Thinking about Good Friday during a pandemic

This year the Solemn Reproaches are speaking to me in a new way.

I was walking through the narthex to my church office one Good Friday morning when I heard a tenor voice singing in the sanctuary: “O my people, O my church, what more could I have done for you? / Answer me.”

I cracked open the door and slipped into the back pew. Our cantor, Dan, was standing by the font. He glanced my way and kept chanting: “I gave you a royal scepter, but you gave me a crown of thorns; / I gave you the kingdom and crowned you with eternal life, / but you have prepared a cross for your Savior.”

Dan was rehearsing the Solemn Reproaches, which he would be leading at that evening’s service. This ninth-century liturgical text gained popularity over the years and was eventually added to the Western church’s liturgy for Holy Week. The Solemn Reproaches are often used on Good Friday as a companion to the Adoration of the Cross.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

A reproach expresses deep hurt or blame, and such a statement can be used for good or for ill. In the Solemn Reproaches, Jesus addresses people who have harmed him—and the text has a long history of stirring up violence against Jewish people. Many times over the centuries, in many places, Christians bowed before the cross on Good Friday and heard or sang some version of these words: “I led thee through the wilderness 40 years, fed thee with manna, and brought thee into a land exceeding good, and thou hast prepared a cross for thy Savior.” Then they’d leave the church, form a mob, and attack Jewish communities.

Evangelical Lutheran Worship, the 2006 worship book used in my denomination, includes a new version of the Solemn Reproaches that seeks to undermine this anti-Semitic legacy. It adds New Testament imagery and words like church to clarify who it is that Jesus is reproaching. It also adds a stanza that explicitly condemns this history of misplaced blame: “O my people, O my church, what more could I have done for you? / Answer me. / I grafted you into my people Israel, / but you made them scapegoats for your own guilt, / and you have prepared a cross for your Savior.”

I sat in the back pew listening to Dan sing, and after a few minutes I began to join in on the Trisagion, sung after each stanza of the Solemn Reproaches as a congregational response: “Holy God, holy and mighty, holy and immortal, have mercy on us.” We sang together for a while, starting again from the beginning when we’d reached the last stanza. We didn’t say anything to each other; we just kept singing, back and forth across an empty church, alternating between Christ’s reproaches to us and our pleading calls for God’s mercy.

I think about the Solemn Reproaches a lot these days. A virus that looks like a crown of thorns is multiplying uncontrollably, and our collective anxiety about it has left us alternating between language of reproach and language of pleading.

The pleas have been fairly straightforward, even as they’ve increased in urgency and intensity: Wash your hands. Stay home if you’re sick. Don’t hoard face masks. Cancel all large gatherings. Pass legislation that guarantees paid sick leave. Shut down schools. The reproaches have been more complicated, as we’ve struggled to understand the causes of the pandemic. I’ve heard people blame globalization, secretive governments, unequal access to health care, an unregulated market that made it easy for a virus to jump across the animal-human barrier, the narcissism and denial of world leaders, people who don’t cough into their elbows, climate change, delayed test kits, cruise ships, handshakes, pangolins, political appointments motivated by loyalty instead of competence, overcrowded prisons and detention centers, open work spaces, communion by intinction, and asymptomatic carriers.

Reproaches can be useful—particularly if we direct them toward ourselves, naming our sins and striving to correct our errors as we move forward. But as resources become scarce and panic increases, it can be easy for our reproaches instead to turn outward and morph into violence—whether that means overtly xenophobic mob actions or just the cumulative harm caused by millions of small decisions made out of anxiety.

Christians have responded to past pandemics in a variety of ways. In February 1349, with the plague looming, the municipal authorities of Strasbourg in Alsace rounded up the city’s Jewish people, accused them of poisoning the Christians’ wells, demanded that they convert on the spot, and burned about 1,000 of them alive.

But it’s also true that in the third century, when a plague nearly wiped out the Roman Empire, Christians became known for performing unsolicited acts of compassion and self-sacrifice. Cyprian, who was the bishop of Carthage at the time, wrote these words:

How pertinent, how necessary, that pestilence and plague which seems horrible and deadly, searches out the righteousness of each one, and examines the minds of the human race, to see whether they who are in health tend the sick; whether relations affectionately love their kindred; whether masters pity their languishing servants; whether physicians do not forsake the beseeching patients; whether the fierce suppress their violence. . . . These are trainings for us, not deaths: they give the mind the glory of fortitude; by contempt of death they prepare for the crown.

Being forced to envision our own mortality can strip us bare of all pretenses and reveal who we really are.

That Good Friday morning when Dan and I rehearsed the Solemn Reproaches in the empty church, a complex beauty emerged. The sanctuary, built in a midcentury architectural style that I can only describe as urban stark, was already stripped of all adornment. Everything soft—paraments, linens, cushioned kneelers, flowers, candles, books—had been removed during the Maundy Thursday service the night before. In that somber space, Dan’s voice and mine resonated only with stone, bricks, concrete, and wood.

It was a rehearsal, but it was as real as any act of worship ever is. There were only two of us, and yet we were confessing the sins of all Christians across the centuries. The heaviness of our guilt—as individuals, and as the body of Christ in a world marred with violence and inequity—was palpable. The need for God’s mercy felt thick.

But just as thick was the presumption that God would indeed grant that mercy. We knew even as we were pleading for it that it was already ours. We remembered that we were singing to a God who had jumped across the divine-human barrier in order to be able to bleed and sweat and catch viruses and weep and ache and die. That’s why Dan and I kept singing, hesitant to stop.

But it was Good Friday, and we worked at a church. We had a lot to do. Before too long, we went back to our offices so we could complete all of the Holy Week tasks that still needed to be done.

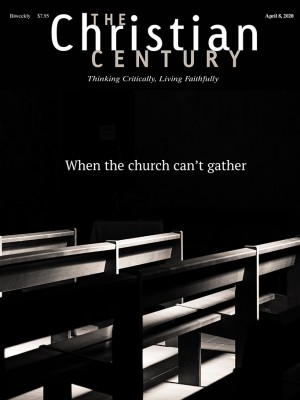

This year, many churches may be empty on Good Friday because of the pandemic. But I’d like to think that the chanting of prior generations will resonate even in those stark, still sanctuaries: “Holy God, holy and glorious, holy and immortal, have mercy on us.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Reproach and pleading.”