A pastor’s disappointments

Amy Butler’s memoir is a story of relentless striving and continued failures. In other words, it’s a story of the church.

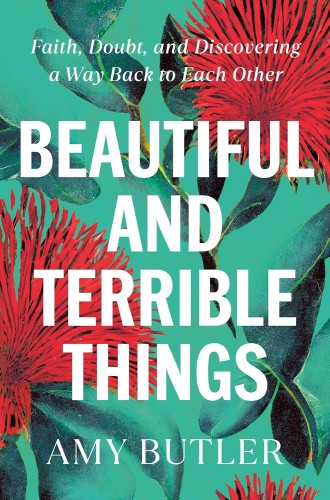

Beautiful and Terrible Things

Faith, Doubt, and Discovering a Way Back to Each Other

Of all the eponymous terrible things in Amy Butler’s memoir, the one that left the strongest impression on me was not the tragic death of a teenager in the streets of New Orleans, the nonviable pregnancy and late-term abortion, the childhood sexual abuse, the divorce, or the author’s tortuous departure from Riverside Church in New York City. It was the last words Butler, then an ordained Baptist pastor for ten years, ever heard from her staunchly conservative evangelical grandfather. “When I approached his chair and kissed him hello, he grabbed my hand and pulled me close, looked me straight in the eyes, and said: ‘You are the biggest disappointment of my life.’”

That dreadful imprecation, and the early life of relentless striving it discounted with such harsh finality, rang in my ears for the rest of the book. Beautiful and Terrible Things touches on several recurring themes in its episodic recounting of an upbringing in the evangelical world and an adult career in the Protestant mainline, especially the redemptive role of relationships and dialogue in a season of cultural polarization and institutional breakdown. But in the end, I think, it is a book about disappointment: in family, in churches, sometimes even in God.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

After a childhood marked by fundamentalist perfectionism, Butler pursues ministry education in a Southern Baptist setting that won’t accept women’s gifts for ordained ministry. (She recalls her male fellow interns at a big church being brought onstage and licensed to preach on the spot, while she is merely thanked.) Moving into Baptist circles that welcome women’s leadership, at least in principle, she discovers that even these congregations house sexism and ordinary cruel, petty behavior. When Butler and her husband divorce, she is surprised by how little unwelcome commentary follows. (That was its own terrible moment for me, to see someone surprised by a supportive response from a church.)

Eventually, Butler is hired by New York’s literally and figuratively storied Riverside Church, occupying the tallest church building in America, graced by preaching luminaries like Harry Emerson Fosdick and William Sloane Coffin and famed for a history of social activism. Due to what she describes with necessary vagueness as conflicts with lay leaders over a number of issues, including the chronic sexual harassment of staff and others by one of those leaders, her five-year contract is not renewed and she is forced to brass her way through a last Sunday at which she is forbidden from even mentioning her imminent departure.

Along the way, there are redemptive moments of human connection. Butler discovers the good-heartedness and cooperative impulses buried under facades of trivial criticism. She makes friends with a hard-line gun rights advocate after making public comments on gun control. She gets a huge Black Lives Matter banner hoisted on her Washington, DC, church building in time for the January 6 protest and riot, and she has a respectful interaction with one of its attendees. “When I get home, I’m going to tell my wife I met a woman pastor!” the man tells her. “If we find ourselves at a shore from which love has not built a bridge, perhaps here is where we teach one another to swim,” she concludes.

Through the course of her story, Butler’s faith changes, though perhaps not as much as the distance from hard-line fundamentalism to Riverside Church might suggest. Beautiful and Terrible Things is not the witness of one who has overcome a demanding and punitive childhood fundamentalism by discovering a gospel of grace; rather, it’s the story of inverting that fundamentalism into a more progressive dimension. Success—the accomplishment of some biblically inspired norm of personal and collective behavior—is still the criterion by which Butler seems to judge both herself and her communities, even if the meaning of success has changed. She tells a moving and revealing story about her biracial daughter responding differently to a Black school counselor telling her, “You are a light,” than to Butler telling her, “You have a lot of potential.” She uses the same word for Riverside: “If the tallest church in America could live up to all of its potential, just think about how encouraging and affirming that would be for other communities struggling with the burdens of institutional religion, conflict, and scarcity.” But it didn’t, and it can’t, because just like individuals, communities are something infinitely more, and other, than their “potential.”

This need for churches to be better, more activist, and more charitable with each other and the world than they are capable of being is fuel for disappointment, just as surely as the need for personal purity, single-minded piety, and familial tranquility. And this inevitable disappointment is reflected in the book’s end-stage Protestant ecclesiology, in which the church is not the body of Christ, not Luther’s “creature of the Word,” nor even, as the Second Vatican Council put it, the “people of God.” Instead it is an “institution,” merely “another vehicle by which some of us might encounter the Divine.”

This sets up the modestly hopeful conclusion to Beautiful and Terrible Things, in which Butler helps develop a fund for turning liquidated church assets into seed money for various spiritually inflected social enterprises. Old church buildings can be turned into coffee shops and art galleries that serve “as meeting spaces for spiritual community.” This may feel like a worthy legacy or even a step forward from the rickety, failed “institutional church.” But after 20 years, every social justice food truck or bakery will have either disappeared or become an institution itself, with its own regulations, conflicts, rules whose origins are forgotten, and niches for misconduct. Institutions are just what relationships look like over time. To endure—in a faith, in a vocation, in a form of community life—is also to disappoint.