A pulpit without a context

I asked ChatGPT for a sermon. What it wrote seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere.

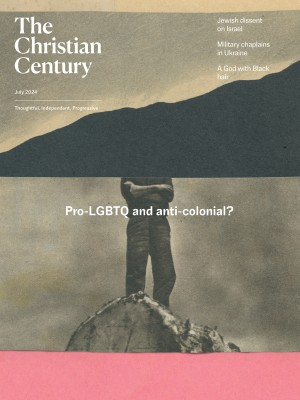

(Century illustration)

The cursor zips across the screen in the video introducing me to AI sermon tech. I watch as a preacher selects a quote from a list and then adds a “social starter” to the page. The sermon manuscript buzzes to completion, followed by offers for related products—creative engagement questions or “viral captions” for social media. The ad is fast-paced and shiny, conveying the promise of the product: to create sermons with greater impact in a fraction of the time.

Ads for AI sermon assistance appear unbidden in my inbox every couple of weeks. One company reminds me of the difficulty of the preaching task, how sermon preparation exacts hours from the preacher’s workweek. No doubt they are familiar with the adage, attributed to John Stott, that each minute of preaching requires an hour of preparation.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

These entrepreneurs have noticed that pastors are busy. Who has time to devote 20 to 30 hours a week to sermon preparation? The offers to fix my time crunch are tantalizing. One website offers “preaching freedom,” while another promises to help me rake back my “most limited resource: time.” Another AI tool will let me “spend more time focusing on other aspects of ministry.” I will produce dynamic, thought-provoking, empowering, turbocharged messages and I will do it quickly, outsourcing the research and the outline to my computer.

I brushed these offers away until recently, when I heard an interview with AI researcher and entrepreneur Dario Amodei. With crackling excitement, he described the exponential growth of AI capabilities. Surreal futures that we imagine to be decades away are likely to befall us in two or three years. Our daily lives will be suffused with AI. Maybe it is time for me to think more seriously about this sermon tech.

I started with an experiment. What could ChatGPT, the large language chatbot from OpenAI, do with a prompt to write a sermon about the post-resurrection appearance in Luke, the one where Jesus eats broiled fish with the disciples (24:36–43)? I gave ChatGPT an additional clue—that the sermon should be about doubt.

The results were mixed. The sentences contained more words than the average listener can process. The phrasing was formal and impersonal. Even a well-placed story couldn’t fix the cadence of the script. But the message, while bland, was accurate. Doubt is a part of faith and a universal experience. Doubt can lead the way to deeper trust and a closer relationship to God.

When I clicked “enter,” ChatGPT had sifted through a vast amount of sermons, articles, and more. The results (and my satisfaction with them) are affected by several factors. A large language model may begin with biased data; it may “hallucinate” or make things up. But I was unnerved that I couldn’t tell how ChatGPT decided what to write. Was this an aggregate of the most popular results, the most preached points on doubt? The sermons with the most clicks? Maybe a different criterion that I couldn’t guess?

Other ethical questions nagged at me. Several websites boasted that their products required no citations or acknowledgments. But whose ideas were these? Where did they come from? What kinds of communities and people were formed through these sermons? The AI sermon came from everywhere and nowhere simultaneously.

Last year, artist Kelly McKernan filed a lawsuit against two AI image generators. She’d noticed her distinctive style reproduced with increasing accuracy as users put her name into the generators. Her attorney described the results as “an infringing, derivative work.” I was certain other people’s sermons were infringed upon in the ChatGPT sermon staring at me from my Word doc, but I also wondered what was lost in the repurposing, in the cumulative anonymity of the text before me.

Preaching is solitary but not lonely. In each preacher exists a world of conversations, a genealogy of participants that span ages, the faithful who wondered and worked at the same text we wrestle with today. The Sunday after my AI experiment, I preached my own sermon about Jesus’ appearance to the disciples on the day of his resurrection, how he invited them to touch his side, to hold his body—he is alive! Later, I reread the manuscript to trace the faithful witnesses who made their way onto the page through me.

I could see the influence of Barbara Brown Taylor, who preached a sermon in which she imagined different scenarios for a gospel story to heighten the difference between our expectation and the outcome of the text. I’d done that, too. I’d also talked about “defenseless faith,” language that recalls Martyrs Mirror and reflects my Anabaptist theology. My style of engagement revealed the hours I’d spent listening to Vashti Murphy McKenzie effortlessly connect with congregations in her sermons. A recent discussion of the Luke passage with a precocious girl in my congregation helped me turn the text in a new direction.

I carried all of them with me into the pulpit that Sunday. I recognized a sensation I didn’t feel after reading the AI sermon. I was flooded with gratitude.

I wrote my sermon during a good week, one when I made space to stretch out with the text before me over days. That isn’t always the case. Other weeks I am crushed by emails, programs, and crises. I eke out what I can in the precious hours available. Some weeks I stare at a text that refuses to speak to me even as the hours tick down ominously toward Sunday morning. Instead of turning to AI generators, I’ve tucked away a word from Tom Long, who reminds me that not all of us are blessed with extraordinary preaching abilities just as most of us do not live off a continuous plating of five-star meals. “Instead,” he writes, “what truly sustains is daily bread—food lovingly, ably, and carefully prepared.”

My sermons may not be turbocharged, but they feed the people I love. Their ingredients are grown in a garden tilled by listening and learning from others as I’ve read and discerned the Bible with them. I gather these ordinary fruits from ordinary trees, and somehow, with a power and hope that exceeds my own abilities, I stir and savor, wait and watch, as raw elements become food.

Maybe one day AI will offer me tools that can assist in making ordinary meals of sermons, but not yet.