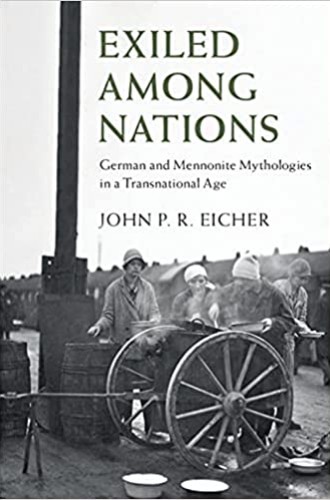

When Mennonites were settlers

John Eicher’s history exposes European Mennonite complicity in Native dispossession.

I’ve wandered through church traditions the way my family has migrated across the geography of the Americas. My mother came from Costa Rica, my father from Colombia. My sister and I were born in Los Angeles; then we moved to Tucson, Arizona. Now I live in Durham, North Carolina, where I make my ecclesial home in the Mennonite tradition. After a migration from the Roman Catholicism of my birth, through charismatic and Pentecostal versions of evangelicalism, I wandered into a Mennonite congregation in 2004. I’ve been a member ever since.

I’ve found my belonging within a Christian tradition born and reborn in the travails of migration, of survival from persecutions—church cultures revised with every resettlement, theological identities re-formed with every relocation. The Mennonite faith is a wandering tradition with a diasporic sense of peoplehood—a disposition similar to my family story, crisscrossed with departures and arrivals, always making a home among new neighbors. To seek the peace of the city, of the land, of people and place, Jeremiah’s vision guides Mennonite sensibilities for political belonging that aims to navigate a Christian existence in the world but not of the world, in the polis but not of the polis. To join this way of being Christian in the United States has been a kind of homecoming for my misfit identity as a child of immigrants.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In Exiled among Nations, John P. R. Eicher recounts the plight of Mennonites who left Russia at the end of the 19th century—some as refugees, others as voluntary migrants—and spent the next century wandering through Germany, Canada, and Paraguay in search of hospitality. Eicher tracks their theological disagreements and cultural tensions as they attempted to make a life among strangers.

He also describes how Mennonites who had already found a home in North America in the early 17th century discerned their kinship with this more recent wave of migrants. Church members in Canada and the United States formed a binational humanitarian organization, the Mennonite Central Committee, in part to broker the safe passage of these émigrés and to assist them in resettlement—and later, to assimilate these newer arrivals into a particular “new world” Christian identity. A transnational Mennonite community of faith emerged within the context of burgeoning European and American nationalisms.

These migrations and negotiations happened within the context of “global forces of nationalism, citizenship, ethnicity, and displacement,” Eicher explains. “As the twentieth century unfolded, there were millions of individuals who were voluntarily or coercively relocated because they did not fit a particular government’s prescribed national, racial, or class demographics.” In other words, this particular Mennonite story resembles the stories of other groups who had to forge their diasporic identities on trains and ships, re-forming their faith among strangers in strange lands.

Harold S. Bender, the esteemed North American Mennonite leader, likened the situation of these Mennonnites to that of Jews in diaspora. “We old Mennonites are somewhat like the Jews,” Bender commented. “We are almost a race, as well as a Church.” Eicher notes the resemblance between Bender’s call for North American Mennonites to provide material support for European Mennonites in diaspora and the concurrent efforts of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, established in 1914, to support the formation of Jewish settlements “from the plains of northern Crimea to the jungles of the Dominican Republic.”

The “Mennonite Question” emerged as part of the invention of the nation-state in Europe. “Nationalist paradigms and fantastic solutions for territorial insecurities were not only the domain of governments who wished to solve a ‘German Question’ or ‘Jewish Question’ during the interwar years,” Eicher observes, “but had seeped into the organizational ideals of a wide range of religious groups.”

In 1930, the second Mennonite World Conference was convened in the Free City of Danzig (now part of Poland), mainly to deliberate on how to support and relate to Russian Mennonites who relocated to South America, as well as to those who remained in the Soviet Union. Bender briefed the crowd of representatives from Mennonite mutual aid agencies in Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, and the United States regarding the settlements in Paraguay. “The Mennoniten-Völklein [Mennonite subnation] can continue to exist in Paraguay with its culture and faith under the most favorable conditions,” he said, because “there exists no culture in that area at all.”

This vision echoed the Zionist discourse of Bender’s era, in which Christian and Jewish Europeans fantasized about “a land without a people for a people without a land.” Eicher summarizes this mid-20th-century dream for a global federation of Mennonite enclaves: “Bender suggests that Mennonites in North America and Europe should initiate an almost Zionist experiment to solve the problem of Mennonite persecution by obtaining territory that was not yet completely under the jurisdiction of a nation state—territory that possessed ‘no culture.’”

The search for the areas at the periphery of the modern state’s control is a theme that Eicher tracks throughout 20th-century Mennonite migrations. “Mennonites routinely sought out states with weak or amorphous borders where they could establish agrarian communities that were relatively free from state control,” he observes. These promised lands, obviously, were not in fact absent of people. Mennonite relocations served the modern nation-state’s quest to displace indigenous peoples.

The settlement that arrived in the Paraguayan borderlands with Bolivia in the 1920s consisted of descendants of German Mennonites who had first displaced the Nogaitsi people in the Russian steppe in 1789 and then the Métis and Cree peoples of the Canadian Prairies in the late 19th century. “On three continents in less than 150 years,” Eicher summarizes, “Mennonites sought indigenous lands confiscated by state authorities.” Modern states harnessed these migrations for their own colonial schemes to displace indigenous peoples and convert wilderness into farmland. The government of Paraguay welcomed Mennonites in the hinterlands “as Manifest Destiny on the cheap.”

While Bender and the Mennonite Central Committee tried to assimilate these 20th-century European migrants into a transnational peoplehood, Nazi propagandists tried to convert them into outposts of the “Greater German Reich” in the Americas. One Paraguayan colony in particular—the Fernheim Colony—maintained contact with the Association for German Cultural Relations Abroad (VDA), which during the Nazi era became a program to cultivate allegiance to the fatherland among Germanic peoples throughout the world. Eicher also recounts the work of ethnic Mennonites who had remained in Germany and drifted into Nazism with the rest of society to serve as emissaries of the Reich to the Paraguayan settlements. One such visitor in 1934 noted with glee that some in the Fernheim community would greet each other with “Heil Hitler!”

When the VDA sent a representative to observe the Germanness of the Mennonites in Paraguay, the envoy registered his disappointment. In his report he characterized them as too Jewish: “Jewish history dominates the Mennonites to the last detail and by giving their people Jewish names, they outwardly align themselves with the Jewish people.” Apparently, their biblically saturated culture wasn’t a good fit for the Reich’s fantasies of a transnational Aryanism, especially with all the Mennonite boys and men named Abraham.

With each century, another wave of migration crashes across the Americas, reconfiguring the religious landscape. Eicher tells the story of one group caught in the push and pull of nationalisms in formation in Europe and the Americas.

But this is not only a Mennonite story, and patterns of relocation aren’t unique to the 20th century. Church traditions and theological discourses in North America didn’t drop from the sky and land in downtown cathedrals and prairie congregations willy-nilly. The deposit of faith doesn’t parachute from heaven every week just in time for the call to worship. Instead, every theology is a contextual theology. Cultural histories accompany the gospel. Bankers and politicians helped negotiate who would worship where for reasons the faithful would rather ignore.

Mennonites don’t have the problem of owning a Wall Street church with a $6 billion endowment. But we do have the majority of our congregations in rural America, on land that was stolen from indigenous peoples. Eicher’s history exposes European Mennonite complicity in Native dispossession.

Anabaptist suspicions of governmental control guided communities of faith to the edges of the state’s reach. Now, in the wake of such histories, the institutional work of repentance and repair has already begun. In the late 20th century, church leader Menno Wiebe developed the relationships and vision for what became the Indigenous-Settler Relations office within Mennonite Church Canada. In the United States, Native-led congregations have been part of the denomination through the Mennonite Indian Leaders Council and the Native Mennonite Ministries constituency group. Our commitment to the peace of Christ is at stake in our confrontation with the legacies of colonial violence. In the Americas, truthful articulations of the Christian faith should involve historical accounts like Eicher’s.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Mennonite settlers.”