Monsters and their beautiful work

Claire Dederer thinks through what it means to consume art produced by people who have said or done terrible things.

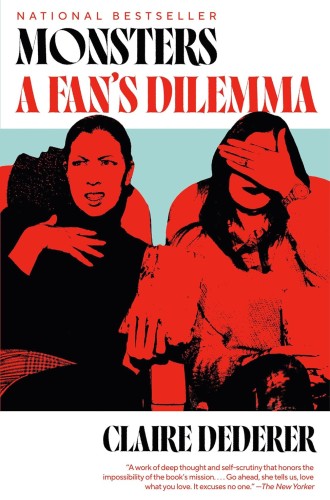

Monsters

A Fan’s Dilemma

A spin instructor once told me that she never pays for the Kanye West songs she plays in class. The music is good but the artist is ethically questionable, so she refuses to put money behind it. When she wants to play anything by Kanye, she illegally downloads it.

I picked up Claire Dederer’s new book wanting an easy answer to how to deal with Taylor Swift’s enormous carbon emissions, the accusations against Lizzo for fostering a harmful work environment, John Mayer’s pattern of dating women half his age, and Kanye—whose antisemitic and Nazi-sympathizing remarks have made me question if I can listen to even his earliest music. Monsters is Dederer’s attempt to think through what it means to consume art produced by people who have said or done terrible things, from J. K. Rowling to Woody Allen to Roman Polanski to Ernest Hemingway. The word monster shows how we mark these artists as something other than ourselves: “Monster implies—insists—that the person in question is so terrible that we could never be like them.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Although she begins by asking whether artists can be separated from their biographies, Dederer comes to realize that her project is actually an autobiography of a representative person who consumes art. How do audiences decide what to love and what to hate? Can we “love the art but hate the artist?”

Dederer settles on a central metaphor for the art created by monstrous artists. If a work of art and the biography of its producer cannot be fully separated, as she comes to believe, then the biography acts as a stain on the art. Picture a beautiful quilt crafted by hand and given to you by a loved one. You cherish this quilt more than anything: it has comforted you through the years and carries many memories. Now, imagine that you spill a fresh glass of cabernet all over the center of the quilt, and there is no way to get the stain out. Do you toss the quilt? “The stain—spreading, creeping, wine-dark, inevitable—is biography’s aftermath. The person does the crime and it’s the work that gets stained. It’s what we, the audience, are left to contend with.” While for some people “that stain ruins the whole work, for others it is just something you have to face up to.”

As she proceeds, Dederer begins to question her own feminism. To point a finger at a monstrous artist and repudiate their art, she notes, is a liberal tendency (in the sense of traditional liberal political philosophy). But simply denouncing the art and walking away, as her liberal feminism would have her do, does not deal with the core issue of material power or make space for an artist’s biography to change the way we interact with the art. Cancel culture, Dederer suggests, is the current manifestation of this liberal desire to point fingers and denounce: “If you look hard enough at anyone, you can probably find at least a little stain. Everyone who has a biography—that is, everyone alive—is either canceled or about to be canceled.”

So, why does it hurt so badly when we discover that an artist we love may not be a beacon of goodness in the world? Why do I feel personally afflicted when Taylor is called out for her massive carbon emissions? The answer lies in parasocial relationships, the one-sided bonds we form with people, and especially celebrities, online. I am hurt because I think I know Taylor Swift. Her art has carried me through adolescence to adulthood, and it is painful to face up to the fact that the person I have created in my head, to whom I attach so much joy, is not actually real. It’s hard to admit that I am attached to a reproducible image of Taylor, not Taylor herself.

But reproducible images are all we have. “Aesthetic experience is tied to nostalgia and memory—that is to say, to subjective experience,” explains Dederer. Thus, “nostalgia, personal experience—these things become meaningful in terms of calculating the badness of the act against the greatness of the work.” If the goodness of the meaning I attach to Taylor’s songs outweighs the badness of her carbon emissions, it seems, then I can keep listening to her music—at least for now.

But where do I draw that line? I may decide that the stain left by Taylor’s carbon emissions is small enough to overlook while the stain left by Kanye’s antisemitism is a glaring deal-breaker, but what about Picasso? Dederer dedicates an entire chapter to his abuse of young women. Should I pass by his paintings in every art museum I visit from now on? Or should I try to reinterpret his work through a new lens? Dederer’s argument leaves me with the troubling thought that I can justify the consumption of any art—despite the stain its artist’s biography places on it—as long as I find it meaningful.

Eventually Dederer goes further. “The initial thought of how to take responsibility is to boycott the art—the liberal solution of simply removing one’s money and one’s attention. But does that really make a difference?” Not in our current economic system, Dederer argues, which functions by shifting problems to the consumer. Liberal individualism strips us of our collective power, she asserts, giving us “a grandiose yet ultimately meaningless sense of the importance of our purchases, our gestures, our decisions.” Capitalism moves our focus from “the perpetrator and the systems that support the perpetrator to the individual consumer,” so we fail to see the larger structures that allow monstrousness to continue.

Given this reality, it doesn’t make sense to believe that an individual’s choice about whether to pay for a Kanye song can reshape the moral landscape that surrounds us. Dederer concludes: “We are left with feelings. We are left with love. Our love for the art, a love that illuminates and magnifies our world. We love whether we want to or not—just as the stain happens, whether we want it to or not.” She continues: “There is not some correct answer. You are not responsible for finding it.”

I put down the book and blinked once or twice, feeling unsatisfied with Dederer’s conclusion. She doesn’t offer a list of acceptable crimes that preserve the palatability of an artist’s work. Readers are left with no tangible answer to the fan’s dilemma, no real sense of comfort.

Perhaps that’s Dederer’s point. She writes, “The way you consume art doesn’t make you a bad person, or a good one. You’ll have to find some other way to accomplish that.” We can’t, as individuals, solve the systems of oppression that profit problematic artists. But we can try to notice them. Along the way, we can make choices about the art we consume based on what feels right to us. As Dederer says, we still have our feelings and our love.

And, I might add, our hatred.

* * * * * *

The Century's community engagement editor Jon Mathieu engages Ginger Monroe in conversation about her review.