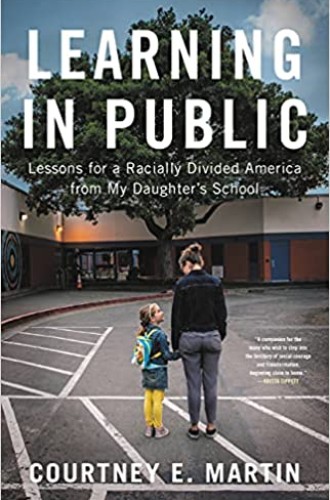

Addressing educational inequity means loving other people’s children

Courtney Martin invites progressive parents to reckon with racial justice.

Last year, soon after George Floyd’s murder, women in my almost all-White Anglican church in the Chicago suburbs read James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree. I was one of two Asian American women in the group. When we started asking what it really means to act as if Black lives matter as much as White lives, the conversation got real. Someone suggested diverting resources from our suburban schools to struggling city schools. In the thick silences, we reckoned with the reality that racial justice might mean our kids don’t always get the best.

This reckoning is the premise of Courtney Martin’s new book. Martin is a journalist who moved from Brooklyn, New York, to Oakland, California, when she was pregnant with her first child, who is now a second-grader. Oakland Unified School District’s open enrollment policy allows families to apply to attend schools outside of their neighborhood, effectively creating a system where the most informed and advantaged parents can opt out of failing neighborhood schools and concentrate their resources in the better-ranked schools.

When her daughter approached school age, Martin anguished over the enrollment decision, along with many of Oakland’s White and economically advantaged parents (and she includes Asian American parents in this category). It boils down to an apparent trade-off between the (usually) White mom’s progressive politics—which would entail sending her child to the neighborhood school—and her responsibility as a parent, “which would necessitate using her privilege to get her kid into the ‘best’ school she can possibly access,” Martin writes.