Bearing the scars

Years ago, at a barbecue in Argentina, I realized I was the only person present who wasn’t a survivor of torture.

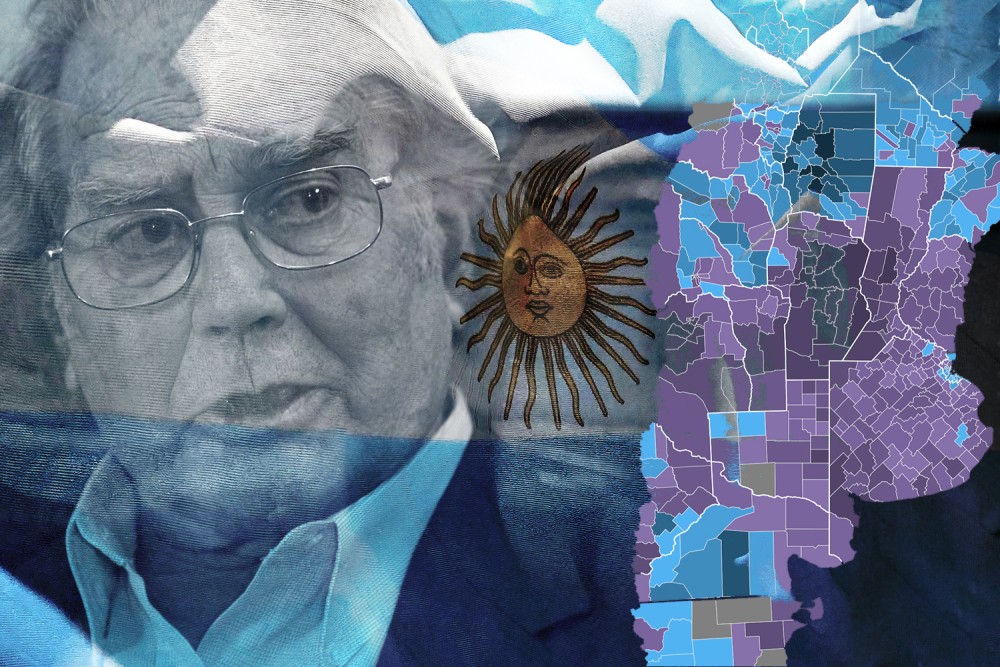

Adolfo Pérez Esquivel of Servicio Paz y Justicia in Argentina (Source photo: Romina Icaza / Asamblea Nacional)

The recent election of Javier Milei as president of Argentina—with his telling slogan “Make Argentina Great Again!”—brought back memories of studying and living there. I was there during the Dirty War in the 1970s and early ’80s, which pitted a military dictatorship against the Argentinian people, leading to the kidnapping and death of some 30,000 people, many of whom were tortured before being dropped from planes into the ocean. Milei has his own version of events favorable to the dictatorship.

In addition to attending seminary, I volunteered with a human rights group, Servicio Paz y Justicia. The leader of the organization, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, invited me to a small gathering at his home. When I arrived, it seemed like a typical Argentinian barbecue. The air was filled with the rich smoky scent of chorizo, beef, and chicken on the grill. A makeshift table had been set up in the garden under orange and lemon trees. A few people were strumming guitars, and there was singing, laughter, and hugs as others arrived.

As the afternoon wore on, I became aware that I was the only person at the party who was not a survivor of torture. Adolfo himself had been tortured and held without trial for over a year before his release. It was a warm day, and while I tried not to stare at bared arms and legs, some torture scars were visible, ugly signs of the worst that humans do to each other. The scars held a strange beauty as well, emblems of commitment to the struggle for human rights regardless of the consequences.