Choosing solidarity with God

In a sense, I am asking my parishioners the same thing John Wesley asked: Are you going on?

A Lampedusa Cross, made from the wreckage of boats transporting migrants to Europe from North Africa (Photo by Doyle of London / Creative Commons)

We do a lot of denouncing and pronouncing. Churches—other Christians—are just so embarrassing to us. Maybe it’s time for a different tone of voice. Announcing, maybe.

Recently I preached at a weeknight service at my own church. Some while ago we’d earmarked it as an occasion to induct eight new members of our Nazareth Community. Each member takes an annual vow of silence (observed three times a week), sacrament, study, sabbath, sharing, service, and staying with. We started it in 2018. It now has 88 members. It’s the most diverse community—in race, class, sexuality, ability, and much else—I’ve yet encountered. Its online sister, the Companions of Nazareth, has 135 members.

Then one of my clergy colleagues decided she wanted her baby baptized at the same service. Fine. Then a new member of our congregation said he wanted to be baptized too. This was another matter. He is from the Middle East. Turns out it’s tough to be gay in the Middle East. We have to be careful with a lot of our congregation’s members who’ve fled to this country: careful they don’t appear on the livestream video, careful we don’t use their names in public. It’s our moment of encounter with the early church and the catacombs.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Our catechumen gave a testimony at the start of the service. He spoke of coming to the United Kingdom. Of finding himself in a maze of deception, denial, and despair greater than that which led him to leave his country of birth. But also of meeting his partner. And then of joining a gardening group, where he met a Japanese woman who said, “I go to St. Martin’s,” and issued an invitation. He came. It was Palm Sunday. He saw the dramatic portrayal of Christ’s Passion—a man surrounded by love and then betrayed, handed over to hostile authorities, stripped, beaten, ostracized, exposed to the elements, and stretched out in agony. Never giving in to hate or recrimination yet knowing utter abandonment.

Seeing this, he had a flash of realization: “This is me. This story is my story. This man is the person I want to follow the rest of my days.” He joined the journey through Holy Week and at Easter discovered this is not the end of the story—of God’s or of his. Standing in line to receive his citizenship ten weeks later, he knew there was a kind of belonging deeper and more significant than becoming British. It was belonging to the body of Christ—the body of that one whose body he’d seen on Palm Sunday beaten, bruised, buried. The congregation clapped, like a 12-step group applauding when one member has the courage to say, “I’m an addict.” The applause was of solidarity but also awe.

It was hard not to see the waters of baptism representing not just the Red Sea and the Jordan River but the dangerous waters of the English Channel by which so many asylum seekers have reached the UK—just as those baptismal waters evoked the Ohio River for so many Black Americans in centuries past. Yet beside this catechumen was a baby girl, longed for by her parents and the community around them, the visible epitome of what it means to be precious, honored, and loved. The wonder was that both were children of God and both were loved as if they were the only one.

Because one of the baby girl’s parents is a community organizer, I preached about solidarity, citing the example of the Polish priest Jerzy Popiełuszko, whose state murder in 1984 presaged a funeral attended by 250,000 people and the beginning of the end not just for the Polish regime but for Eastern European communism as a whole. Lo and behold, it turned out one of the baby girl’s godparents is the daughter of one of Lech Wałęsa’s Solidarity trade union leaders, who fled Poland around the same time. At Jesus’ baptism, I said, we see that God is wholly immersed in us, and we are asked if we are wholly immersed in God. That’s what solidarity entails.

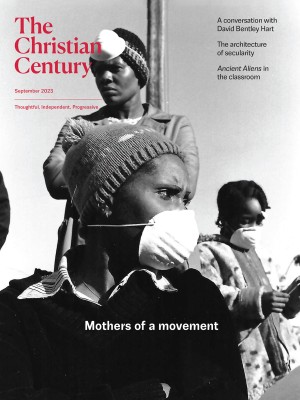

It is my great privilege to be protector of the Nazareth Community, which means I get to place around the necks of newly inducted members a spindly cross made out of the wood of a boat that carried asylum seekers to the Italian island of Lampedusa, in a notorious 2013 incident in which 155 were saved but 359 died. (The original, much larger cross stands in the British Museum.) Whenever I do this, I think of John Wesley’s words, “Are you going on?” I picture the disciples who stayed at the edge of Gethsemane and those who went on with Jesus into the heart of the garden.

To join the Nazareth Community is to declare that you’re going on. Before me are the bowed heads of such diverse and deep people. And on this occasion the same Middle Eastern man who’d been baptized 20 minutes earlier was one of those who bowed his head. Not for him were faith and discipleship ever to be separated.

But the best was yet to come. A child of the pandemic, not content with beholding these mysteries, discovered a church member had an electric wheelchair. He spent the eucharistic prayer bouncing on her knee and testing the sounds coming from the various buttons by her right wrist. As she moved her chair forward to receive the sacrament, he took the wafer and put it in his mouth. He then took a second host and placed it carefully in her mouth, recognizing intuitively that she had reduced use of her arms. It demonstrated Holy Communion, as Wesley called it, as a converting ordinance.

Don’t give up on the church just yet. Here were God’s people, responding from who they are to who God is. Allowing the Spirit to shape their words and actions. Discovering nothing is impossible with God. Embodying the simple prayer of devotion: “I am totally immersed in you.”