What I knew about Jane Goodall: she was the woman who lived in Africa with apes. I could conjure an image of her from pictures I’d seen—slender, attentive, crouched with binoculars, hair pulled into a ponytail. I didn’t remember, if I’d ever known, the seismic shift in primate biology occasioned by her discovery that chimpanzees use tools. Once, in a tense family Trivial Pursuit battle, my middle-aged brain took several minutes of silent concentration to locate the mental file with her name on it. “I know her name has a g,” I said.

Then I caught the last few minutes of an interview with her, timed to promote the 2020 National Geographic documentary Jane Goodall: The Hope. A caller asked Goodall what brings her joy. She answered, “It's being out in nature, and it doesn’t have to be the forest with chimpanzees, although that’s my very most favorite. But somewhere out in nature, preferably alone.” In that moment, I felt like I’d discovered a new friend, reminding me in a gentle British accent that since the beginning of this pandemic one occupation has given me more joy than any other: sitting on the back patio, watching the animals, preferably alone.

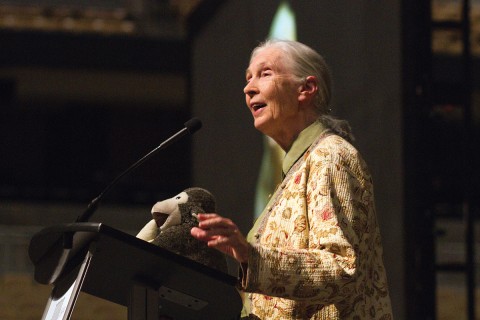

When the interview ended, I headed to the den in our basement and watched the documentary. I learned even more of what I didn’t know about Goodall, not least that my own observing nature has nothing in common with her early immersion in the forest. I learned that she’s a visionary and entrepreneur who now rarely gets to do what brings her joy, grasped as she was by a new vocation, a new call—call, the only word that captures the depth of her dedication and warrants its costs. “I’m always traveling, trying to save the world,” she says. “A bit of a tough job.”