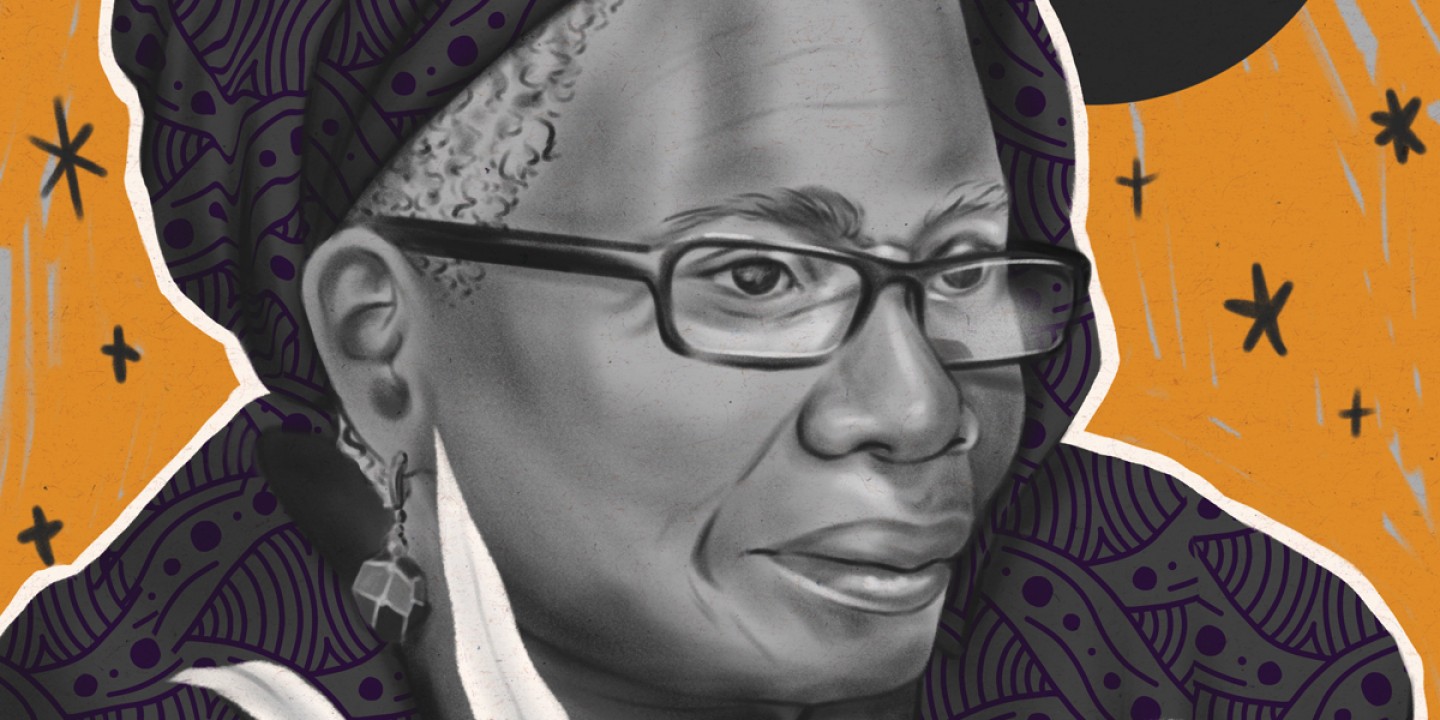

Mercy Amba Oduyoye and her Circle

The Ghanaian theologian has long insisted that the experiences of African women are the experiences of the church.

Theologian Mercy Amba Oduyoye tells a story of how when she was a girl attending Mmofraturo, a Methodist girls’ boarding school in Kumasi, Ghana, she and her classmates felt empowered to make scripture their own, so they took interpretive liberty. Since the biblical proverbs were so close to the proverbs of their Akan culture, the girls would recite Akan proverbs in place of the proverbs of the Hebrew Bible. They confidently lived into their hybrid religious identity. For these girls, the sentiment behind the biblical proverbs already lived deeply in Akan culture. Why not translate their own cultural wisdom into biblical language?

Not only did Oduyoye and her classmates hear themselves in the lessons of scripture, they counted themselves equal members of the church. This was quite remarkable, for the girls had been raised in a culture that honors women for their genealogical role in society but expects men to be the dominant decision-makers—and in a faith tradition that places women at the bottom of the theological hierarchy. The confident communal witness of those girls stayed with Oduyoye as she grew up, giving shape to her theological imagination and her passion for ecumenism.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Born to a self-assured woman and a preaching father, Oduyoye has dedicated her life to interrogating the complexity of theological concepts, language, and practice—with both African and Western cultural nuances in view. She consistently raises her voice to insist on men and women’s equality in a culture that endorses values of communal care and wholeness but fails to demonstrate them toward its own women. At the same time, her theological voice asserts the full value of all people in the church. Christian practice, Oduyoye believes, is unstable unless it includes the perspectives of all of the church’s members. This is because all members of creation are entangled with one another in God, who is the center of life.

God lived among humanity enfleshed, and women—from the prophetess Anna to Mary Magdalene—were the first to recognize this. African women are drawn to Jesus because of the way he sought to draw all of creation back to God’s self, Oduyoye asserts. He knew imperial resistance, subverted gendered ideologies, and elevated those typically overlooked in their communities and societies. To African women, Jesus sounds more like an African woman than anything else.

The question of right relationships is critical to Oduyoye’s theological stance. Because humanity is God’s creation, human beings’ relationships to one another must be determined by their relationship with God. African women’s theological anthropology affirms God’s declaration that all creation is good. It allows African women the opportunity to echo their worth through their Creator’s words and reject any ideology that says otherwise. It is this mentality that sustains the Christian church.

For African women, Oduyoye believes, the Christian church is an instantiation of God’s movement on earth. Its power is not in its ability to dominate but rather in its ability to reflect God’s care for creation. The gift of the church is its multiplicity: it is diverse in nature, and God affirms it as such. In particular, Oduyoye emphasizes that African women and the church are not separate entities; the experiences of African women are the experiences of the Christian church. The flesh of the church is dense with the stories of African women just as much as with those of any other people group.

Thus, according to Oduyoye, the calls for justice, participation, and ministry that African women claim for themselves are not merely vested points of interest; they are the crux of a holistic Christian ecclesial life. These called-forth truths are the full revelation of the church. If the church does not embody these realities for itself, it fails to be itself. Similarly, any theological platform that rations God’s love and power to a select few conveys not Christian theology but a distortion of it.

Oduyoye was raised in a religiously pluralistic society, and she describes herself as the practical type, interested in what the church is doing in the world. Thus, a passion for ecumenism came naturally to her, and she has worked for decades to fill in the gaps for underrepresented voices in ecumenical circles. She has served as a founder or founding member of numerous groups, including the World Council of Churches Ecumenical Decade of Churches in Solidarity with Women, the Ecumenical Association of Third World Theologians, and the Institute of African Women in Religion and Culture at Trinity Theological Seminary in Legon, Ghana.

Perhaps most importantly, Oduyoye formed a space for African women thinking theologically—a sacred and much-needed circle that allows African women of various ethnicities and faiths to theologize together about how the Divine moves in and through their lives. African women academics knew that their communities’ cultural and religious emphases could be used for good, that they simply had to be mined for their constructive features. But these women lacked a formal setting for tackling such questions and having these conversations together. Oduyoye saw how they needed a place where they could communally interrogate the role culture and religion play in women’s lives. In the 1970s, she began to dream up a place, a gathering, where women with similar experiences could learn from one another, build each other up, and create new conditions for African women’s wellness.

In 1989, with the help of an international planning committee, Oduyoye cofounded the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians. Today the Circle, as it has come to be affectionately called, is one of the largest African women’s communities focused on religious conversation, study, and publication. Its existence shows that African women—who, as Kenyan theologian Teresia Mbari Hinga puts it, “had been discussed, analyzed, and spoken about and on behalf of by men and outsiders as if they were not subjects capable of self-naming and analysis of their own experiences”—have their own contributions to make to the discourse about the shortcomings of culture and religion. These women link together and, through communal and scholastic sharing, work to heal themselves from the abusive use of culture and religion against them. In their joining together, they have committed to heal not only themselves but also the communities around them.

The Circle destabilizes masculinity as the center of theological witness, highlighting instead the contributions of women—both Christians and those of other faith traditions who convey a theological focus as they live out their faith in the modern world. Its main concern is women’s wellness and liberation; therefore, all African women who do theological work against systems of oppression are welcome to join its networking and scholastic mission. Membership is not pressure filled: to be a member of the Circle, all one needs to do is produce some writing. More valuable than any membership fee, writing ensures the growing visibility of African women’s theology.

Void of official headquarters or strict operational structure, the Circle sustains itself through shared ideas and responsibility. Refusing a hierarchical structure allows women to rotate leadership on a case-by-case basis as they are moved to see an idea to completion. With regional chapters (or zones) all over West, East, Central, and South Africa as well as in the wider diaspora, the Circle functions as a series of networks within a network. These chapters gather as a whole every five years (originally every seven years), inspiring transformed ways of thinking about biblical hermeneutics, theological frameworks, and church and society at large. Through their emphasis on practicality and communal theology, members address numerous overlapping and sometimes evolving issues, many of which involve women’s spiritual, economic, and physical health.

The Circle’s inaugural meeting in Accra, Ghana, in 1989 was attended by 80 women scholars from all over the African continent and 200 churchwomen from Ghana. They met under the theme and heading “Daughter of Africa, Arise!” The biblical mandate “Talitha Cum!” (Mark 5:41) captures the Circle’s origin, purpose, and necessity: to affirm that girls and women are not dead in their communities but very much living beings in Christ.

Most of the Circle’s members can easily relate to the two female characters in Mark 5. As Botswanan feminist theologian Musa Dube writes, some of them are “the bleeding woman who reaches for power.” They call out to the generations after them, providing hope that healing is possible; they “are the ones calling out ‘Talitha Cum!’ to the unfinished business of a young girl’s life.” In the Circle, the old and young are interconnected, for if one gains name and life, it is so that the other may be privy to the same. African women look out for each other’s wellness. They tell stories about their survival and successes.

By providing intergenerational networking and support, the Circle has grown in number and influence. At its second meeting, held in Kenya in 1996, Kenyan religion scholar Nyambura J. Njoroge reports that there were nearly twice as many scholarly registrants as at the first meeting. One hundred and forty women from various areas (including West Africa, francophone Africa, and Southern and Eastern Africa) gathered to present, listen to, and workshop papers. Eventually many of these papers were published—a gift for many of the women, since their publishing opportunities were scarce.

There is something to be said for women creating and inhabiting new spaces in order to feel seen and to understand that they usher in their own liberation. The Circle’s history and continuing legacy prove that African women’s writing in theology—Christian theology especially—can have a significant impact. Collaboration is a critical part of the Circle’s growth as it continues to offer women of African descent space to be supported, to support one another, and to network.

Oduyoye, who will turn 90 later this year, has contributed to Christian theology in African and global contexts for over six decades. She has created a movement of African women’s theological vocality that is critical to the continual growth of the Christian theological canon. In both the formation of African women’s theology and the creation of the Circle to affirm and cultivate such theological work, she has helped African women not only pull a chair up to the table but fashion their own chairs.

African women’s theology is reflective work. It holds a mirror up to the Christian church and to the African continent and reflects back both what they need to do and how they need to change in order to live into their true identities—identities enriched by flourishing together.

As long as the need exists to uplift women into proper life and human dignity, African women’s theological work is never done. In the Circle and beyond it, in the next generation and outside the continent, groundbreaking possibilities and generative sites exist for African women’s continued theological presence. Their voices and work will create stronger foundations for life not only in Africa but all over the world.

This article is adapted from her book The Theology of Mercy Amba Oduyoye: Ecumenism, Feminism, and Communal Practice, published this month by the University of Notre Dame Press. Used with permission.