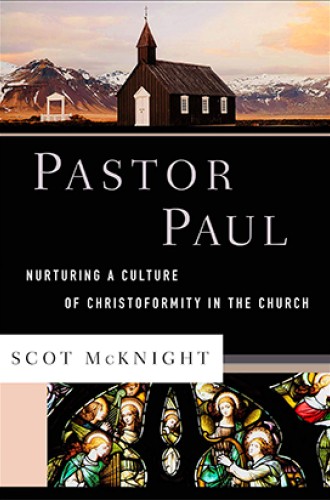

Shaping a place where people can become more like Christ

Scot McKnight looks to Paul to define the pastoral task.

In the best kind of way, this book makes me feel like I’ve not been much of a pastor. I sit in my clerical collar, in my church office, alongside several bookshelves filled with many books about the church and ministry. Very pastor-like. But have I been pastoring? If these sorts of things—or even the fact that I preach more than 40 Sundays a year—don’t assure me that I am pastoring, what does?

Scot McKnight sees a model for pastoral ministry on display throughout Paul’s letters, and he suggests that Paul’s ministry centers on one essential task: Christoformation, that is, forming a culture in which people can be conformed to Christ. Across Paul’s letters, McKnight sees a concerted effort to nurture a culture in which such conformity can take place.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This, then, is what assures me that I am pastoring, at least in a Pauline key. Pastors are pastoring when their work is geared toward nurturing and tending a culture of Christoformity. It’s the kind of work that Jason Byassee and Matt Miofsky describe as “forging a crowd into a church.”

This isn’t only the pastor’s work, of course. The leadership, the congregation, their relationships, and the policies that govern them all converge into a culture. The pastor or leadership team, however, are called (or sent) to throw their energy into shaping a culture in which Christians grow in Christlikeness. As McKnight puts it, “pastors don’t create Christoformity—that’s done by God in Christ through the Spirit. But they are called to nurture it, to plant and to water and to weed and to protect and to provide.”

What kind of culture is needed for Christoformation? Through the glimpses of Paul’s own pastoral work found in his letters, McKnight focuses on seven examples of how he sees Paul nurturing a culture of Christoformity. I find two of these particularly provocative: one expected, and the other unexpected.

A culture within which someone is conformed to Christ, McKnight says, is marked by friendship. He winsomely outlines historical definitions and implications of friendship before mapping the significance of friendship in Paul. He shows how Paul’s practice of friendship reworks classical Greek conceptions, especially using the language of covenant. McKnight employs the word rugged to describe the commitment of covenantal friendship ad nauseam, but it fits because Paul’s vision of friendship anticipates the need for endurance in the heavy work of becoming Christians.

One of the ways Paul reconceives friendship is to do away with the idea of friendship as something had only by males and elites. Instead, Paul befriends all sorts of people in what Douglas Campbell sometimes refers to as “strange friendships.” Friendships among clergy and within congregations, McKnight says, are essential “portals into the church culture.” A culture devoid of friendship cannot nurture Christoformity.

Another characteristic of cultures that nurture Christoformity, this one less obvious, is what McKnight calls “world subversion.” In a climate where churches wring their hands over relevance, they can become quite concerned with maintaining a worldly enough image to not frighten potential attendees. The work of evangelism turns into marketing, analytics for success transform beloved friends into numbers, and so on. A pastor who is guided by nurturing Christoformation, McKnight says, will see these things for what they are.

Reflecting on Paul’s subversion of the Corinthian church’s worldliness, McKnight suggests that “the pastor’s responsibility is to perceive where worldliness lurks in our churches and to subvert it with nothing less than the cross of Christ.” What I love about Paul’s tactics of world subversion, as McKnight describes them, is that they are as shrewd as a serpent but carried out with dove-like innocence. He quotes Eugene Peterson: “If I’m not willing to help [the congregation] become what they want to be, what am I doing taking their pay? I am being subversive. I am undermining the kingdom of self and establishing the kingdom of God.” A culture in which people can grow in Christlikeness is one that subverts the false worlds that vie for our allegiance.

I was surprised that McKnight didn’t offer a sustained reflection upon one particular Pauline practice that was meant specifically to repudiate worldliness and conform people to Christ: communion. Paul’s corrective of the Corinthians’ misguided practice of the Lord’s Supper would seem to fit right at the heart of McKnight’s thesis. Paul portrays communion as a place where we practice fellowship with Christ and one another in such a way that the reality of our identity with and in Christ is most embraced and so formed. As I read this book, I found myself asking: How might a culture of participation in Christ through communion nurture Christoformity?

I’ve heard Will Willimon say you shouldn’t become a pastor just because you like people. That’s good advice. You also shouldn’t become a pastor just because you’re good at organizational leadership, fundraising, or public speaking. You should become a pastor only if you sense God calling you to join the slow work of the Trinity transforming people through love into Christlikeness. Your clerical collar, your bookshelves, your office, and your sermons may help. Liking people, leadership skills, and fundraising may help, too. But this book will put to death any notion that those things are enough.

If you’re like me, this death might hurt a little. But McKnight also gives us reason to take heart: these things must be put to death in order that our pastoral ministry might be raised to life with Christ. And a ministry with Christ will surely nurture a culture of Christoformity in the churches entrusted to our care.