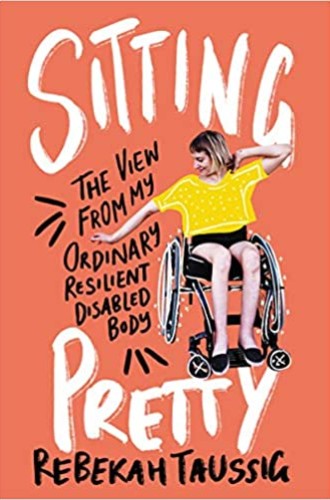

The view from Rebekah Taussig’s wheelchair

Sitting Pretty showed me how much I have to learn about ableism.

Several of my parishioners have experienced life in a wheelchair. Whenever I think of one of them, Cindy, I remember seeing her at our annual bazaar, speeding in the breeze from one booth to another so quickly that her ponytail stuck almost straight out, a huge smile on her face. Contrast that with Rebekah Taussig’s description of a 2016 photoshoot in which Kylie Jenner posed using a wheelchair: “Jenner’s image depicts disability as purely passive, as if her wheelchair is her cage, when in real life, wheelchairs are empowering, liberating tools for so many people.” While many assume that a person in a wheelchair would rather live differently, Taussig says a dream of being separated from her wheelchair is her recurring nightmare.

Sitting Pretty is a memoir in essays, with each chapter focused on a theme such as romance, work, or feminism. Taussig, whose Instagram platform (@sitting_pretty) has more than 40,000 followers, has credentials beyond personal experience: she has a PhD in creative nonfiction and disability studies. But she never sounds like a preachy academic. I did find her copious parenthetical asides to the reader distracting at first. Eventually, though, her winsome conversational tone drew me in, and I saw her fascinating perspective flourish.

One chapter describes her experience teaching about disability to a group of high school seniors. She explains to them the difference between a medical model of disability, which focuses on the disability as a problem to be addressed, and a social model, which shifts the focus to the experience and context of disability and the settings that lead to disabling moments for the person with a disability. Her students resist illumination, which frustrates Taussig. But her account of her persistent attempts to enlighten them creates an enriching educational experience for the reader.

Taussig writes compellingly about going through contortions to keep from alienating people with ableist presumptions. She notices that tendency in another woman’s Reddit thread about not having had a romantic relationship in 18 years of using a wheelchair. Taussig writes, “The impossible, relentless task of making other people feel comfortable with our disabilities—of helping them see us as human without making them feel threatened or shamed—is stunningly familiar.” About a year after Taussig moved in with her boyfriend, their neighbor, after seeing them holding hands and kissing, asked whether they were brother and sister. He was surprised to learn they were romantically involved, apparently because of Taussig’s disability. She posits, “Instead of disability as the limitation, what if a lack of imagination was the actual barrier?”

In a chapter called “Feminist Pool Party,” Taussig struggles with not wanting to challenge White feminism with yet another intersectionality. The need was glaring, however, when she attended a panel featuring young women successful in their various professions. The panel was diverse in terms of ethnicity and class but did not include a woman with a disability. When an audience member asked a question about work-life balance, the panelists all responded with nervous laughter, saying they hadn’t achieved such balance. Taussig thought at the time, “Really? Is that it? Let’s all just giggle about the impossibility of having both a career and a body with limits?” She goes on:

Literally and truly—every single woman is subject to the demands, uncertainties, and limitations of her body—a body that strains under the forces of gravity and time, that wrinkles and breaks, swells and sags, accumulates pain and injury. . . . When we pretend disability is not a part of womanhood—when we keep the two separate and distinct—we’re all left less equipped, less adaptable for the inevitable challenges of life.

As a lung and breast cancer patient, I especially resonated with Taussig’s chapter on the complications of kindness. She writes, “As a veteran Kindness Magnet, I’ve found people’s attempts to Be Kind can be anything from healing to humiliating, helpful to traumatic.” This chapter offers several scenes from her life as examples, such as the time when she was grading papers in a busy coffee shop and a young woman interrupted her because she believed that God wanted her to pray for Taussig to walk.

Taussig offers illustrations that are not personal as well, such as the internet genre of popular high schoolers taking students with disabilities to prom. Such stories may make us feel hopeful, but are they actually helpful? Taussig wants to reexamine such gestures. “Thoughtful reactions take time and reflection,” she writes. “What does the person in front of you actually need?”

Another YouTube genre of which I was unaware features paralyzed brides and grooms walking painstakingly down the aisle at their wedding. Taussig insisted on walking down the aisle at her first wedding, requiring laborious, sweaty preparation, and ultimately leading to a detached, out-of-body experience rather than a tale of triumph. She points out that while we may be stirred watching a paralyzed person meticulously making their way down the aisle, “other stories are being reinforced here, too,” such as seeing “mobility aids [as] sad symbols of defeat and disease.”

My church claims inclusion as one of its core values, and I have been pleased by our ramps, accessible restrooms, and chairs that ushers can easily remove so that people in wheelchairs can sit wherever they like in the nave. Sitting Pretty showed me that these few things have resulted in complacency and that, as with racism, I still have much to learn about ableism and a lot of work to do. In addition to raising consciousness, this book has something to say to everyone about our own bodies and their limits. Taussig’s tone is never scolding. She emphasizes imagination: How could we do this differently? How can we expand our ideas of inclusivity?