Being church while the neighborhood burns

“There’s a fire that cannot be extinguished except by justice.”

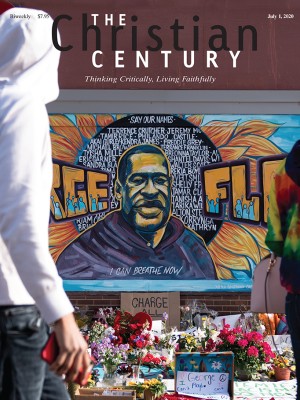

Ingrid C. A. Rasmussen and Angela Khabeb are pastors at Holy Trinity Lutheran Church in south Minneapolis. When protests, violence, and property destruction erupted after the killing of George Floyd by a police officer, Holy Trinity quickly emerged as an organizational center for volunteers, medics, and wounded protesters.

Tell us about your church and its neighborhood. How long has Holy Trinity been serving the community and in what ways?

Rasmussen: Holy Trinity is 116 years old, and the church’s sense of connectedness to the local community is a central piece of its mission and identity. The Longfellow neighborhood is quite mixed in terms of income and race, and it’s long been a center for various immigrant communities. Lake Street is culturally rich and diverse: the Scandinavian gift shop stands beside a popular Latino grocery store.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The church has a relationship with two affordable housing facilities that were built on our property. We serve about 150 residents, and a lot of them are in property-based Section 8 housing. That longstanding relationship is particularly important in these days when the social underpinnings of the community have been shaken.

Khabeb: Our church has such deep roots in this community and such a reputation for justice work. Our block is practically decimated, but the church is largely untouched, and the affordable housing is also untouched. That’s a real testimony to our commitment to being the church in the neighborhood.

Your church has been doing a lot to support protesters and neighbors. Tell us about the activities you’ve been involved in since George Floyd was killed.

Khabeb: When George Floyd was publicly executed at the corner of 38th and Chicago, and then the protests arose, and then they began generating injuries, we hosted a medic station to receive people who’d been wounded by tear gas or rubber bullets. The Indian restaurant across the alley from us, Gandhi Mahal, started the original medical site. But the building next to it caught fire and they needed to move, so they approached Holy Trinity and we opened our doors. We had a medic station here for two nights.

One of those nights there was no power, so we got out flashlights and candles and we were able to provide sanctuary. Some people just needed to come in and wash their hands or go to the bathroom. Others just needed to sit and think. They couldn’t believe what had just happened.

I saw a man running by shouting, “My eyes, my eyes!” So I handed him a gallon of milk. He said, “What, should I drink it?” He just couldn’t get his head around what had happened. He had no idea what to do.

As the church’s response to the crisis became known, we began receiving incredible amounts of donations: food, diapers, toiletries, plywood for boarding up broken windows, cleaning supplies, tools. We’re trying to get these donations in and then back out to the community as quickly as possible.

Was it hard to mobilize volunteers during a pandemic?

Rasmussen: No, but it has limited which subgroups of the congregation can do the work. In another situation I think we might have more of our seniors volunteering. Right now we are supported by young adults who are doing the bulk of the work, those at lower risk for COVID-19.

Khabeb: Oh, I wasn’t even thinking about COVID. When you said pandemic, I thought you meant the other pandemic: poverty and racism. I guess COVID isn’t even on my radar anymore. For months, it was painful to watch the news and see how the virus has been disproportionately killing black people. Now it feels like we’re saying, “Not now, COVID. We’re busy over here.”

As the peaceful protests were joined by instances of property damage and looting, as well as by armed protesters who didn’t necessarily share the original protesters’ goals, how has your church’s response to the crisis changed?

Khabeb: There are different kinds of fires. There are white nationalists who are armed and want to incite a race war. Then there’s a fire that cannot be extinguished except by justice.

Frederick Douglass said, “Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob, and degrade them, neither persons nor properties will be safe.” The connection between people and property is important. Slave patrols were the root of our modern-day police forces. Throughout American history, property has consistently mattered more than black lives.

This morning I saw that our neighborhood store has armed people outside to protect it. When that store opens up, I’m going to go inside and ask the owners, “What in here is worth my life? Show me one thing in this store that’s worth killing me for.”

I’m overjoyed that we can open up our doors and give away food and supplies and diapers to people. And there are so many volunteers out in the streets now, sweeping and cleaning and removing graffiti. But if we could put even a fraction of that energy into arresting those three remaining cops, that is what we should be doing. We need all these other things too, but calling those three cops to accountability is the work of the church.

Rasmussen: The only thing I’d add is that our church—and probably many others in our community—knows how to distinguish what arises out of righteous anger from what arises out of hatred and exclusion. And when a movement that arises out of righteous anger is hijacked by hatred, we necessarily change course in how we respond.

You both posted Facebook Live videos in the aftermath of the violence in your church’s neighborhood. Ingrid, you showed a piece of #BLM graffiti on the church property and said, “maybe we’ll keep that one.” Angela, you suggested that all of the white people scrubbing graffiti off of buildings might be putting their energy into the wrong thing. What do you think people’s responses to the graffiti represent?

Khabeb: At the most basic level, people are saying, “Let’s clean it up, this is unsightly.” People want to be able to physically do something. We’ve been trapped in our homes, we’ve got cabin fever, and we want to do something with our bodies outside. And graffiti makes people uncomfortable.

But there is a time for lament, and we can sit in this uncomfortable space for a while. Because there is no back to normal. Even with COVID, we were never going to get back to normal. And now our neighborhood is in ashes.

Rasmussen: Just across the alley from us is MIGIZI, an indigenous youth empowerment and news organization that moved in a year ago. Somebody tagged it with the saying, “This is not destruction. This is the beginning of new life.” I think that is one way to look at the messages that we’re seeing in recent days.

If erasing these messages isn’t the most urgent priority, where should people of faith— especially white people of faith—place their emphasis instead?

Khabeb: Dismantle white supremacy in our congregations and in our hearts. For each congregation, that process may begin in a different place. Wherever you’re starting, you’ve got the world at your fingertips. You can see speeches from great intellectuals, read books, attend anti-racism training—and you can do all of this online. Two books I’d recommend are Mai-Ahn Le Tran’s Reset the Heart: Unlearning Violence, Relearning Hope and Resmaa Menakem’s My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies.

Rasmussen: In predominantly white communities, it’s really important to name the fact that dismantling white supremacy is the work of white people. We need to hold each other accountable rather than expecting people of color and indigenous people to do the work for us.

Khabeb: Another thing people of faith can do is put pressure on Attorney General Keith Ellison’s office to bring charges against the other police officers involved in George Floyd’s death. If we rob a bank together and I kill someone in the process, all of us are charged with murder—even if one of you stays in the getaway car and the other one stays outside standing watch. Those three other cops need to be arrested.

What does the fact that they haven’t been arrested say to the community?

Khabeb: Every day that those three police officers are not arrested is a day that I know my humanity is not valued. Not just me, but my husband and my kids too: we are not fully human. It’s painful. It’s important to say his name, George Floyd, but if you search for the names of other black people who have died at the hands of police, you’ll see that the list just goes on and on.

Rasmussen: Even in our own community, there are other names. Philando Castile, Jamar Clark. This is not the first blatant instance of police brutality in the Twin Cities.

Khabeb: Isak Aden. That was the first protest I went to when I moved here. And I still weep over Emmett Till, and he was murdered before I was even born. We weep, but at no point are we healed from any of this. Our community still hasn’t healed from slavery.

A few months after people began sheltering in place due to COVID, white people came out and said, “we will not be oppressed like this.” They showed up at their government buildings with long guns and lined up and got in the cops’ faces. They had been oppressed for 10 damn weeks. Black people have been oppressed for 400 years.

Rasmussen: I think you’re being generous with your use of the word oppressed to describe white people who were staying in their own homes.

In your Facebook videos, you each talk about Langston Hughes’s poem “A Dream Deferred.” What are your dreams for your neighborhood?

Khabeb: Dreams don’t come easily for me. I memorized that Langston Hughes poem when I was in elementary school. But since then, the disappointment has been too great; it’s been too heartbreaking. There is such a nimble balance between hope and reality.

Maybe my dream for the community is that kids can be whole. Kids are feeling this, even if they don’t have the language to express it. When we walked into the neighborhood yesterday, one of my kids asked me, “Mom, is the whole city burnt down?” I guess I should have made it clear that this isn’t everywhere. On the news, it looks like everything is burning.

As you negotiate this nimble balance between hope and reality, how do you speak about hope to your congregation?

Khabeb: I think of the Negro national anthem, “Lift Every Voice And Sing,” which talks about “the days when hope unborn has died.” The Bible tells us that we do have a hope, and hope makes us not ashamed. So I try to cling to that. It’s the kind of fleeting hope that’s hard to get your hands around, and it’s out there somewhere. Kids have hope, though.

What keeps you going in the face of overwhelming problems and encroaching despair? How are you caring for your own spirits?

Rasmussen: Yesterday a big burly guy came up to me after dropping off about 1,000 boards of plywood. He saw that I’m eight months pregnant, and he said to me, “may that child never witness what we have witnessed in the last days.” I think there is something about wanting to participate in building a world where my kids experience something different, and even more than that, where Angela’s kids live in a new reality. There’s something about building a new reality that is powerful and keeps me going in these days.

Khabeb: I’m marveling now at a shift that’s happening inside of me. I did not see it coming, and I could not have predicted it. As a child I was raised to be polite, to put things in the most positive light possible, and above all not to hurt people’s feelings. But I’ve been reading Frederick Douglass, who was criticized for being too blunt. And I’ve been thinking about Malcolm X, who said, “It’s not time to compromise. Say what it is.” Something has switched inside of me, something has turned, and I’m not going to compromise. Especially when my humanity is at stake. What point is there in me being polite when you could snuff my life out? Politeness has left the building.

Rasmussen: Polite doesn’t always equal loving.

Any other advice for people of faith trying to negotiate this crisis?

Rasmussen: As I hear news stations talking about what’s happening in Minneapolis, I’ve really started thinking about how much words matter. When we call this a riot, that word has certain undertones. As people of faith, we might rethink the ways we’re framing what’s happening around us. Within our local clergy groups, clergy of color have raised up alternative ways to talk about this, like social unrest or uprising, in a way that decriminalizes the righteous anger that the church should be supporting right now.

Khabeb: That’s helpful. And I think that also applies to the way we talk about Jesus. Let’s call it “a state-sponsored public execution,” because that’s what it was. Let’s call Jesus a “death row inmate,” because that’s what he was. And then in the future when people hear those same words describing someone, perhaps they can connect it to Jesus.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “A church’s neighborhood on fire.”