Making room in the UMC for the Spirit’s work

The denomination’s new regionalization plan is a marked break from its colonial hangover.

As we were leaving the convention center in Charlotte after a long day of legislative meetings, a friend and prominent leader within our denomination whispered to me something he didn’t want overheard: “Being a global church is really hard work.” His simple yet insightful observation is another way of saying what my colleague Barry Bryant often maintains: Methodism’s biggest challenge is living a contextual theology in a connectional polity.

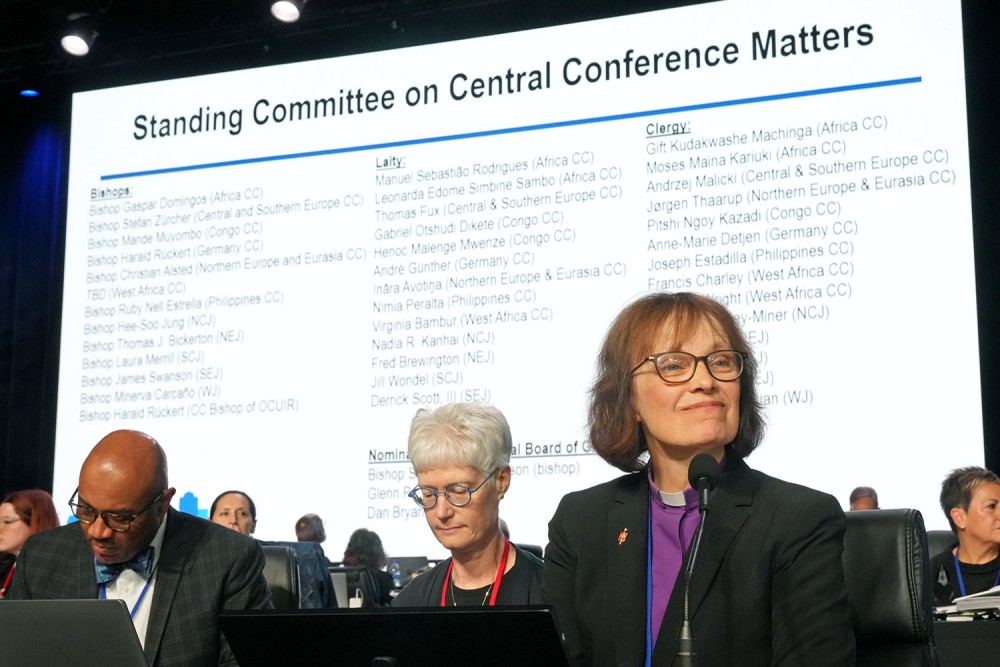

At this year’s United Methodist general conference—a quadrennial global gathering of delegates representing ecclesial regions throughout the world—the church was striving to express in doctrine and polity its most faithful understanding of who God is calling the Methodist people to be. For generations we have been consumed by debates over biblical authority, human sexuality, regional differences, colonial legacies, the accompanying attempts at decolonizing our polity and theology, and the demographic shifts that have altered the locus of power in the church’s decision-making apparatus.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Put simply, the church’s regions outside the United States now have a greater influence and vitality than those within the US, yet much of the financial and organizational power structure remains firmly ensconced in the US. For much of the last 50 years, traditionalists within the US have been theologically aligned with those outside the US, but those non-US regions have remained financially reliant on the more theologically progressive churchwide leadership. With the sizable exodus of traditionalists from the United Methodist Church over the last five years, the theological and political dynamics shifted considerably, setting up a dramatic and consequential assembly.

Hope and fear were palpable as the delegates and others gathered in Charlotte. Years of political machinations, countless negotiated agreements and declarations, and battles over misinformation and disaffiliation would now, at last, either be settled or send the church into further disarray. I remember well how confidently many progressives entered the 2019 special general conference, assured they had garnered the support of sufficient delegates from outside the US to quell the traditionalists’ attempt to harden the church’s stance on human sexuality in the denomination’s governing tome, the Book of Discipline. Instead, many left in tears, aghast that restrictions were tightened rather than loosened. The scars of 2019 are still raw on all sides of a debate that has consumed denominational life for longer than I have been alive. Would this gathering in Charlotte bring reprieve or inflict greater harm and chaos?

The 2019 general conference was a watershed event for many United Methodists. I remember sitting in the observer section of the St. Louis arena where the assembly took place and typing a letter to my bishop surrendering my ordination, tears streaming down my face as I did so. I was no longer able to justify being part of a denomination that excluded from leadership the LGBTQ people in whom I had so clearly witnessed the gifts and graces of God at work. I could no longer justify representing a church that would not recognize the unions I had blessed and marriages I had officiated between people whose love of each other and of God was so palpable, faithful, and beautiful.

Weeks later, my bishop convinced me to stay in the fight, to be a part of helping this church grow into the kind of global Christian community that lives its espoused values and truly welcomes all into its ranks and leadership. It wasn’t an easy decision, but I’m glad that his wise counsel persuaded me, because in the years since, I’ve come to learn more about what it means to live a contextual theology in a connectional polity—and about how important it is not to walk away when hope seems lost.

I’ve long disdained the argument that United Methodism has been slow to follow the path of our liberal Protestant siblings because of the power and influence of our African and Asian members. That is far too simplistic an argument, and it positions people of color as the ones restraining an otherwise open and affirming church from embracing all people—while acquitting the predominantly White US regions of the church of ongoing harm. Those who repeated that argument incessantly failed to take seriously the theological and doctrinal concerns these communities raised, and they likewise failed to take seriously the complexities of living in a connectional polity.

This is part of the complication presented by the regionalism plans approved by this general conference. Critics argue that allowing different approaches for different regions is simply a way for US Methodists, freed from the influence of the church’s more traditionalist members, to move forward with liberalizing reforms without being beholden to the remaining presence and theological perspectives of its central conferences (as regions outside the US are called). It is the height of colonialism and hypocrisy, critics argue, because it demonstrates that the US regions of the church refuse to live in a polity in which Black and Brown people outside the US carry such significant power and influence. Further, it conceals the fact that other churches have experienced precipitous decline in the aftermath of liberalizing reforms, and for the UMC to do so will potentially impact the church globally in similar ways. They’re not entirely wrong.

Yet this critique obfuscates an important biblical, theological, and ecclesiological perspective. The Christianity that American missionaries often carried to these presumedly unenlightened and inferior peoples was treated as a force that would supplant local customs and westernize heathen cultures—instead of proclaiming a message of love that could be woven into communal life. It prioritized Western concerns and practices and often belittled Indigenous ways of knowing and being. In retrospect, that highwater mark for a particular kind of formalized faith always carried the seeds for its own destruction. It was the apotheosis of the forces dragging Christianity away from the early Jesus movement’s wildness by attempting to erect rigid structure around the Spirit, who does not like to be caged.

This has always been true; it is evident from the church’s inception to the present. When we look back to the early Christianity depicted in Acts and Paul’s letters, we see a wide variety of communal priorities. The church in Corinth, for example, is focused on navigating eating practices among its members, while the church in Rome is busy reconciling the community’s theological conflict. Paul, in turn, offers particular advice for each—rather than trying to make the Romans adopt the Corinthians’ focus. While there is an implicit authority in Paul’s letters, that authority is derived from relationship and was affirmed from within the community. In contrast, the 20th century model of churches with shared worship style, common theological priorities, and tightly yoked structure fashions the scaffolding for faith into an idol.

The new regionalization plan is a marked break from that colonial hangover. Individual churches will now have authority to tailor their priorities and practices to what nurtures their people. While this would be proper solely out of a commitment to decolonization, it’s also a reflection of shifting demographics within the UMC. Two-thirds of United Methodists now live in Africa or Asia, a proportion that is projected to grow in coming years. It is essential for the church to empower local conferences, trusting them to know what their people need most and resourcing them to provide it.

I’ve seen firsthand how this approach bears fruit. Like many US seminaries, for years Garrett-Evangelical, where I serve as president, has seen more and more M.Div. students matriculate from Africa and Asia. Whenever we see rising numbers of students from a particular place, we send international students, faculty, and administrators there to determine how we can partner with institutions in their home countries. In the past three years, delegations have traveled to India, Korea, Brazil, Chile, and Zimbabwe—not to figure out how we can extract more tuition dollars but to follow the movement of the Spirit, to learn how we can partner with local churches and co-create a new model of global theological education. The result has been one of the most dynamic periods of educational innovation I have witnessed. We’re developing plans for faculty and student exchanges, reconsidering curricular assumptions, and creating hybrid models in which students enroll in coursework on multiple continents and learn together. We’re about to launch a fellowship cohort in partnership with Africa University to strengthen leadership on and for the continent. We’re co-creating similar experiments in Latin America, Asia, and different regions of the US.

All of this has been made possible by meeting people where they are and asking simple questions: How can we together breathe life and energy into the ministries you’re already doing? How do we best discern God’s Spirit and our calling in what we co-create? What is needed to expand that work and the people it serves and includes? How can both contexts be strengthened and transformed by this partnership? I can’t convey how hopeful it makes me to see the UMC now embracing what so many of its constituent institutions and churches are already doing. Regionalization is not a recipe for “do as you please theology,” as critics are wont to say; rather, it is an attempt to recover a biblical approach that assumes God speaks and moves in ways that people understand—and that honors their wisdom, experience, and concerns.

As the structures of the church adapt—granting greater authority to individual regions to shape their ministry and empowering deacons by granting them sacramental authority in the ministry settings where they serve—it is essential that we also commit to expressions of faithful and consistent doctrine. While regionalization will permit conferences to tailor form and priorities to their respective cultures, this cannot be an excuse to jettison shared theological principles. The general conference’s decision to lift the ban on LGBTQ ordinations and weddings exemplifies how we can live into faithful obedience to the gospel while also honoring the theological diversity within the UMC.

Something traditionalists fail to acknowledge about those who embrace and celebrate full inclusion in the church is that theological integrity and rootedness are central to our ecclesiology. We aren’t simply driven by secularist agendas and ideologies; rather, our theological worldview is shaped by our reading of scripture and understanding of tradition. Scripture reveals time and again that God, ancient communities, Jesus, and the early church changed their minds and adapted practices, letting go of previously held perspectives. Earlier this year, the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria ordained its first female deacon, in contrast to its previously held doctrine. Thinking and believing differently does not mean we jettison the church’s historic faith or eschew biblical authority. It means we take God’s immanence seriously enough to believe God is still guiding our unfolding work and ministry.

The Spirit is at work in more expansive ways than we can fully comprehend, and this is consistent with the diversity of thought and practice that has characterized the Christian church since the time of Jesus’ ministry. There is unity, even theological unity, in that diversity. The church’s early councils were global gatherings meant to settle disputes. Once the majority settled those disputes on terms amenable to them, those in the minority did not all miraculously change their faith and practice. While some certainly did, most instead embraced an alternative orthodoxy (as the Franciscans later coined their theological method) that thrived and continues to thrive to this day, living in dynamic tension and dialogue with the rest of the tradition. Such dynamic tension and dialogue is a strength of the church. It’s not something that we should seek to eradicate.

The ban against full LGBTQ inclusion in the UMC violated fundamental biblical principles. It transformed misreadings of a handful of texts into a cudgel, harming LGBTQ folks and their allies. It obscured the gospel’s clear and repeated foundations: all people are created in God’s image, God is fully revealed in Christ for all and to all, God’s love extends radical welcome to everyone, and any attempt to create hierarchy that separates people from God’s grace, mercy, and welcome is sinful. The tears wept on the general conference floor—as delegates voted overwhelmingly to extend God’s justice where it had been withheld—testify to the power of righteous action.

That vote is just the beginning of a longer process, however, in which churches and members who disagree walk alongside each other. This ruling does not and should not dismiss the conscience of people who still grapple with it; it simply means those people cannot be gatekeepers who shut out others from being ordained or married in the church. The general conference, in deciding to authorize same-sex marriage, also ensured that those who disagree cannot be compelled to exercise their ordination contrary to their conscience.

Earlier, I mentioned that my seminary has embarked on fruitful collaboration with international partners. These partnerships are not without the same kinds of tension that manifest in discussions over LGBTQ inclusion. Sometimes our theological values conflict with those of our colleagues, and sometimes their values move them to push back against our own. Nothing is gained, however, by pretending that these differences don’t exist—or by trying to use historic colonial power to force people to adopt our perspective. We are called to do the far more difficult work of laboring in community to pursue a consensus that can lead us forward in the Spirit’s power and wisdom. The Pauline letters reveal that this has been messy work since the church’s inception. But it’s the only way that we can heal from imperial wounds and pursue collective thriving.

Ultimately, the future of United Methodist Christianity will not be determined inside institutional structures. That’s an odd sentence to write as a seminary president and as someone who has dedicated much of my life to strengthening the church’s institutions. Yet I’ve never been more hopeful about where the UMC is headed, nor more certain that God is calling us to a more decentralized structure in which the Holy Spirit has room to move freely. The general conference’s four landmark decisions—regionalization, moving toward full communion with the Episcopal Church, granting sacramental authority for deacons, and lifting the ban on LGBTQ weddings and ordinations—reveal our unmistakable bearing toward nimble Christian communities that let God’s justice flow into whatever shape most faithfully serves their people in their respective contexts.

The entirety of United Methodism is about to discover what my seminary now knows: building reciprocal networks of churches, welcoming the full diversity of God’s people, and proclaiming the gospel boldly will be where our resurrection lies. Being a global church is really hard work, but it is also the greatest gift God has given the people called Methodist.