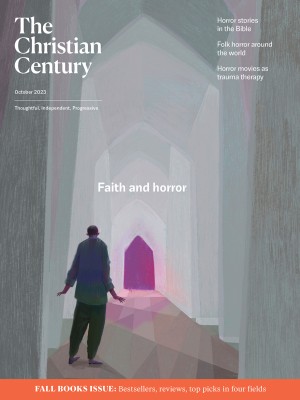

An illustration of Leviathan from the North French Hebrew Miscellany manuscript, circa 1278–1298 (Courtesy of the British Museum)

From the reputation Satan has gained over the last two millennia, you might think he was God’s original nemesis. But long before there was a Christian devil, God had a first worst enemy: the great mythical sea monster, best known by the name Leviathan.

The cosmic showdown of god versus sea monster has roots deep beneath the biblical texts. Among the colorful variety of ancient Southwest Asian traditions of gods battling sea monsters is even a Canaanite myth in which the god Baal kills the monstrous sea serpent Litan, whose name and description are echoed in the Bible.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Most of the time when the Bible mentions the sea monster, it’s getting its head bashed in. For instance, Psalm 74 offers a dramatic description of God’s defeat of the monster. Before that resolution, things aren’t looking too good for God’s people. The psalm describes how enemies have violated the sanctuary, taken axes to it, and set it on fire. The poet has one hope, that God will conquer Israel’s enemies like he vanquished his own:

You split the sea with your strength; you shattered the heads of sea monsters upon the water. You smashed down the heads of Leviathan; you gave him as food to the people, to the desert creatures. (Ps. 74:13–14, all translations mine)

This monster is so forbidding that the mere memory of God’s ancient victory over it is meant to reassure people looking at their hacked-up, burned-down sacred space.

It’s hard not to come off as forbidding when you have a lot of heads. God smashes the heads—yes, plural—of Leviathan. God is cracking skulls, and it’s not enough just to crush the multiple heads, so God also desecrates the sea monster’s corpse. God feeds its carcass to the people dwelling in the desert—apparently picking up the corpse and chucking it a few miles inland—with leftovers for the wild animals.

An oracle in Isaiah also calls up the memory of God’s ancient victory over the sea monster. Isaiah uses another name for the monster, Rahab (no relation to the biblical woman, whose name looks the same in English but is different in Hebrew):

Awake, awake, put on strength, Arm of the Lord! Awake, as in the days of old, generations of long ago! Was it not you who hacked Rahab to pieces, who pierced the sea monster? (Isa. 51:9)

While Psalm 74 has God in unarmed combat with the sea monster, crushing its many rearing heads, here God is armed. God chops up the sea monster, piercing it with some divine weapon we can only imagine.

In both of these scenes, God’s vanquishing of the sea monster is securely in the distant past. But the best monsters never stay dead, and Leviathan is God’s forever foe. Fought and slain in days already ancient to the biblical writers, the sea monster promises to resurface for another round, destined to be slain again. God’s conclusive victory is still to come. In another part of Isaiah, the prophet declares:

On that day, God with his fierce and huge and strong sword will punish Leviathan the fleeing serpent, Leviathan the twisting serpent, and he will kill the sea monster that is in the sea. (Isa. 27:1)

The irony of the forever fight is that through an assurance that God will slay the monster in a final showdown, the monster grows even larger. It won’t be killed only once—it’s like a recurring nightmare. God will always have to battle this monster. This primordial creature is the Hebrew Bible’s poster child for the dangerous looming enemy that must be defeated, so much so that Egypt and other regional enemies are sometimes referred to metaphorically as sea monsters.

It’s no wonder, then, that in the New Testament the sea monster develops from the great enemy into the Enemy. And the evolution is spectacular. The sea monster becomes a “giant red dragon” with seven heads, “the ancient serpent who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world” (Rev. 12:3, 9; 20:2). Where the Hebrew Bible refers to the sea monster, or even to Leviathan by name, the Septuagint (the Greek version used by New Testament writers) uses the word dragon. The descriptions in Revelation of the devil as a giant ancient “dragon” and “serpent” are lifted from Isaiah, where Leviathan is both serpent and sea monster—or, in the Septuagint, “serpent” and “dragon” (Isa. 27:1). The sea monster has become the very picture of the devil. You know you’re bad to the bone when you make a good template for the Prince of Darkness.

Slaying, smashing, crushing, piercing. From the first clash to the final epic battle, everything would lead us to expect consistent animosity between God and this enemy. But God’s proclivities are never quite what we expect. As it turns out, God also delights in his sea monster.

In Psalm 104, Leviathan is praised as a thing of wonder. The psalm marvels at creation: God stretched out the heavens like a tent, set the earth on its foundations, covered it with the ancient deep like a garment, and made the streams flow. There are branches for birds and grass for cattle. God made moon and sun, darkness and light; wild animals prowl at night, and people work all day until the evening comes.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because the first 23 verses of the psalm name almost every facet of creation from Genesis 1. But in Genesis, the pinnacle of creation is humankind. The poet of Psalm 104 takes a very different view of the culmination of God’s creation:

Lord, how many are your works! In wisdom you have made them all; the earth is full of your creatures. There is the sea, great and wide; creeping things without number are there, living creatures small and great. There ships go, and Leviathan, whom you formed in order to play with him. (Ps. 104:24–26)

Here the pinnacle of creation is Leviathan. In Genesis, God finishes with humankind, having finally created something “in his image” (Gen. 1:26–27). In this psalm, God finishes with Leviathan—having finally created his companion. And there’s more: he’s God’s pet! In one Talmudic reading of this verse, God plays with Leviathan for three hours a day.

The poet continues, directly following up the praise of Leviathan among all God’s creatures:

All of them look to you to give them their food in due season. You give to them and they gather it up; you open your hand and they are satisfied with good things. (Ps. 104:27–28)

How recently we saw God slaughtering Leviathan, crushing the multiple heads of the ancient monster and feeding his carcass to the people of the desert! And yet, here is God now, playing with Leviathan and feeding the monster out of his open hand.

A trusting pet looks to God for food and care. Also: heads are smacked down onto the surface of the water, a creature is pierced, a monstrous serpent twists and speeds through the deep. We’ve seen the sea monster from two very different angles; yet, we’ve hardly caught a glimpse of the monster’s body.

There is one place in the Bible where an extended, graphic description of Leviathan appears. It happens in the book of Job. After losing his livelihood, watching his children die, and being tortured with physical agony, Job repeatedly cries out to God. Near the end of the book, God finally responds to the bereaved, tormented subject of his experiment—but only to say, “Gird up your loins like a man!” (Job 38:3).

With those opening words, God delivers a long litany of rhetorical questions that run through the whole of creation, a lot like Psalm 104. “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?” (Job 38:4). “Have you seen the storehouses of hail that I’ve saved for a time of trouble?” (38:22–23). After cataloging the waters, the stars, and so on, God moves on to the animal kingdom. After the mountain goats and the ostriches, just as we’re expecting to find human beings as the crown of creation, we instead meet something very different.

In the praise of creation in Psalm 104, Leviathan found his place of pride after humankind. God’s speech in Job one-ups this, leaving out human beings altogether. As his long, glorious finale, God describes Leviathan:

Can you pull out Leviathan with a fishhook? . . . Can you put a rope in his nose? . . . Will he speak soft words to you? Will he make a covenant with you? Will you take him as a servant forever? Will you play with him like a bird? . . . Will you spear him, harpoon him, and let the traders haggle over him? (Job 41:1–7)

The contrast with God’s earlier rhetorical questions about the earth is jarring. Those questions pointed to God’s control over creation: he determined the earth’s measurements, made the boundaries of the sea (Job 38:5, 8). Now God’s questions emphasize how Leviathan is beyond all control.

Some interpreters suggest that these questions point to things that Job can’t do but God can, an idea with a high theological-comfort quotient. It has additional appeal as well, since the image of God playing with Leviathan “like a bird” would tie in nicely with Psalm 104, where God created Leviathan in order to play with him.

But swirled together within this series of questions, God also asks whether Leviathan speaks softly to Job and makes a covenant with him. If God’s rhetorical questions suggest that he could harness Leviathan, then they also suggest that Leviathan speaks tenderly to God and that the two have a covenant.

Neither option is particularly comforting. Either God created a monster beyond his control and let him loose, or he plays with Leviathan while the sea monster whispers sweet nothings in his ear.

God has some last words of advice before coming to the climax of his speech. First, he warns of Leviathan’s power. Lay a hand on him once, God says, and you’ll never try it again; no one’s so fierce that he should try to rouse the monster (Job 41:8, 10). Then God veers off into threats and warnings about his own power, like a man puffing up his chest as he heatedly steps in to defend his beloved: “Who then will stand before me? Who will confront me, and I’ll repay him? Under the whole of heaven, who?” (41:10–11). Try me, says God. Come at me!

With this, God turns to an awe-filled description of Leviathan:

I will not keep silent concerning his limbs, his mighty power, and his incomparable form; who can strip off his outer garment, who can penetrate his double coat of armor? Who can open the doors of his face, his teeth of terror all around? His back is rows of shields closed up with a tight seal, coming one after another so that not a breath can come between them. One is fused to the next; they clasp each other and cannot be separated. (41:12–17)

These details are alarming. Leviathan’s giant jaws open wide to reveal terrifying teeth all around. (The Hebrew literally means “encircling.”) Those jaws are “the doors of his face”—not just the doors of the mouth, as in other poetry (e.g., Micah 7:5), but giant doors that open up the whole face. His enormous jaws are heavy and powerful, impossible to pry open. His scales are like impenetrable fused shields, and that’s just one of the two layers.

Leviathan seems more crocodilian than serpentine, but with utterly unnatural features that take him far outside the scope of any living creature. His fantastic monstrosity becomes more glaring as God continues:

His sneezes flash forth light; his eyes are like the eyelids of the dawn. Out of his mouth go flaming torches; sparks of fire escape! Out of his nostrils comes smoke, like a basket with bulrushes ablaze. His breath could kindle coals; flame comes out of his mouth. In his neck lodges strength; terror dances before him. The folds of his flesh cleave together, hard-cast and immovable. His chest is hard as a rock, hard as the bottom grinding stone. When he rises up, gods fear! At the crashing, they are beside themselves. (Job 41:18–25)

Leviathan breathes fire. It’s like a blowtorch from his fang-ringed mouth and smoke from his nose. His eyes glow red like the first glimmer of dawn. And he has a neck of brute strength. Even the folds of his flesh—literally “the drooping parts”—are hard-cast, in Hebrew a word used to describe metal. His chest is like the hardest stone, the one that’s used to grind other things to smithereens.

This section of the poem ends with a vivid image of the sea monster rising up and hitting the water again with a thundering splash. Remember the good old days when the image of Leviathan hitting the water was invoked in celebration of his defeat, like the scene of a cosmic action flick where God finally vanquishes the monster? “You shattered the heads of sea monsters upon the water; you smacked down the heads of Leviathan!” (Ps. 74:13–14). This time is different. Leviathan lifts himself out of the water—and gods fear! At his crashing back down, even the gods panic.

Here God pauses for an interlude about how no weapon forged against Leviathan can stand: even if a spear were to reach him, it would break. Iron and bronze are like straw and rotten wood to him, cudgels and slingstones like windblown chaff (Job 41:26–29). Then God has one more part of Leviathan to describe:

His underparts are like the sharpest of potsherds; he crawls like a threshing sledge in the mud. He makes the deep boil like a cauldron; he makes the sea like a pot of ointment. Behind him, he leaves a shining wake; one would think the deep to be white-haired. He has no equal upon the earth, a created thing without fear. He looks upon everything lofty, he is king over all the proud. (41:30–34)

Leviathan’s belly is so jagged and sharp that he cuts into the ground as he crawls. That’s right, the ground. This sea monster can come out of the ocean straight toward you, like that girl in The Ring crawling out of the TV. He crawls up onto the land, scraping as he goes.

If there is any lingering question about how monstrous Leviathan is, here’s another clue: he boils the deep as he swims through it. His body also leaves the sea “like a pot of ointment,” whatever that means—maybe he oozes slime. He shoots through the water, leaving a shining wake.

Leviathan has no equal, God concludes: he is the only created thing with no fear. He is unparalleled, reigning over all. In all of God’s speeches in the Bible, nothing compares to this 23-verse description of Leviathan’s incredible body, part by part.

In the biblical speeches of humans, though, something compares. It’s in Song of Songs. The lover describes his beloved’s form in intimate detail, savoring each part, poetically exploring her whole body with amazement:

How beautiful you are, my darling, how beautiful! Your eyes are doves behind your veil. Your hair is like a flock of goats moving down Mount Gilead. Your teeth are like a flock of shorn ewes that have come up from the washing. (Song 4:1–2)

He continues, describing her lips and mouth, then her temples and her neck, and then her breasts. The young woman in turn describes her beloved, first his skin, then his head and hair, his eyes, cheeks, and lips, and then continuing downward: “His arms are rods of gold, set with topaz. His belly is a panel of ivory, inlaid with lapis lazuli. His thighs are alabaster pillars, set upon foundations of gold” (5:14–15).

To most readers of the Bible, this form of poetry may seem unique to the Song of Songs. But it isn’t. This slow gaze down the loved one’s body, pausing to praise each place the eye falls, is a well-known genre of poetry called a wasf (Arabic for “description”). A snippet of an ancient Egyptian wasf reads: “Long of neck, white of breast, / her hair true lapis lazuli. / Her arms surpass gold, / her fingers are like lotuses.”

This poetic form would have been familiar to ancient readers. Think about how we recognize the tone of a limerick by its familiar contours: when we hear, “There once was a girl from Nantucket,” we know generally what sort of poetry we’re dealing with. We know the genre, and we know to expect something lighthearted and likely (ahem) discourteous. In a similar way, an ancient reader or listener would recognize the tone of a wasf and understand the sentiments it conveys.

When God describes Leviathan’s body to Job as if gazing slowly over each part, this is not a biology lesson. It’s a wasf. That doesn’t mean it’s sexual, like in the come-hither Song of Songs—but it is positively an expression of intimate knowledge and passionate love. God’s poem is an expression of love, and he lingers over every detail.

Contrast this with how God relates to Job. The first part of God’s speech is already dismissive, jettisoning humankind from the survey of creation. Then the Leviathan wasf twists the knife. Job has cried out, pleading for God to respond, devastated at God’s utter silence. When God finally answers, he says that his heart belongs to another. Leaving the poet of Psalm 104 in the dust, Job’s God swaps out any description of humankind for a classic descriptive love poem about the infamous sea monster. In that relationship, and in his own effusive words, God’s allegiance comes into painfully sharp focus. We finally know where we stand.

To be fair, Leviathan is a better match for God. People can be so . . . moral. God identifies with the monstrous. Leviathan can never be tamed, and neither can God.

This article is adapted from God’s Monsters: Vengeful Spirits, Deadly Angels, Hybrid Creatures, and Divine Hitmen of the Bible, forthcoming in October from Broadleaf Books.