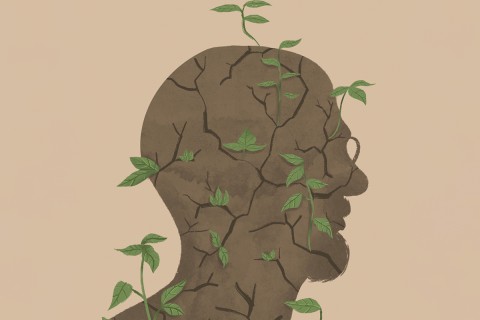

The roots of my deconstruction

The cracks in my faith came slow, like when plants grow under concrete.

The first crack that began the deconstruction of my faith came in the Old Testament class I took my freshman year of college. The professor was giving a lecture on Exodus (my favorite book) and the Israelites’ crossing of the Red Sea. “Oh, by the way,” he said in passing, “the Red Sea is probably better interpreted as ‘Sea of Reeds’ and wasn’t really a sea as we imagine it, simply a vast marsh that perhaps dried miraculously with a strong wind.”

I sat in class with my ears ringing. I could feel the splintering. So much of who I believed God to be rested on that passage, on that miracle. The only thing I could do was push back. Clearly this man isn’t Christian. This school isn’t even Christian. I dropped the class. The answer was clear. I had to transfer to a real Christian college. In truth, it was also the homesickness and the grief of losing my father the year before. If God was going to hold all these pieces together, I thought, then I’d need to protect him.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The next crack came my sophomore year, when I met an amazing woman—and told her that women can’t be pastors (her mom was a pastor) and that speaking in tongues isn’t real (she was Pentecostal). But she was harder to accuse and impossible to leave. Her stories of her mother and her prayer life seeped into my readings of Acts and Ruth and Paul. The women’s names seemed to press off the page and become texture under my fingers, their presence a current in the whole arc of God’s movement in the world.

These cracks didn’t come quickly, like a hammer shattering a terra-cotta pot. It was more like a root winding its way under a slab of cement and then simply growing—its slow, steady growth inevitable unless I was going to keep hacking away at the vines beneath the surface.

In the months and years that followed, the roots continued to creep. As a junior, I read and argued with Kelly Brown Douglas’s The Black Christ, and I was challenged as well by my African American history class. More cracks developed in the context of the Black student union at Duke Divinity School and the Fund for Theological Education’s doctoral fellowship program. These were webs of moments and people and histories that left the sidewalk slabs of my faith lifted and split, barely fit for walking.

My faith no longer looked like a safe, segmented path that kept me from the dangers of the road. When I heard the cracks, there was fear, a sense of loss. But even as the splits began to form, there was never pure absence, nothingness, or even wreckage. I hadn’t been struck by a hammer or a bulldozer, some inanimate object built to break or take apart or strip away and then leave the building for something that came along later.

Instead, each crack that formed came from a deposit, a presence that was growing. I was striking out at people who I thought wanted to take my faith apart. But in truth, I was encountering people whose faith differed from mine, people who had questions about their faith and out of their walk with God asked those questions. In some ways it was the hardness of my own conservative faith that led to the cracks. Had there been more room for questions, perhaps the impact wouldn’t have felt so violent.

I’ve heard many people lament that their journey of deconstruction has left them more just but less joyful. But can there be any joy when we have to overlook what’s in our midst—or even try to kill it—in order for the certainty to remain? I suppose this is the danger of deconstruction, that nebulous space between what was and will be. But I wonder if deconstruction is always the right word, if it inevitably leaves us looking for a different set of rules and certainties.

Maybe instead of deconstructing we simply need to let the wild things grow. We let go of a faith that is neat rows of wheat, a faith that is neighborhood subdivisions and sidewalks that keep us on a tidy loop. Maybe when we demystify our faith we can see the life that’s growing under the concrete we’ve so carefully poured. We can see faith in the questions as much as in the answers, and we might begin to trace the roots to a different tree—a different space of joy that grows beyond the fences and does not ask us to cut off our doubt or fear or someone else’s description of God.

Under every crack there is something that’s growing, something that’s been planted in us. For everything we thought true that is proven historical or contextual or just plain made up, there’s also a presence—a person who says, “I hope that the world does not have to be this way.” Otherwise, why ask the question?

Once enough cracks are there, the old will fall away, the scales will peel away. But maybe there isn’t absence. Maybe with each question something was also growing: a latticework roots, of histories, of communities believing that God is here and is more than what our words can capture.