The Christian God is a queer God

I cannot begin to imagine anything queerer than the doctrine of the Trinity.

Imagine you’re back in the mid-2010s, a year or so before the post-truthers and other varieties of populist gasbags came to power in the United States and the United Kingdom and our democratic institutions came under relentless attack. Back then I was a regular on religious comment shows in the UK, wheeled in to add my own kindling to broadcasters’ attempts to fire up the culture-war issues du jour.

I’d been invited on a radio show based in Northern Ireland to talk about same-sex relationships in the church. I was in the “progressive” corner; in the other corner was a Presbyterian minister hewn pretty much out of the same rock as Ian Paisley, the hard-line Protestant leader who refused (for decades) to give ground to his Catholic counterparts, who was known for the catchphrase, “No surrender!” One might assume a battle royal would ensue. I certainly think the radio station hoped as much.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

When it was my turn to speak, I sought, as a theologian, to contextualize my views in terms of the nature of God as relational and trinitarian, of the God who invites people to dwell in one another as they dwell in God. I sensed the presenter’s growing anxiety as the conservative minister made warm and sympathetic noises in response to my very obvious orthodoxy. At one point my Presbyterian colleague interjected, in his rich Northern Irish burr, “Well, I agree with Rachel.”

Quietly, and perhaps a little smugly, I delivered my final line: “And, of course, that’s why the Christian God is a queer God.” It was at that point I lost my new Presbyterian friend.

I am left a little confused when I receive a negative reaction to the claim that God is queer. Such a claim seems so very obvious to me. I acknowledge that I have spent so long in progressive bubbles that I can underestimate just how triggering the word queer is for many Christians. I accept that, for some, there is anxiety about the permissibility of the word—it was used as a slur for gay men for so long that it has, for those over 60, generated taboo. However, I think there are other issues at play. There is a desire to protect the dignity and propriety of God and, by implication, of one’s self.

I do not know how we can save God from the queer or why one would want to. Perhaps it would be helpful at this point if I gave an account of what I mean by queer.

Nikki Sullivan reminds us that when we speak of queer in scholarly terms—as a practice and discipline—it’s used primarily as a verb: it means “to make strange, to frustrate, to counteract, to delegitimise, to camp up” those ways of thinking and being that push human beings and bodies into neat cis- and heteronormative categories and boxes. “Queering theology is the path of God’s own liberation,” writes theologian Marcella Althaus-Reid, “and as such it constitutes a critique to what Heterosexual Theology has done with God by closeting the divine.”

There’s little to fear from a queered approach to talking about God, because it’s about nothing more or less than setting God free to be God. By implication, if we are to be bearers of the image of God, called into the likeness of Christ, it’s about setting us free, too. Queer theology offers a way of unearthing what is already present—the fact that God is, by any stretch of the imagination, queer—and helping humans to inhabit that reality. It is the best kind of skewed God-talk.

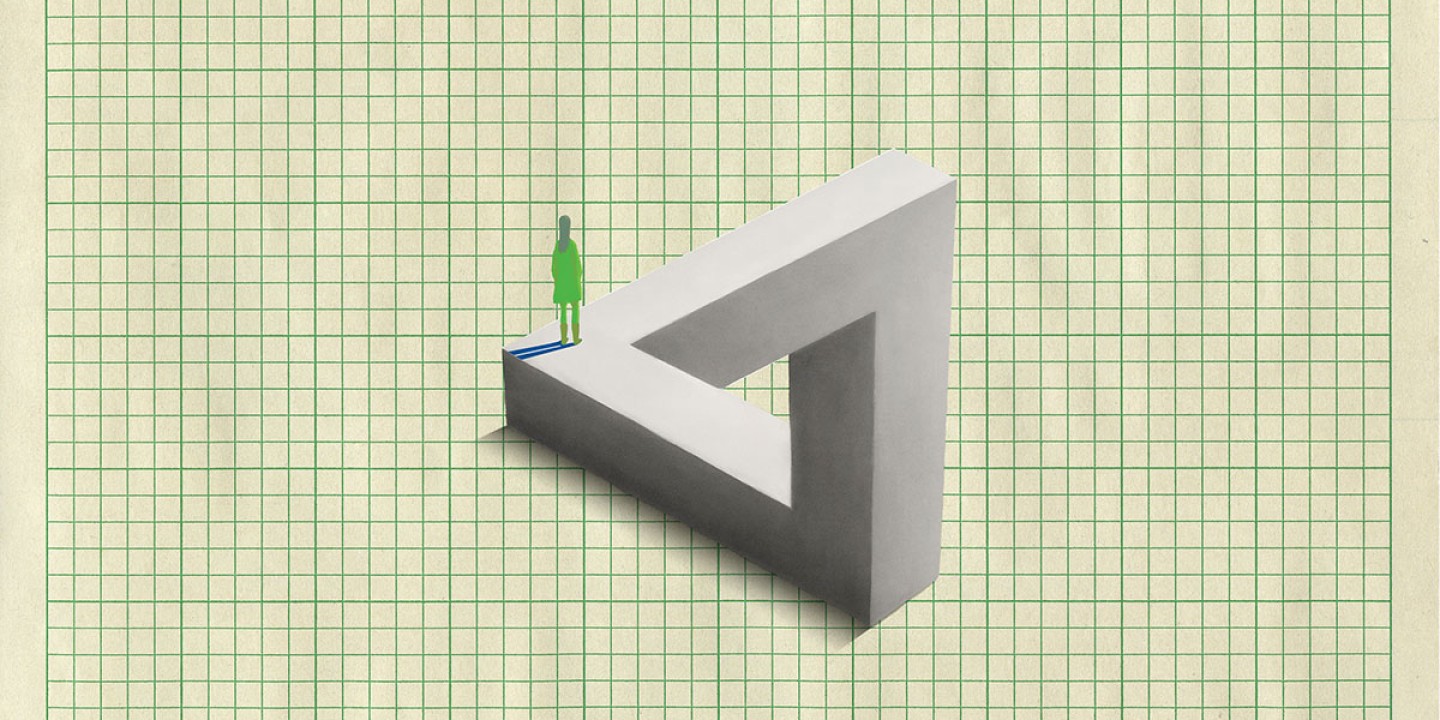

Thus, to come back to the Trinity. Whatever else one might believe or say about it, the Trinity is iconic of orthodox Christian doctrine, and I affirm and trust in this doctrine. But it is also iconic of the queerness of God. The Trinity affirms a God who is [checks notes] both essentially three and essentially one. I cannot begin to imagine anything stranger or queerer than that. It’s an outrage to simple, populist thinking. The doctrine sits there in the architecture of Christian imaginations, and we barely begin to appreciate the Escher-like queerness of it all.

Althaus-Reid talks about how so many traditional ways of talking about God “closet the divine.” The church wants to force God’s abundant and life-transforming outrageousness into hiding. As a Latinx Catholic growing up in Argentina, Althaus-Reid witnessed the garish campiness of festivals in which statues of the Blessed Virgin, the Queen of Heaven, were processed through streets. Yet for all her sense that this was something that held the possibility of queering our imaginations, she came to see that the authorized church version of the Mother of God was sanitized: Mary was presented as a rich white woman who never walked. The divine image was made bland, and the unruly facts of actual cis and trans women’s lives were erased.

One need not be a radical to hold out for a more richly nuanced and liberating version of God. A queer lens—offering a skewed and disruptive attention to what is already there and what has been excluded—reappraises our traditions and invites us to locate our weirdness and particularity in a God who receives our actual bodies with joy. Jesus has so often been sanitized. This does no honor to the biblical story of a God whose living body is pierced and penetrated and whose risen body bears the marks of trauma into heaven. Whether we identify as queer or not, a picture of God or humanity that edits out all that seems strange is not a vision of a life-giving world.