What does ‘Christian nationalism’ even mean?

Could it really be all the different things people say it is?

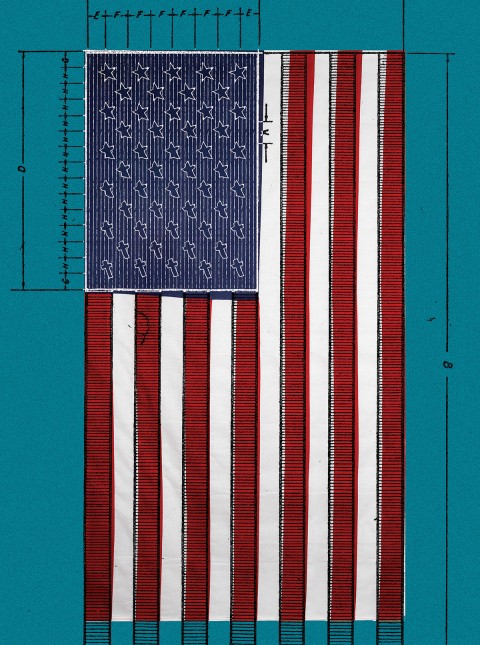

(Century illustration)

Fear over Christian nationalism is running rampant, showing up everywhere from books and podcasts about the January 6 insurrection to Sunday sermons about idolatry. But the way we talk about Christian nationalism comes with all kinds of problems. Until we resolve these problems, all this fear about Christian nationalism might amount to so much fearmongering.

First, what is Christian nationalism? Sometimes it’s presented as an ideology and sometimes as a conspiracy. Sometimes it identifies a specific group of people, other times a diffuse set of associations. Some see Christian nationalists as aggrieved Americans on the losing side of history; others see them as secretly pulling the strings of American politics. Christian nationalists might have arrived on the scene just in time to elect Donald Trump, or maybe they’ve been here all along. Their aspirations may be theocratic or libertarian. Some Christian nationalists consider Trump the second coming of Christ, while others see him as a regrettable means to an end. Lots of Christian nationalists are White racists, yet some of them are not even White. Oftentimes Christian nationalists are described as evangelicals, which, it so happens, comes with as many definitions as Christian nationalism.

The more things Christian nationalists are, the scarier they sound. Yet if Christian nationalists are all of these things, then they are none of them. Concepts that try to do everything end up doing nothing.

Second, lots of the literature on Christian nationalism deals in circular reasoning. We don’t easily see this because it often comes dressed in what looks like data. But as sociologists Jesse Smith and Gary Adler show in “What Isn’t Christian Nationalism?” it’s data that gets paraded out in tautological, question-begging ways.

One common rhetorical strategy goes something like this: “Christian nationalists are those who believe that God established America as God’s shining city on a hill.” What follows is usually an alarming data point such as, “Studies show that Christian nationalism is positively associated with denying anti-Black violence.”

This sounds well and good—until one thinks about it. Doesn’t the idea of God establishing America as a city on a hill already include within it a denial of anti-Black violence, namely, the erasure of American chattel slavery? And doesn’t denying anti-Black violence often come with the downplaying of slavery? In fact, isn’t the one simply an instance of the other? If so, then the data point’s conclusion is already entailed in its premise, such that it says little while implying a lot— something to the tune of “Christian nationalism caused the January 6 insurrection” when in reality the logic amounts to “Christian nationalism caused Christian nationalism.”

Third, those who worry a lot about Christian nationalism seem surprisingly unthoughtful about a central issue it raises: the question of how the church should relate to the state. This question can be approached as one for political theorists, who might wonder, for example, where the state ends and the church begins. It can be approached from the perspective of Christian ethics, which might wrestle with Christian citizens’ obligations to Caesar and to God. These are enormously complicated questions, and over the course of the millennia they have been debated we’ve seen many different answers. Yet people worried about Christian nationalism often talk about it as if there is but one settled answer to the question, and Christian nationalists are those on the wrong side of it.

Concepts that try to do everything end up doing nothing.

Until we come to some resolution on these problems, it will be hard not to see those scaring us about Christian nationalism as fearmongers, and unself-aware ones at that: isn’t fearmongering one of the things we worry most about with Christian nationalists? Aren’t we right to distrust their political dog-whistling, the way they scream “CRT!” or “fake news!” at everything they don’t like? But how is regularly using a term as undefined and question-begging as “Christian nationalism” any different? We might answer, “Well, the difference is they’re Christian nationalists and we’re not.” That answer speaks for itself.

It also reveals the hypocrisy of it all. Indiscriminately using a term that means everything and nothing licenses a view of one’s political rivals as unsophisticated, devoid of difference and diversity, simpletons of one mind, flat to the point of banality, reducible to one thing—something like January 6. Perhaps that’s really the reason for using the term so loosely: while it does little conceptually, it does so much politically—generating, as Brad East observes, little light but lots of heat.

And so with the rhetorical benefits that come with the other two problems. We question-beg so as not to have to come to any conclusions we didn’t start with, dealing in tautologies so that we can avoid anything that might make us think. We presume ourselves in possession of the only answer regarding church and state, presupposing we must be right because we’re us and they must be wrong because they’re them. And not just wrong but irremediably wrong, Christian nationalist wrong.

Many on the right, like many on the left, have suffered at the hands of a nation that cares more for profit than for people. To deny that suffering by disparaging people as Christian nationalists lends credence to something they might already believe: that America not only doesn’t care about them but doesn’t even see them. Calling them Christian nationalists will not help them feel seen. It might, however, lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy where the unseen mobilize along sectarian lines marked out by dog-whistling. We might rather save our fear for that.