Abram without Sarai (Genesis 12:1–4a; John 3:1–17)

What we know about Sarai is what she lacks. This week’s reading lacks her.

To receive these posts by email each Monday, sign up.

For more commentary on this week's readings, see the Reflections on the Lectionary page. For full-text access to all articles, subscribe to the Century.

The Holy One summons Abram. This provides a crucial puzzle piece for the backstory of the Hebrew Bible.

Abram teaches us about how our ancestors in faith viewed the Holy: as one who calls, even from afar; as one who blesses the called; as one who stands with the called and either with or against others, depending on their relationship to the called; as one who blesses with the intent of spreading that blessing to “all the families of the earth.”

Abram goes when called, despite the great distance. That is a good amount to establish in three and a half verses, and much of it informs contemporary Christian ideals about the Holy One. As God summoned Abram, so God summoned the Greco-Roman followers of Jesus (John 3:11–17), and so God summons us yet today.

Within this brief passage, two groups hide in plain sight: women and Indigenous peoples. A longer reading from this passage, Genesis 12:1–9, will appear later this year. There we will meet Sarai, Abram’s wife, who is also included in the genealogical material in Gen 11:29–31. In 11:30 we learn that “Sarai was barren; she had no child,” which sets up one of many barriers to fulfillment of God’s promises as we work through Genesis 12–50.

What we know about Sarai is what she lacks. This week’s reading lacks her.

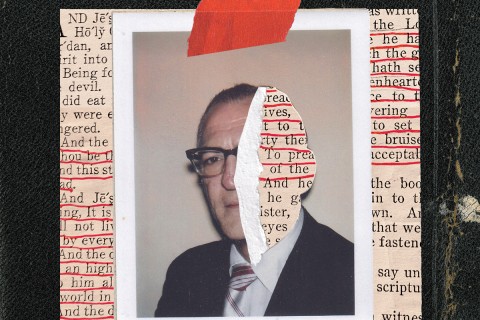

When we continue reading beyond 12:4, we encounter a baffling story. During a visit to Egypt to escape famine, Abram says that Sarai is his sister for fear that the Egyptians would kill him in order to acquire her (12:10–20). Instead, he just gives her to them, offering her up as a sexual plaything of Pharaoh, even receiving quite a nice payment for her. Though Abram asks her to play along with his ruse, we never hear Sarai’s voice in this story.

Notably, this passage never appears in the Revised Common Lectionary, and neither do the two other echoes of the so-called “wife-sister” story in Genesis 20 and 26:1–11. (Perhaps this explains why few if any of my students have ever heard of it when we study it in class!) That our ancestors in faith would have retained this story in three similar versions suggests that it held great importance to them. Who are we to eliminate it all three times?

These wife-sister stories beg to be remembered in worship settings. While I can certainly sympathize with the difficulty of preaching this story, it nonetheless teaches some truths; a MeToo generation can find plenty to work with here. We still have not run out of callous and cowardly patriarchs who will find “their” women dispensable for the sake of their own protection. There’s plenty to ponder about both justice and mercy in a story where God works through even these men, even when they must learn the same lesson repeatedly, and in sequential generations! This should give pause to the rest of us humans, who also tend to grapple with selfishness and fear.

These stories also teach about a God who pays attention to the matriarchs, having been passed off as sisters in a fit of patriarchal paranoia. The women deserved better protection from the deity, or at least from those who told their stories. The least we can do is retell and reflect on those stories, and to take them as a call to pay better attention to the matriarchs in our own time.

This short lectionary excerpt also overlooks the peoples of the land of Canaan. We read in 12:6 that “at that time the Canaanites were in the land.” This invites curiosity. Who were they? What became of them?

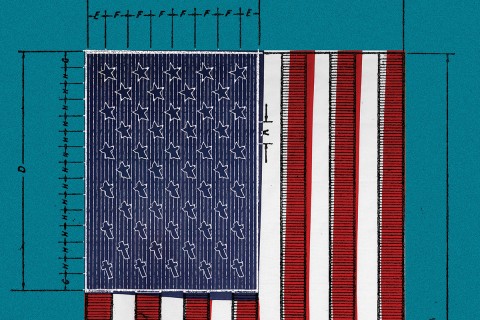

Archaeologists offer us the insight that, in all probability, the ancient Israelites had originally been Canaanites. Robert Warrior’s classic article “Canaanites, Cowboys, and Indians” pushes us further to consider the implications of this promise of land to our more recent faith ancestors, based on how it has been used throughout history—particularly in the drive to acquire North American land through the displacement and killing of its Indigenous peoples. After being exposed to Warrior’s critique, we should never read “Canaanite” the same way again.