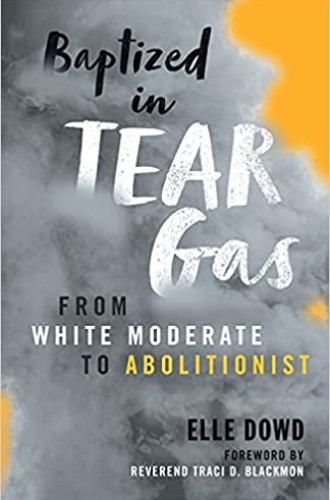

Elle Dowd’s firsthand account of the Ferguson uprising

A memoir of a White moderate’s repentance

Elle Dowd could write a lot of books. She could write about being openly bisexual and Christian. She could write about attending seminary while parenting two children and stewarding a social media ministry that inspires, encourages, teaches, and challenges thousands of followers. She could write about her revolutionary work decolonizing her denomination, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, or about her partnership with the Disrupt Worship Project.

But Dowd has chosen to write a firsthand account of the Ferguson uprising and her participation in it. She frames this participation in a classically Lutheran way: repenting of her White moderate political tendencies, she is baptized through the uprising in ways that resemble her baptism into Christ. She explains it this way:

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Baptism for Lutherans is not a singular event. It is an ongoing, lifelong journey that is complete only when our time on earth is over. I have experienced antiracism as a white person to be this way too. We are captive to the sin of white supremacy and cannot free ourselves. Racism is hundreds of years older than you or me. It is a web of lies and systems that was created for the benefit and protection of people like me, but it also acts as a suffocating trap for me and everyone else.

Baptized in Tear Gas offers a straightforward and captivating narrative. Dowd shares a portion of her life story, beginning with her politically moderate upbringing in Urbandale, Iowa, and then illustrating the choices and situations that gradually began to transform her thinking and practices.

In a sense, her real baptism into antiracism came through simple presence. She showed up after Michael Brown’s murder, and then she stayed. Just as in the sacrament of Christian baptism, Dowd writes, “we may be able to point to a single moment when we were initiated into this movement of antiracism, but it is the daily work of unlearning white supremacy, of dying to our internalized biases, that is the way to freedom.” The Ferguson uprising changed Dowd in the ways it did, she shows, because of her ongoing posture, her way of learning from and engaging with what she experienced through continuing presence.

Dowd admits early in the book she feels some tension in telling this story. She knows that centering the story of a White woman’s role in a historic uprising for Black liberation can be problematic. She approaches this risk with caution, first by acknowledging the dangers of centering herself and then by inviting White readers to make use of her book to do the work we are called to do.

In this sense, Dowd shares some of the burden Black leaders are asked to carry. Often leaders of minority liberation movements feel burdened by how much emotional labor they have to do for those who want to be allies. It’s as if they have to work for their liberation while also teaching allies how to do it. Dowd offers her book as a humble antidote, recognizing that most of the wisdom she shares was imparted to her by Black activists and scholars. She’s donating all the proceeds from the sale of the book to organizations founded by Michael Brown’s parents. Repentance, reform, reparations.

Dowd argues that coming to awareness of our indoctrination into the death cult of White supremacy is hard and holy work. Sometimes it involves getting tear-gassed and arrested, the harrowing experience of which she narrates in the central chapters of the book, illustrating along the way the fundamentally unjust and troubling patterns of policing in Ferguson.

Sometimes it comes through reading and study. Dowd notes that it never occurred to her, until she read James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree, that Jesus was profiled by police and arrested.

But most of the time the work of antiracism is undramatic, made up of ongoing relationships and small steps rather than blinding epiphanies. “It is not necessary to have some numinous experience to commit yourself to antiracism. While antiracism is radical, it is also quite ordinary in that it is most often made up of the day-to-day moments of life.”

In the end, Dowd’s message is joyful and hopeful. Although she assigns herself and all readers the difficult work, she believes there is tremendous joy in resistance. She points to data from Harvard political scientist Erica Chenoweth showing that when “3.5 percent of the population participat[es] actively in protests to create substantial, systemic change . . . change is not only likely; it is inevitable.”

Baptized in Tear Gas reads like a novella-length social media post, and I mean that as a compliment. Dowd is a social media presence. I have been changed and encouraged by following her on Facebook as much as by anyone else I connect to on that platform. Her posts unfold in a blend of honesty and challenge, offering glimpses into her anxieties and triumphs, her vulnerabilities and insights. This book extends that work, inspiring readers to join her in the harrowing and holy work of traveling along the road away from White moderation and toward abolition.