The dream and the backlash

Sixty years after the March on Washington, we don’t talk much about how nervous it made White people.

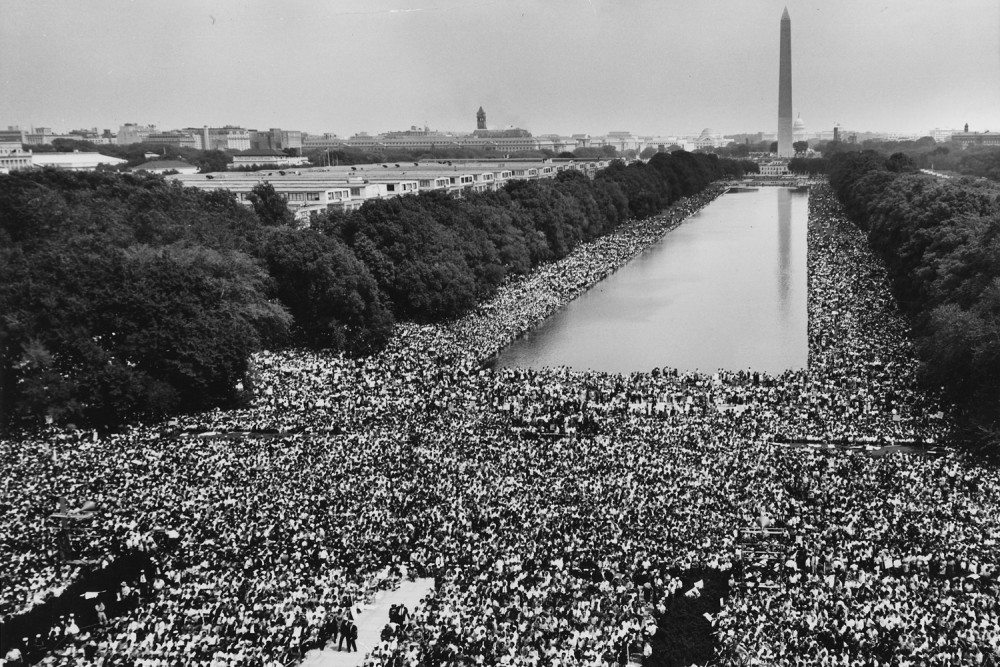

A view of the National Mall during the March on Washington, August 28, 1963 (US National Archives and Records Administration)

When 250,000 people gathered in the nation’s capital 60 years ago this month, it was the largest demonstration for human rights in US history. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is remembered mostly for the eloquent words of Martin Luther King Jr. which rippled through the crowds of people surrounding the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool. King’s spellbinding oration, full of optimism for the future, was for the ages.

To many, the day signaled fresh hope that a redistribution of social and economic power might be afoot. It was, after all, a day of social protest for jobs and freedom, not just desegregation or interracial cooperation. “We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation,” declared King. “So, we have come to cash this check.” History books cite the march as playing a role in the passage of both the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

What’s rarely discussed when recalling the throngs that assembled on the National Mall on August 28, 1963, is the nervousness of the White community at the time. Earlier that summer, President Kennedy tried to dissuade organizers from planning the march, calling their effort “ill-timed.” The unfounded idea that masses of African Americans descending on the capital would bring riots and violence along with them prompted businesses to close. Hospitals stockpiled plasma. Liquor sales and baseball games in the District of Columbia were canceled.