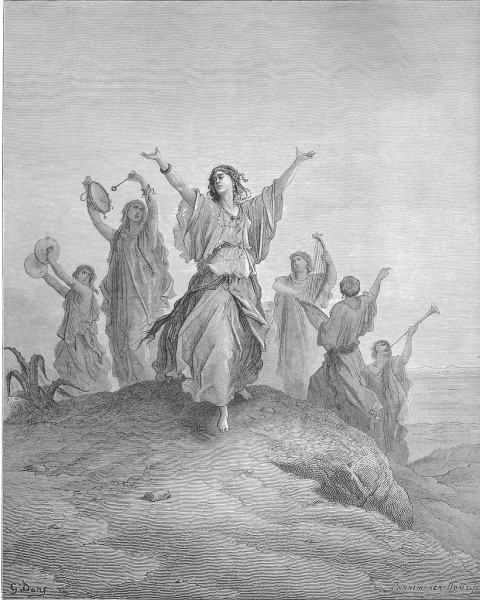

Upon learning of her fate, Jephthah’s daughter goes against cultural norms by withdrawing to the mountains to be with her friends (not her family). Her remaining days are spent in a community of women—a community beyond the reach of the narrator, who tries to fill in his story’s plot with his own assumptions. Readers might reasonably surmise that Jephthah’s daughter chooses to be with those who cherish her as a person, who know her well, and who also know what it was like to part of a society in which women are expendable.

Jephthah’s daughter and her friends create a safe space for women by withdrawing from their society for a time. Their action reminds me of feminist theologian Nelle Morton, who observed the experiences of women in the 1970s. In those meetings Morton witnessed what she called “hearing to speech,” an experience of deep, compassionate listening. According to Morton this attentiveness created “a hearing engaged in by the whole body that evokes speech—a new speech—a new creation.”

Jephthah’s daughter’s critique of Jephthah and his patriarchal system points to a transformative experience. Her countercultural initiative contrasts the difference between the father, who values his status more than his daughter’s life, and the daughter, who chooses an alternative path, one based in the power of community and relationship.

When the male narrator reports her lament that “she had never slept with a man,” he is clamoring for an explanation beyond his experience. But if this nameless woman were given a voice to speak, she might confirm what biblical scholar Danna Nolan Fewell says: that she knows men all too well, that her sorrow is not precipitated by her inability to fulfill patriarchal standards. Perhaps she isn’t even sad at all.

Jephthah’s daughter’s world has been dictated by men. But in the end, she knows how to make a different life. Whatever the limitations of her culture, she finds a way to respond on her own. What if, rather than feeling grief over the loss of a specific and socially dictated life, she experiences joy—the kind that comes from true liberation, from living in tune with one’s inner voice even when it contravenes social expectations? That our tendency is to judge a life by its length does not necessarily mean this is her perspective.

Leaving room for the possibility that Jephthah’s daughter chooses quality and meaning over longevity highlights the importance of communities of justice and liberation. It also reminds me to resist thinking such biblical narratives are so marred by patriarchy and sexism that there is nothing for feminists to find within them.

Of course, all of this is nothing more than imaginative possibility, and I have no more basis for conjecture than did the original narrator who reported this episode through his patriarchal lens. But if Barbara Brown Taylor is right—and I believe she is—then we need to keep looking for God in all of the complexity, murkiness, and paradoxes of human relationships.

Now, there is a stark difference between Jephthah’s daughter’s fate (however we characterize it) and my own experience of sexism as a child. The power of patriarchy in that time and place far exceeded its subtler influence in this one.

Nevertheless, like Jephthah’s daughter I learned about liberation by resisting my father. Sure, it would have been easier if he had treated me equally from the start, but in his responsiveness to my questioning, I learned an important lesson. Whether as a young girl learning to drive a tractor or a mid-life woman who misses her dad, I know that seeking justice one person at a time is life-changing.